The Strange Case of Antarctica’s Red and Green Snow

It’s not a Christmas trick, but the colorful effect could change everything.

In Antarctica, global warming has been turning the snow green. And no, that’s not a good thing.

It’s all happening on and near the Antarctic Peninsula, the bit of the Frozen Continent that juts out furthest north. It’s one of the fastest-warming places on Earth. By some accounts, average annual temperatures have increased by almost 3°C (5.4°F) since the start of the Industrial Revolution (c. 1800).

The Peninsula is where, in 2020, Antarctica’s temperature topped 20°C (68°F) for the first time on record. On February 9, 2020, Brazilian scientists logged 20.75°C (69.35°F) at Seymour Island, near the Peninsula’s northern tip. Just three days earlier, the Argentinian research station at Esperanza, on the Peninsula itself, had measured 18.30°C (64.94°F), a new record for Antarctica’s mainland.

Those warmer temperatures are not without consequences. Certainly the most spectacular one are the giant icebergs the size of small countries that occasionally calve off from the local ice shelves (see #849). Less dramatically, they also led to an increase in microscopic algae that colored large swathes of snow green, both on the Peninsula itself and on neighboring islands.

These “snow algae” are sometimes also known as “watermelon snow,” because they can produce shades of pink, red, or green. The cause is a species of green algae that sometimes contains a secondary red pigment. Unlike other freshwater algae, it is cryophilic, which means that it thrives in near-freezing conditions.

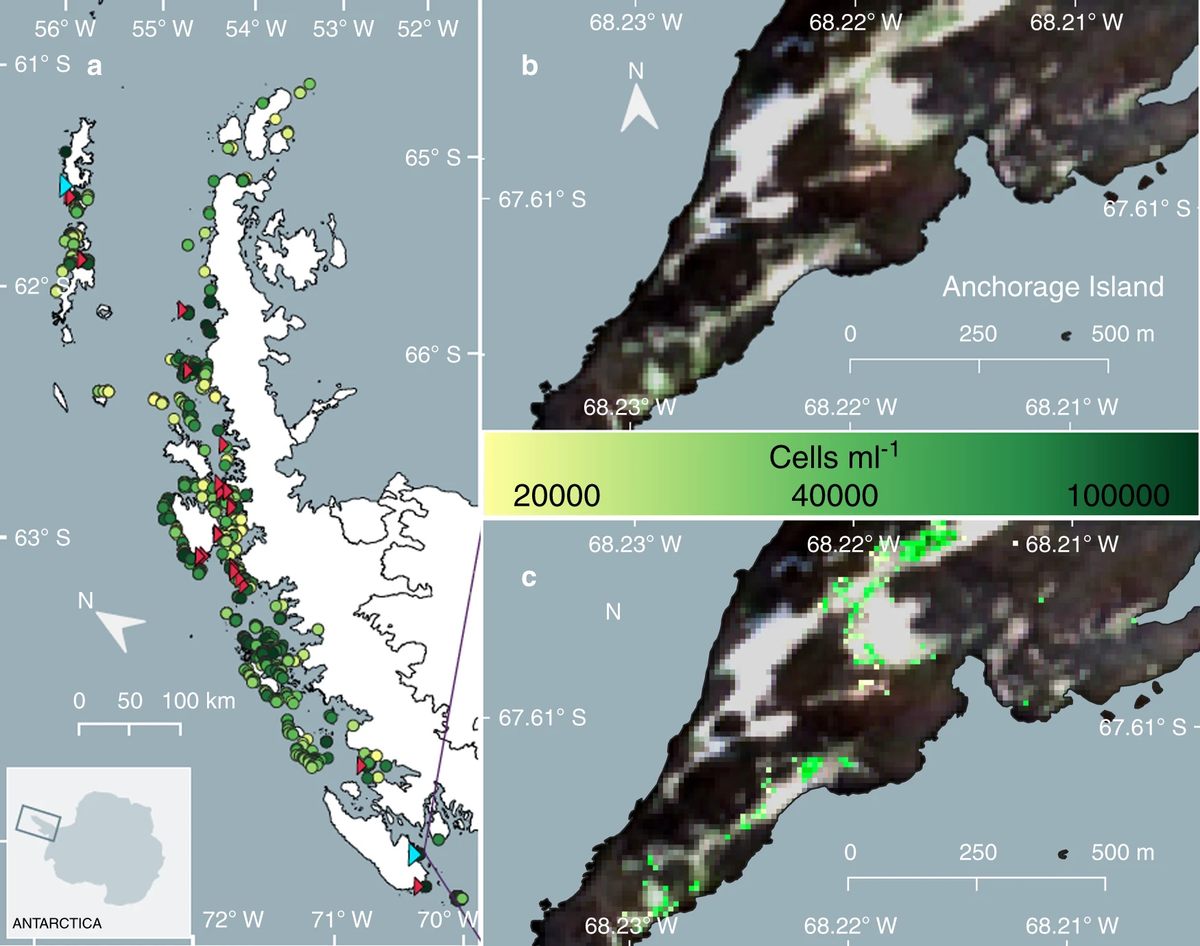

The first ever large-scale map of the Peninsula’s snow algae published in the journal Nature Communications in 2020. Single-cell organisms they may be, but they proliferate to such an extent that the patches of snow and ice they turn a vivid green can be observed from space.

The team who produced this map actually did use data from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel 2 constellation of satellites, adding field data collected on Adelaide Island (2017/18) and Fildes and King George Islands (2018/19).

Prepared over a six-year period by biologists from Cambridge University in collaboration with the British Antarctic Survey, the map identifies 1,679 separate “blooms” of the snow algae.

The largest bloom they found, on Robert Island in the South Shetland Islands, was 145,000 square meters (almost 36 acres). The total area covered by the green snow was 1.9 square kilometers (about 0.75 square miles). For comparison: Other vegetation on the entire peninsular area covers about 8.5 square kilometers (3.3 square miles).

For the algae to thrive, the conditions need to be just right: Water needs to be just above freezing point to give the snow the right degree of slushiness. And that’s been happening with increasing frequency on the Peninsula during the Antarctic summer, from November to February.

Like other plants, the green algae use photosynthesis to grow. This means they act as a carbon sink. The researchers estimate that the algae they observed remove about 479 tons of atmospheric CO2 per year. That equates to about 875,000 average UK car journeys, or 486 flights between London and New York.

That’s not counting the carbon stored by the red snow algae, which were not included in the study. The red algae are estimated to cover an area at least half of the green snow algae, and to be less dense.

About two-thirds of the algal blooms studied occurred on the area’s islands, which have been even more affected by regional temperature rises than the Peninsula itself.

The blooms also correlate to the local wildlife—in particular to their poop, which serves as fertilizer for the algae. Researchers found half of all blooms occurred within 100 meters (120 yards) of the sea, almost two-thirds were within 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) of a penguin colony. Others were near other birds’ nesting sites, and where seals come ashore.

This suggests that the excrement of the local marine fauna provides essential hotspots of fertilizer like nitrogen and phosphate, in what is otherwise a fairly barren environment. The researchers suggest the algae in their turn could become nutrients for other species, and thus be the building block for a whole new ecosystem on the Peninsula. There is some evidence the algae are already cohabiting with fungal spores and bacteria.

“Green snow” currently occurs from around 62.2° south (at Bellingshausen Station, on the South Shetland Islands) to 68.1° south (at San Martin Station, on Faure Island). As regional warming continues, the snow algae phenomenon is predicted to increase. Some of the islands where it now occurs may lose summer snow cover, thus becoming unsuitable for snow algae; but the algae are likely to spread to areas further south where they are as yet rare or absent.

The spread of snow algae itself will act as an accelerant for regional warming: While white snow reflects around 80% of the sun’s rays, green snow reflects only around 45%. This reduction of the albedo effect increases heat absorption, adding to the chance of the snow melting.

If no effort is made to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, scientists predict global melting of snow and ice reserves could push up sea levels by up to 1.1 meter (3.6 feet) by the end of the century. If global warming continues unabated and Antarctica’s vast stores of snow and ice—about 70% of the world’s fresh water—were all to melt, sea levels could rise by up to 60 meters (almost 200 feet).

That may be many centuries away. Meanwhile, the snow algae map will help monitor the speed at which Antarctica is turning green by serving as a baseline for the impact of climate change on the Earth’s southernmost continent.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook