Marie Curie As You’ve Never Met Her Before

The world’s first two-time Nobel Laureate was a nerd’s nerd who broke the law for knowledge.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

Trailblazing physicist and chemist Marie Curie constantly defied societal expectations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—even breaking a few laws along the way. Born in Russian-controlled Warsaw on November 7, 1867, she was fiercely proud of her Polish identity. She spoke, read, and taught Polish—despite that doing so was illegal and could mean getting shipped off to Siberia. At the time, Russian authorities banned women from attending university, but that didn’t stop Curie. After earning her Ph.D. in Paris, she became the first person, male or female, to receive two Nobel prizes, first in 1903 for physics and then in 1911 for chemistry. “In a time when simply being Polish, female, and educated was an act of defiance,” writes mathematician and author Katie Spalding, “she made her name specifically, and proudly, as all three.”

Spalding’s new book, Edison’s Ghosts: The Untold Weirdness of History’s Greatest Geniuses, uncovers a rarely explored side of Curie. Alongside other historical geniuses, Spalding delves into the quirks of Curie, from attending a clandestine university to using a glowing chunk of radium as a nightlight (leading, in part, to her radiation exposure-related death at 66). In doing so, Spalding offers up a far more human picture of the revered brainiac. Atlas Obscura spoke with Spalding about Curie’s political activism, the secret “Flying University” she attended, and the power of insufferable women.

What was Marie Curie’s early life like?

At the time, Poland wasn’t recognized as a country. So Marie was born in a Russian province. Modern-day Poland was split between Russia, Germany, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And the Russians were basically doing everything they could to stamp out Polish culture. They took out Poland from the title of the province. Kids were banned from speaking Polish. They weren’t taught any Polish literature or history. Marie remembered how her teachers would spy on her and her friends at school: If they were overheard speaking Polish, then they would be punished.

Before she was born, her parents were both really successful teachers. But because they were pro-Polish, they had a lot of job opportunities taken away. So by the time Marie was growing up, they were dirt poor and had to rent out rooms in their house.

What was the Flying University? How did Marie end up attending it?

Under Russian rule, women were only allowed to attend primary school. Marie’s brother was allowed to go to university but she wasn’t, which is why she joined the Flying University. It was this clandestine university that didn’t officially exist and moved from place to place so that the Russian authorities couldn’t find it. It was set up by people with pro-Polish sentiments in Warsaw. You had to be told where the classes would be. They taught banned things like Polish literature, Polish history, Catholicism. They even had a secret library. She not only got an education there that she couldn’t legally get, but she also taught other women there.

Imagine being such a nerd that you would illegally go to university. It’s one of the coolest things that I’ve ever heard of because I too am the kind of nerd who would go to university illegally.

How did Marie end up moving to Paris?

Marie and her sister, Bronya [Bronisława], hatched this plan that once they were old enough, they were going to go to Paris to study, where women were allowed to [do so]. Bronya would go first while Marie stayed at home and earned [money] to support Bronya, and then once Bronya had finished, they would swap and Marie would go.

What was life like in Paris for Marie?

Marie had to redo a few years of university. It’s kind of hard to be like, “Hey, can I do a degree, please? My alma mater doesn’t exist technically.” She actually did two degrees at once in physics and math because she was what you might call an overachiever. She was again dirt poor. She would go hungry a lot. She would not have heating; she would just wear layers and layers and layers. She did all of her experiments in an old leaky shed behind the university buildings. But she seemed to have really loved Paris anyway.

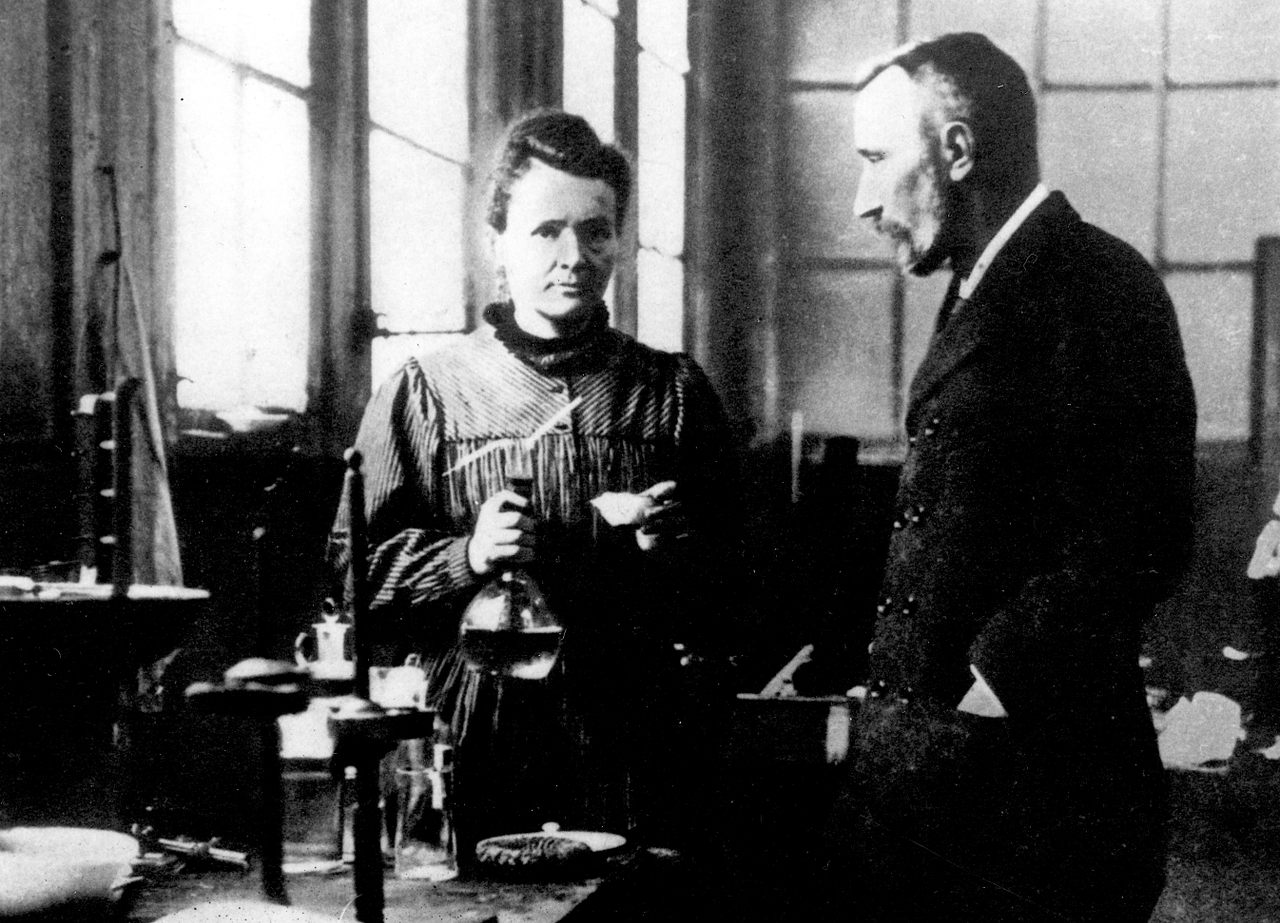

How did Marie meet her husband, Pierre Curie?

He was working at the university as a teacher, and she evidently was fed up with working in a leaky shed and one of their friends introduced the two saying, “She needs a lab. You have a lab. How about you two team up?” They basically fell in love while they were both working in the lab being massive nerds.

What was their relationship like?

She got so much crap for being a woman in science and throughout all of it he just had her back. She was almost passed over for her first Nobel prize because everyone assumed, “Well, she’s the woman. She was probably adjacent to the discovery.” And he got wind of it and was the one who said, “No, you have to give her the Nobel Prize. She’s the one that discovered it.”

What are some of the surprising things Marie and Pierre did in the name of science?

Marie kept a massive lump of radium as a night light. She used to say, “Oh this radium gives off such a lovely, beautiful little light, so I keep it right next to my bed every night.” Pierre strapped a vial of radioactive material to his arm and they both just watched it burn his skin. They constantly just walked around holding radioactive material. Pierre used to wander around with lumps of it in his pocket just in case he ran into someone who might be interested in seeing some. Marie would spend whole days stirring cauldrons full of boiling uranium.

There is a good argument to be made that they can’t have known any better. But I would also argue that if you have discovered something which is warm and glowing and literally burns your skin off as you watch, then maybe don’t hold it against your skin for 10 hours. I can’t imagine that two intelligent people could look at that and think there is nothing to worry about.

What would it have been like to hang out with Marie?

I think it would have been very cool to be her friend and go drinking with her. I think if you weren’t her friend, you would have really hated her. I think she would have been one of those people where you talk to her and you’re like, “Oh my God, everything’s a manifesto.” Because, as a woman in science, she would’ve had to be that way. She seems to have had absolutely no chill whatsoever. She was a massive workaholic. She got married in her lab dress and I’m pretty sure she just went back to work afterward. Whenever someone was like, “Oh, Pierre made that massive discovery the other week.” She was like, “Actually I made the discovery; he had nothing to do with it.”

Especially if you were a man at the time, I bet you’d think she was insufferable. Not that I have a problem with that. I think there should be far more insufferable women out there. I probably am one myself.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook