A Cultural Historian Explores an Old Mental Hospital, and Why They Scare Us

They are haunted, but not by ghosts.

Rising 200 feet out of the hills of rural West Virginia, a clock tower looms over a vast and empty collection of buildings that once housed thousands of people diagnosed with mental illness. After being shuttered for more than 20 years, since 2007 the Weston State Hospital has been open for business again under its original name—the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum—and caters to tourists interested in some combination of history and the paranormal. Some buildings are off-limits and most of the site is without electricity, but a considerable portion of it awaits the curious and the brave. As I pulled in to the vast, park-like grounds, the imposing, cut-stone main building leered in the late afternoon sun. The architecture is Gothic-inspired, and the windows dark—like it was made to evoke a sense of dread and mystery. But this is precisely not what the builders wanted to inspire.

I’m an academic historian of American culture at Southern Connecticut State University, and my trip to the Trans-Allegheny began years earlier, when I saw it featured late one night on a ghost-hunter television show. What was it that made this place so scary? Was it always that way? (According to the Travel Channel, the hospital is one of the 10 most haunted spots in the country.) I spent the next five years tracking the dark narrative of mental hospitals through fiction, memoir, film, media, and art. I watched hundreds of movies, read scores of novels, and pored over heaps of periodicals. Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that Americans have always been deeply invested in what goes on within the walls of these institutions, and I began to understand why. The term “asylum” itself, which has negative connotations today, was originally used to evoke confidence, safety, and security. How and why this changed is part of this longer story of stigma, fear, and horror. A “ghost tour” through the Trans-Allegheny is the logical end of the story. Or perhaps, more precisely, the opening of another chapter.

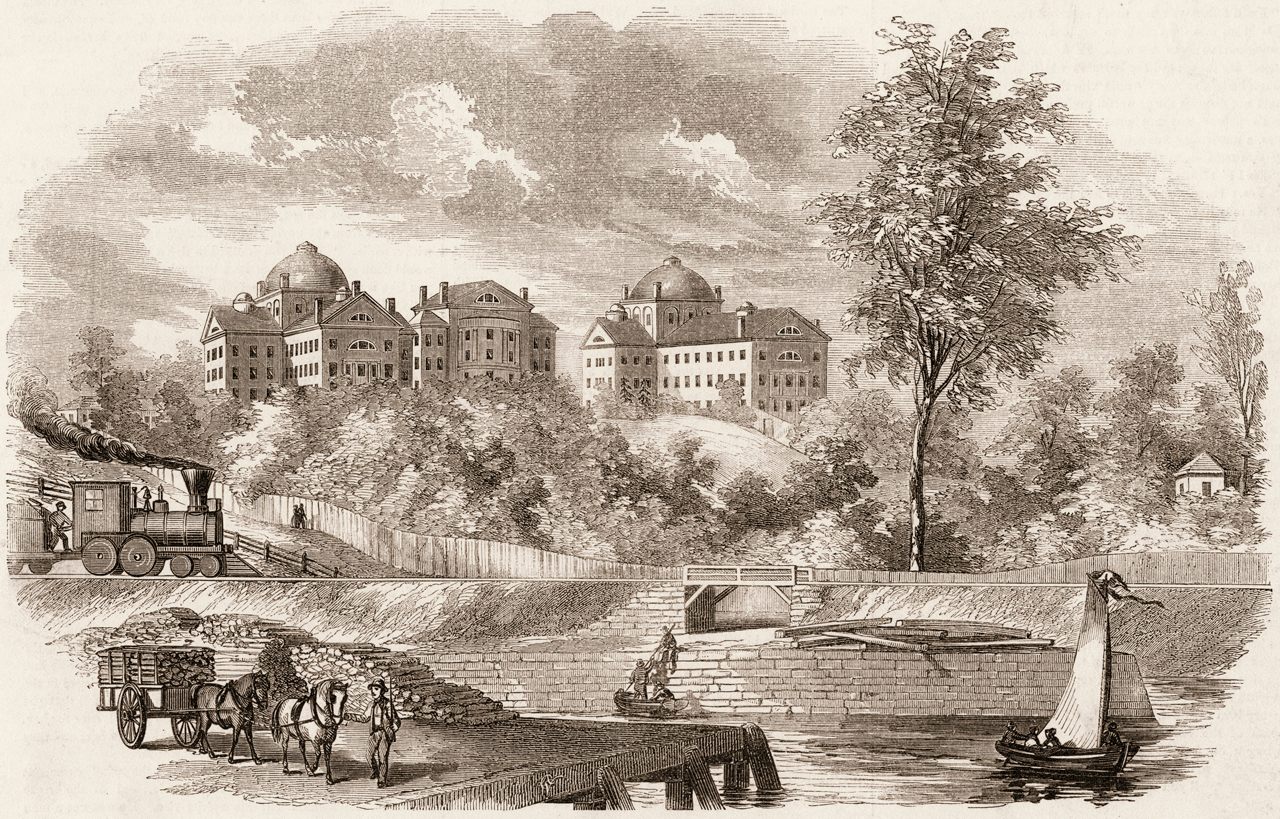

The Trans-Allegheny was once among the most expensive buildings in the United States. Ground broke on this massive collection of sandstone buildings in 1858, with the forced work of incarcerated African-American laborers, and continued on and off through the 1950s. Situated on over 300 acres, it was designed to evoke optimism and the spirit of reform that gave birth to similar mental hospitals around the country, beginning in the 1830s.

These public works were sold as monuments to healing, mansion-like and airy, with cutting-edge medical treatments and scientific architecture. Inside, a person committed there was said to encounter occupational therapy, medication, hydrotherapy, even hypnotherapy. Superintendents boasted that the older methods—chaining up the “mad” in basements—had been abolished. Straitjackets and strong rooms, it was said, would be used only sparingly. Clean air, baths, simple food, and healthful activities were considered cures for disorders of the mind, and the reported “cure” rates were—at least at first—terrific.

These “asylums”—the word in common use at the time—were meant to feel like a refuge, but were also products of a very different understanding of mental illness. As such, they also employed high doses of opium, bleeding, harsh purgatives, and devices such as the “Utica Crib” and the “phrenological hat.” Still, the institutions were not operated as though they had something to hide. Tourists were encouraged to visit, and postcards and even patient newspapers were printed for public consumption. In 1842, Charles Dickens called on a number of mental facilities during his American tour. He was famously unimpressed by Blackwell’s Island Asylum in New York, but found the Connecticut Retreat for the Insane in Hartford “admirably conducted” and the Boston Lunatic Asylum to be a place embodying “enlightened principles of conciliation and kindness.”

But even in those years, exposés, novels, and short stories began to cast America’s asylums as mysterious, even sinister. In 1833, one Robert Fuller called the McLean Asylum for the Insane in Massachusetts a “tyrannical Institution” and a “dungeon.” Isaac Hunt’s 1851 description of the Maine Insane Hospital told of a “most iniquitous, villainous system of inhumanity, that would more than match the bloodiest, darkest days of the Inquisition or the tragedies of the Bastille …” Pioneering feminist Mary Wollstonecraft locked her protagonist up in an asylum for her controversial 1798 novel Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman. Edgar Allan Poe set a dark comedy, “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether,” at the fictional Maison de Santé hospital, where the protagonist encounters a mad doctor who lords over a topsy-turvy world ruled by the patients.

Without a firm understanding of the causes of mental illness, or more advanced pharmaceutical or therapeutic options, these places were never going to achieve their goal of humane treatment of mental illness—a goal we still grapple with today. By the end of the 19th century, the hospitals were clearly overwhelmed. Stays grew longer, treatments were revealed as ineffective, and conditions worsened markedly. And thanks to a widely copied 1890 New York state law that made the state wholly responsible for the care of people with serious mental illness, patients kept flooding in. Overworked doctors tried dangerous new drugs and treatments, or simply neglected their charges. Things were even worse in the segregated, “colored” hospitals for African Americans, which typically had much lower budgets and fewer treatment options. In an effort to reverse the bad publicity, superintendents started renaming their institutions “hospitals.” It made little difference.

The demise of these big state hospitals began in the late 1960s, spurred by the widespread availability of thorazine (called the “chemical lobotomy”), a new Medicaid provision that funneled federal mental health funds to nursing homes, and a new emphasis on outpatient care. Deinstitutionalization of mental illness emptied many struggling hospitals, but also put many former patients, damaged by their institutional quarantine, on the streets and in prison.

This larger historical arc is mirrored, beat for beat, in the history of the Trans-Allegheny. Inspired, like many of the large state hospitals, by physician-reformer Thomas Story Kirkbride, it was designed for “moral treatment.” Kirkbride’s animating idea was that space, air, and rest would cure most cases of mental illness, hence the wings were set back in a staggered pattern to facilitate maximum light and air into each ward, and the grounds were planned with pleasant walkways, lawns, and fish ponds. Renamed the West Virginia Hospital for the Insane by the new state government of West Virginia in 1863, it welcomed its first batch of 20 patients in fall 1864. By 1881, the massive clock tower and the fourth wing of the main structure were completed, at significant cost to the state. It was touted as the largest hand-cut stone building in America.

The hospital was designed for 250 patients, but by the end of the century there were nearly 500 in residence. Intake diagnoses included “hereditary,” “epilepsy,” “menstrual,” and “masturbation.” By that time the cure rate was reported as 26 percent, much lower than earlier levels. Another name change, to Weston State Hospital in 1915, reflected a lack of confidence in the operation of the hospital, and within a couple of decades, the patient population was more than 2,000. New treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy and lobotomies, were introduced. The crowding increased and conditions further declined.

By the time the hospital closed, at the tail end of nationwide deinstitutionalization, in 1994, it had lived through the lifecycle of just about every American mental hospital: early optimism, local boosterism, poor results, declining conditions, overcrowding, and finally desperation and closure. As with other hospitals, Weston shut its doors after years of diminishing support and patient numbers.

The grand old abandoned asylums carry the weight of a heavy past. Many are Kirkbride structures: massive faces, extended bat-like wings, tall ceilings, and extensive facilities. Cupolas and towers top many of them, which look castle-like. Nature has reclaimed many of the forgotten ones, which makes them alluring and hazardous. Hydrotherapy tubs, ventilation pipes, broken toilets, empty bed frames, and rotting dance floors: The mental hospital has become core to the idea of “ruin porn.” And for good reason. These features that these sites are known for, frankly, have long been associated with hauntings in popular culture.

Some states have declared their abandoned hospitals strictly off-limits, citing health hazards, including asbestos. Some hospitals have been repurposed. Fairfield State in Newtown, Connecticut, for example, has recycled and updated some of the buildings for municipal functions, and added a large youth sports complex to the site. Others, such as Blackwell’s Island (on what is now called Roosevelt Island) combined demolition with extensive refurbishment to create luxurious private living and commercial spaces. And then there are the hospitals that have entered the paranormal tourist trade.

In 2007, a contractor purchased the derelict Weston building from the state at auction for $1.5 million. The new owners revived its original, more frightening, less socially acceptable name, and began a program of limited restoration and courting of audiences interested in history or that like a good scare. The employees at Trans-Allegheny report that the site, as an attraction, has been a great boon to a local economy, which calls to mind the civic optimism that came along with its construction in the 19th century.

I arrived at Trans-Allegheny in the afternoon, and my experience began with a historical tour led by a docent dressed as a nurse. She explained the history of the buildings in great detail and related the stories of some of the patients with sensitivity and a modern understanding of mental illness. We meandered through a section of the central building, including a small museum, medical facilities, and the parklike courtyard in the back. A few spaces, such as one well-appointed hallway section, have been renovated to their midcentury splendor, with period furniture, fresh paint, and carpeting. In other places peeling paint and grimy floors spoke to the fact that most of the building has been untouched since 1994, and in many cases much earlier.

But I had signed up for more than the history experience. I was to return that night for the “Ghost Hunt,” in which about 30 visitors were allowed to see much more of the hospital between 9 pm and 5 am. I arrived that evening with a thermos of Starbucks, some snacks, a notepad, a headlamp, and a Ghost Meter EMF sensor (purchased online for $39.95). I wanted to understand the place that the old asylums have taken in the modern American imagination.

The large group was broken up into teams of 10 or so, and each was led through tours of different floors within the massive central building and its attached wings. The guides related history and legend and then let us wander freely for an hour or so in each new area. Walking through such a dark space is disconcerting and disorienting by itself. With my headlamp on a subdued setting, I could make out objects and doors but little else until I got close up. There were many times that I found myself alone. The hallways were staggered, and opened onto bedrooms, offices, bathrooms. One section had a row of cells. Wheelchairs seemed to have been strategically placed. My EMF device remained quiet.

In one area, a guide told me about Big Jim, who, it is said, murdered another patient with a bedpost. Here was the process for contacting him. Sit in the dark room and unscrew the head of your flashlight until bulb and battery lead are just disconnected. Then ask Big Jim a question and wait to see if his spirit would make the connection to make the light flicker on. There was some flickering, which means that it was at least a very good story to tell your friends later. I returned there later, after the tour, and sat in the dark room across the hall, my headlamp off, curious if something would happen—some noise or creak or visual artifact of the kind that tends to inspire ghost stories.

There was nothing, but that didn’t make it any less terrifying.

As the night went on, I continued patrolling the dark halls, sometimes away from the group, and I heard the sounds and thought I saw things in the shadows (though nothing that couldn’t be explained a dozen ways by animals, architecture, and the psychology of the unknown). I entered rooms and sat as still as I could. I checked that ghost meter. If there was a sensation that stuck with me, it might be the smell of old cigarette smoke—a direct sensory connection with the departed residents, it seemed. I’m a scholar, a skeptic, someone who knows how, over the years, a drumbeat of movies, rumors, horror stories, and more have made the classic American state mental hospital into an object of terror—maybe the most haunted class of buildings in the country. I know all that. But it’s impossible not to be affected by this.

These abandoned hospitals still have a lot to teach us. And sometimes that’s what’s most scary about them. None of us visitors slept that night, but rather spent the whole time exploring. I left in the light of the morning, tired but glad that I had had the experience. I neither saw nor heard any evidence of the supernatural, but I recalled all the stories and films from my years of research and started to see them in a new way. We, as a society, created these horrors, in allowing the overcrowding and decline of places of healing, in the stigmatization of people with mental illness, in the mistreatment of even the staff. Something about spending the night in the facility let me trace this path of hope and despair for myself.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook