Giant Kangaroos Once Towered Over Humans at 8 Feet Tall

New studies from a boneyard of fossilized skeletons may reveal why the ‘roos grew and hopped the way they do.

A dried-up lake bed sits in the heart of the Australian Outback, more than 100 miles from the nearest road or settlement. Beneath its dusty surface, multiple fossilized skeletons have been lying here for thousands—even millions—of years. But though they’re very large, these old bones do not belong to dinosaurs. The remains have been resting in Lake Callabonna since at least the late Pleistocene epoch, and many of them belong to giant kangaroos that used to tower over humans.

It’s really three previously unknown types of ancient kangaroos that met their end here. The findings at Lake Callabonna cracked open a world of marsupial discovery over the past decade, launching one Aussie researcher on a mission to find out more. That researcher is Isaac Kerr, a kangaroo paleontologist at Flinders University and the lead author of a study just published in the journal Megataxa.

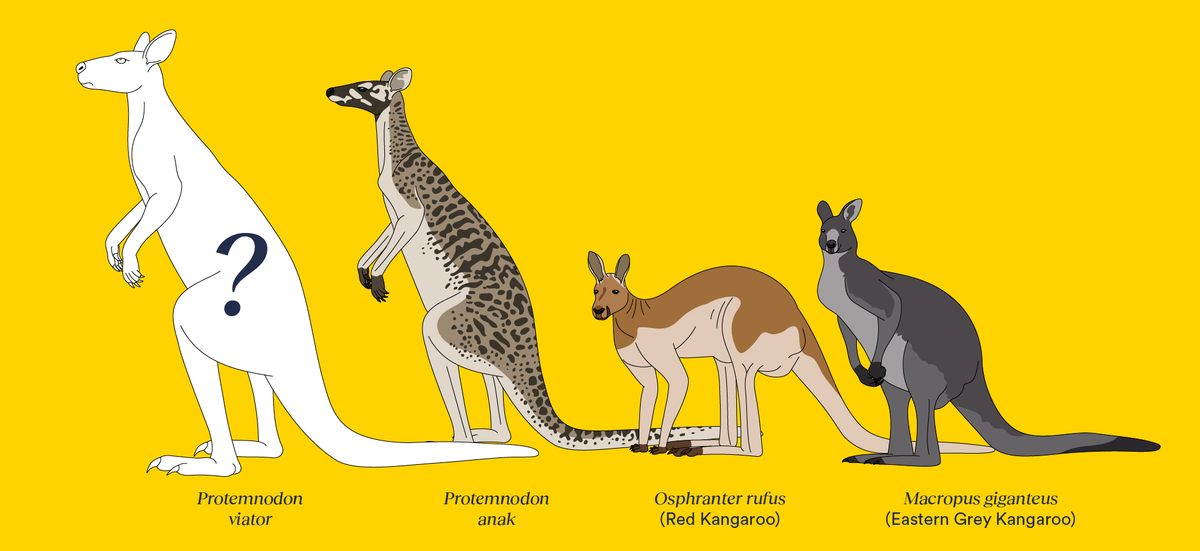

The study identifies three previously undescribed kangaroo species belonging to the extinct genus Protemnodon, aka a genus of really big ‘roos that lived 40,000 to 5 million years ago. The biggest described is the newly named Protemnodon viator, a true behemoth that would have been twice the size of even the beefiest buck living today.

Currently, Australia’s largest extant marsupial is the red kangaroo, which reaches about five feet when fully upright. P. viator would have stood at roughly six feet in a crouched position and eight feet tall if it were to stand up straight “in a threat posture,” Kerr says. But what’s even more astonishing is their estimated weight: about 375 pounds versus the average male red kangaroo of the present day, which weighs only up to 200 pounds.

P. viator would have looked sort of like a squat and muscular version of the grey kangaroo (though clearly much bigger), as would all other Protemnodon species. Including the three introduced by this latest study—P. viator, P. mamkurra, and P. dawsonae—the genus now contains a total of seven species. The genus was first raised 150 years ago by the Victorian-era British biologist Sir Richard Owen, the same guy who coined the term “dinosaur.”

As technology advanced and better fossils were found, Owen’s identification of the species under Protemnodon have been challenged and redescribed. Part of the reason for revisiting the research was the discovery of a megafaunal boneyard on Lake Callabonna in 2013. Kerr, who attended one of the subsequent expeditions to Callabonna while pursuing his pHd, describes the lake as “dry, very remote in northeastern South Australia, and littered with megafauna skeletons poking out of the clay and eroding away.” The dryness, he says, has a lot to do with why the ancient Protemnodon species were so large.

Starting about 10 million years ago, Australia experienced a period of aridification that would have peaked 17,000 to 2.3 million years ago (i.e., the Protemnodon period). As the country dried out, kangaroos evolved to be bigger. They also became faster, more efficient hoppers, Kerr says, “as they had greater distances to cover for food and water, and more room to move quickly and in a straight line.”

The fossils used for this study, found at Lake Callabonna as well as in the collections of 14 different museums in four countries, show varying hopping methods indicating a range of habitats across Protemnodon species. P. viator is named after the Latin word for “traveler,” because it had such a broad distribution, whereas P. dawsonae and P. mamkurra would have stuck to woodlands.

With such a wide range, it’s not unlikely that these giant kangaroos would have crossed paths with some of the First Australians, who Kerr says probably would have hunted them—or at least would’ve tried to. He says he hopes that this investigation into Protemnodon lifestyles will help us better understand how climate change has impacted Australian fauna in the past, and how it could impact it in the future. Next, he anticipates returning to Lake Callabonna later this year to collect specimens from the largest marsupial to ever live, the Diprotodon optatum, a giant wombat-like creature that’s now extinct, of which there are hundreds.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook