Inflatable Saxophones, Novelty Fedoras, and the Allure of Plastic Party Favors

They’re big business at bar and bat mitzvahs and other celebrations. But why do we want them?

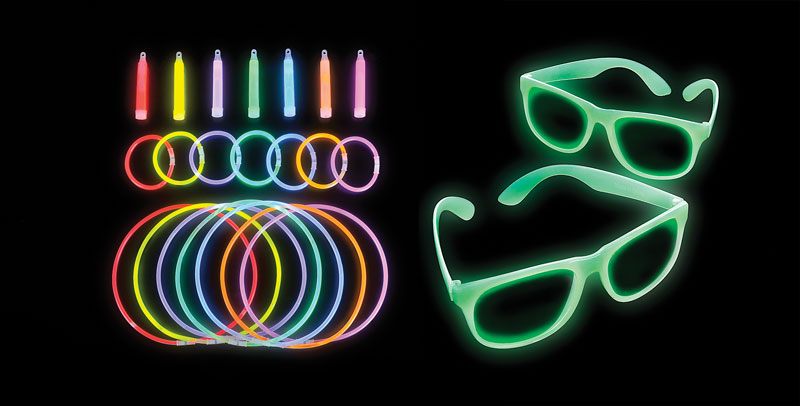

For years in my preteens, jewel-toned maracas, dead glow necklaces, sombreros, and an array of plastic Blues Brothers–style sunglasses were strewn on the floor of my basement in the suburbs of Boston. Stuck in an infinite loop of getting tossed away and then replaced the following weekend, the bar and bat mitzvah party favors that took up residence among a lifetime’s worth of random detritus were reminders of the hours spent in synagogue social halls, dancing to “Cotton-Eye Joe,” and running back and forth on the dance floor in a free pair of ankle socks as a DJ barked orders.

Giveaways—specifically, the generic, ordered-in-bulk, usually plastic kind—are as much of a bar/bat mitzvah party tradition as the candle-lighting ceremony and the “Cha Cha Slide.” While wedding guests around the world have been receiving various mementos for centuries, bar/bat mitzvah attendees had to wait until the late 1980s before they too got a tangible, albeit useless, reward for showing up. Still, even after nearly 30 years, kids and adults continue to clamor for a stack of glow necklaces and an inflatable saxophone, knowing full well that their loot will get thrown in the trash and dumped in a landfill by the end of the week.

But where did they come from, when will they go, why do we want them, Cotton-Eye Joe?

“In general [conspicuous consumption at bar/bat mitzvahs] is a coastal phenomenon,” says Jeffrey K. Salkin, the author of Putting God on the Guest List and senior rabbi at Temple Solel in Hollywood, Florida. “In California, the notion is you have to be famous, and in New York, the notion is you have to be famous and rich,” he says.

According to Rabbi Salkin, after World War II, American Jews were eager to showcase their newly acquired affluence, turning to bar and bat mitzvahs as a forum to display their upper-middle-class status. “One can say that this happens in every generation—as soon as a generation gets money, they want to demonstrate it,” Salkin says. And what better way to flaunt a “money’s no object” attitude than by dropping hundreds of dollars on enough tchotchkes to fill an Olympic-sized ball pit?

Even before party favors became mainstream in the late 1980s—the ETA given by Rabbi Salkin as well as the other DJs and sales reps I spoke with—the lavish bar/bat mitzvah party was already the subject of national interest and facing criticism. On April 29, 1963, the article “Jewish Leader Criticizes Bar Mitzvah ‘Vulgarization’” was tucked snugly among other city news on page 23 of The New York Times, featuring Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs president Philip Goldstein calling the increasingly extravagant celebrations “‘a form of social climbing’ with ‘mounting ostentation verging on bad taste.’” Another article, “Who Is Harvey Cohen and Why Is Everybody Saying Such Wonderful Things About Him?” from a 1978 issue of People magazine, included a quote from a rabbi who said that the Cohen family’s party, which cost upwards of $19,000 and was held at the 80,000 seat Orange Bowl in Hollywood, Florida, was “‘more bar than mitzvah.’”

According to the Encyclopedia of American Industries, total party favor sales rake in approximately $360 million per year, but the category’s standing as a niche facet of the Gift, Novelty, and Souvenir Stores industry, which itself is a subcategory of the Miscellaneous subsector of the Retail industry, means that official statistics don’t dive too deep. While representatives from Oriental Trading Co. declined to comment, those from Rhode Island Novelty, Windy City Novelties, and even the Plastics Industry Association explain that giveaways are equally popular at school dances, corporate fundraisers, and other major milestone events, which means that no one’s keeping track of how many janky tambourines are handed out during the hora.

Mike Schrimmer, the founder and owner of Windy City Novelties, is probably the closest thing there is to a party favors thought leader. In the 1970s, Schrimmer invented the glow necklace after cutting open a 6” glow stick and then connecting it to the airline tube from his brother’s aquarium. Once he realized that he could connect both ends to make the straw into a necklace, he took his invention to Buckingham Fountain in Chicago, where he sold 400 at $3 a piece on the first night out.

“I sat at the fountain and made hundreds of necklaces during the day, waiting for the night crowds of tourists lured by the awesome night light show at the fountain,” he explains. However, “I was arrested the second night for vending without a city permit, which was not offered on that property.”

Five years later, he opened Windy City Novelties, first only selling glow necklaces before expanding its merchandise to include 18,000 other illuminated party goods, such as glowing shot glasses and footballs. “We have sold hundreds of millions of necklaces around the world,” he says.

Debbie Dragon, a sales representative to DJs and event planners at Windy City, says that while the original favors, such as Blues Brothers glasses, plastic fedoras, and maracas, have maintained their popularity, LED products, such as light-up rings, bracelets, and wands, are becoming a mainstay.

Phil Cohen, founder of the Boston-based DJ company Cohen Productions, echoed the growing appeal of LED goods, adding that these days, ultraviolet black lights are all the rage. Still, he’s been doing this long enough to know that at the end of the night, most of what he gives out will be quickly forgotten. “They’re fun at the time,” he says. “But if someone goes to a sporting event and they get one of those foam hands that they hold up, they’re not going to bring it home and reuse it at the next game.”

While Cohen and other DJs I spoke with noticed a decline in excessive giveaways, none of them foresee their overall extinction. They do tell reluctant parents that party favors aren’t a requirement, but, according to New York-based DJ David Swirsky, “most parents get them even though they are not excited to.”

As for why, that depends on who you ask.

Kristina Shampanier, along with Dan Ariely and Nina Mazer, researched how low prices and free giveaways impact consumers’ decision-making. Their paper, Zero as a Special Price: The True Value of Free Products, argues that the perceived benefits of a product are higher when it’s free than when it’s for sale.

“Free products elicit an unexpectedly high positive affect from consumers,” writes Shampanier in an email. “This affective reaction makes consumers chose these products even when standard economic theory would predict that other choices are better for them. Thus, it is not surprising that people will avail themselves of free glow sticks or plastic hats at parties even if they know that those choices are not ‘rational’ (e.g., not ideal for future storage space situation or for environment).”

But for Rabbi Salkin, it boils down to a face-off between religion and capitalism.

“I think it came from a growing American sense of specialness,” explains Rabbi Salkin. “Upper-middle-class people have to be special so they have to cling to materialistic things that give them the sense that they have made it, and that they are important, and that their child is really important.” He also says, “[a glow stick] represents something that people can take away from the experience, that they will remember it by. Apparently it’s no longer sufficient for people to have nice memories of being at a bar mitzvah. They now have to have souvenirs. It’s just American materialism expressed on a new level.”

But in the eyes of Michael Nowack from Rhode Island Novelty, it’s not that complicated. “It’s pretty simple,” he says. “It’s impulse stuff. People like giveaway stuff. It’s just a part of what we do.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook