Reading American History Through Handkerchiefs

There’s more to them than meets your nose.

In a collection that’s been growing for decades, Ann Mahony has what she estimates are over 5,000 vintage handkerchiefs, depicting everything from nursery rhymes to leisure pursuits, such as skiing and golfing. Most of her cloths are from the U.S. and range from 70 to 100 years old. However, collecting hankies is more than just a personal hobby for Mahony. She is a handkerchief historian and a member of the Textile Arts Council at San Francisco’s de Young Museum. It’s her job to interpret the story arc depicted on these fabrics.

What most people consider a charmingly antiquated sneeze-catching accessory can also showcase sociocultural history. Hankies, she says, offer a “perfect reflection” of what concerned and entertained people at the time a particular pattern was produced. “Handkerchiefs tell the tenor of the time, the mood of the country, what people were thinking and focused on,” she says. In other words, there’s more to handkerchiefs than meets your nose.

Handkerchiefs show up in world history as early as the first century BC, when they were mentioned by the poet Catullus and used for utilitarian purposes, such as wiping one’s brow or general-purpose cleaning. They would not become fashion accessories until at least the 17th century.

At early Greek and Roman athletic games, seas of spectators frantically waved white cloths, some of which were likely sudariums, a neckerchief worn by Roman military officers. Handkerchiefs occupy a key role in Shakespeare’s Othello and in textile history. In the Elizabethan era, hankies were high-end gifts, which nobles were known to present at New Year’s to the royal court. And in the 1840s, they were so ubiquitous among certain classes that the French novelist Honoré de Balzac wrote of his desire to unravel and demystify the female psyche based on “how [women] hold their handkerchiefs.”

By the turn of the 20th century, hankies were a necessary part of city life, as urbanites would breathe through the cloth to combat the smell and toxicity of air pollution. Presidential campaigns produced commemorative hankies, and handkerchiefs became popular wedding favors and special event keepsakes. As the handkerchief historian Helen Gustafson put it, from around 1800 until the early 20th century, handkerchiefs were ubiquitous. “Everyone everywhere [had] them,” writes Gustafson.

Thanks to increased industrial production and the widespread use of colorfast dyes that do not run or fade, an affordable, beautiful consumer handkerchief heyday emerged in the United States in the first half of the 20th century. During the Great Depression, no one was splurging on new clothes, but a single hankie, brightly adorned with embroidery or a graphic print? Mahony says that type of affordable accessory was still within reach for even working-class women.

In the 1930s, floral, polka dot, and other bold patterns emerged. Geometric prints became popular during the 1940s. Even puppy prints followed the popular breeds of the day. When Zsa Zsa Gabor and Elizabeth Taylor favored poodles in the 1950s, so did handkerchief designers keen to keep up with the times.

During the mid-20th century, handkerchief design took a decidedly modern turn. With the Great Depression and World War II in the sociocultural rearview, consumers were looking for new diversions. Mahony notes that trends toward suburbanization and leisure pursuits during this era made their imprint on handkerchief design.

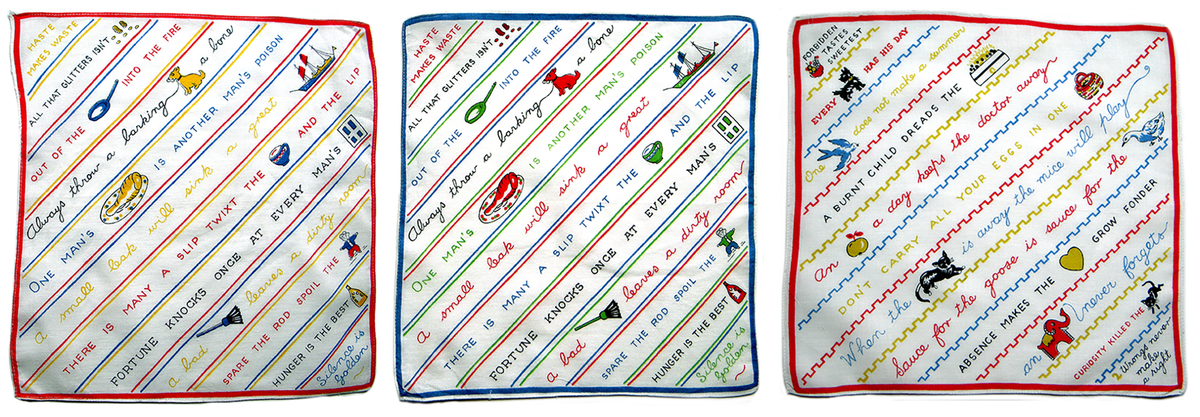

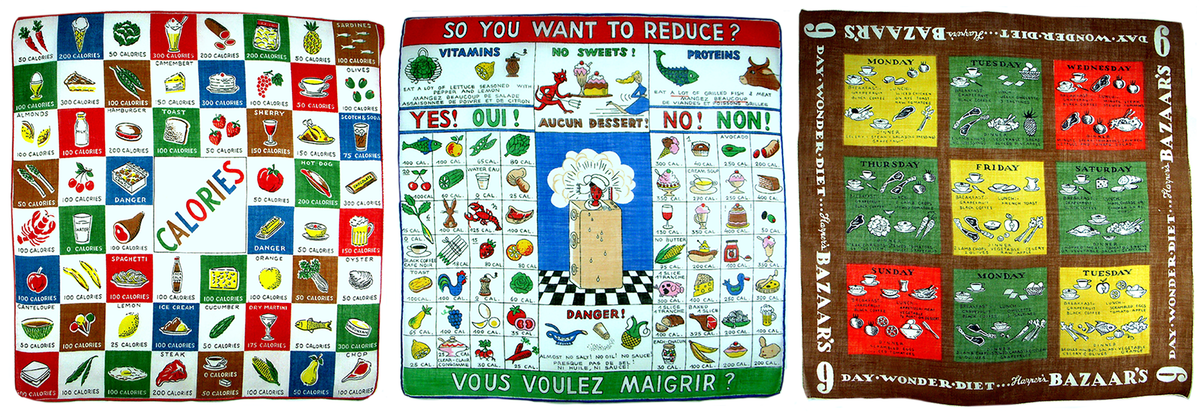

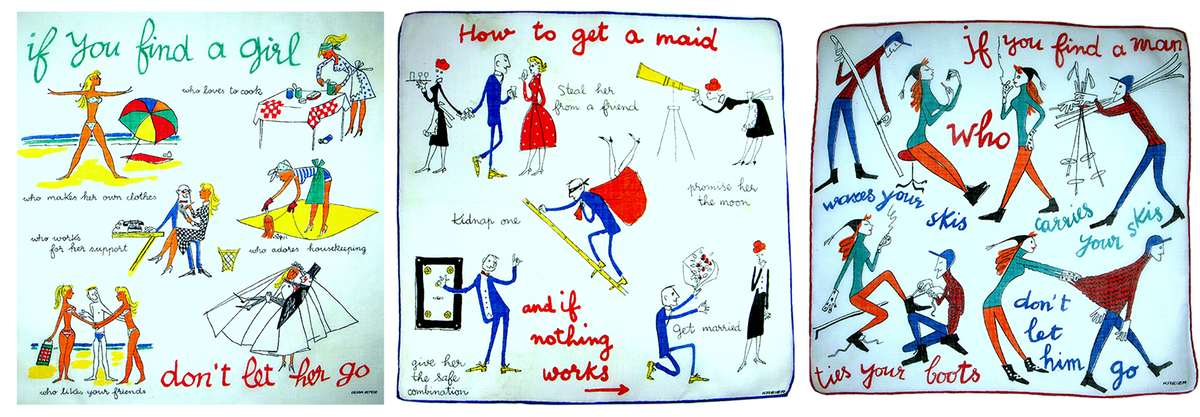

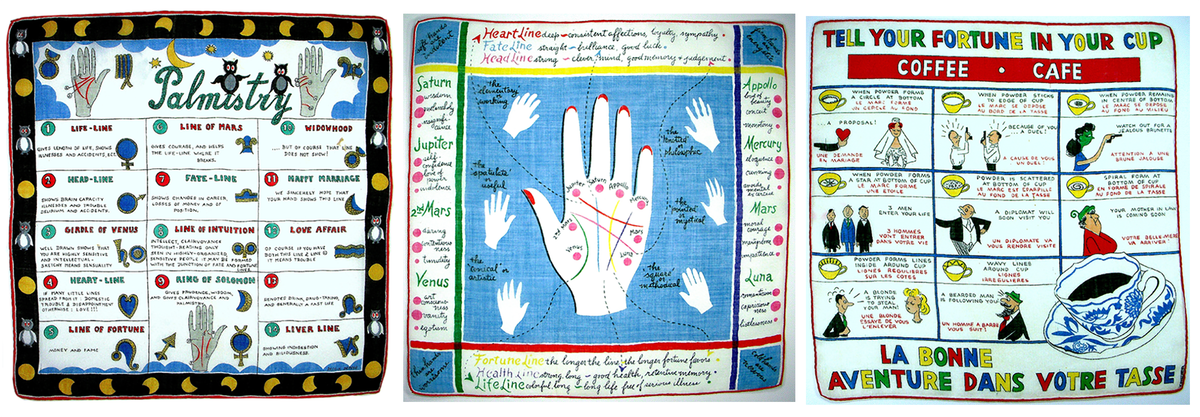

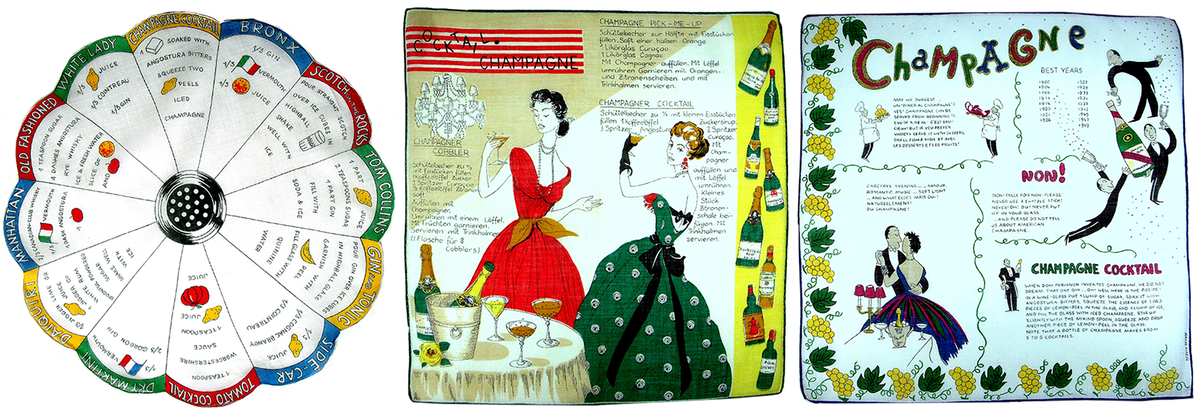

“Handkerchiefs were also fun conversation starters,” Mahony adds, offering handkerchief owners a shorthand to signal their knowledge of certain topics. There were calendars; astrology guides; how-tos on palmistry and graphology; card game rules; travel-related guidelines on customs and tariffs; currency exchange rates; foreign language phrases; dance steps; weight-loss and fitness exercise routines; housekeeping tips; flora and fauna identification; calorie counts; and recipes, for both cooking food and making cocktails.

Businesses and popular leisure activities that grew after World War II show up on midcentury handkerchiefs. The dance instructor Arthur Murray had already expanded his studio franchise in the 1930s, but saw his business model steadily expand in the 1950s. He ordered numerous hankies that depicted not only general dance instructions, but also the phrase, “Arthur Murray taught me dancing in a hurry!” Mahony explains that this was one way people accessorized to show off cultural relevance. This particular usage of hankies was not unlike how we conceive of sports memorabilia or concert merchandise today. “You went to Arthur Murray and learned, then you got hankie with the dance steps on it,” she says. Murray hankies also list the type of dance learned, including the waltz, rhumba, or fox trot.

Eventually handkerchief designers developed cult followings and even paved a path for textile designer trends. Tammis Keefe is among the most prolific handkerchief designers of the mid-20th century, signing her name on her fabrics before it was common for designers to do so. Her bold, colorful designs depicted animals, landscapes, and mythical creatures, and were also used for household textiles and furnishings including dishtowels, tablecloths, and even clothing. “Handkerchiefs are fun to do, and I try to make them fun to give,” she told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1949. Before her death in 1960, she is believed to have produced over 400 of her bright, whimsical handkerchief designs.

Keefe is largely known for her exclusive deals with high-end department stores such as Lord and Taylor, which sold her signature line. But she skirted exclusivity by also signing handkerchief designs as Peg Thomas, in order to sell other designs through lower-tier retailers.

Keefe’s contemporaries, including Pat Pritchard, Jeanne Miller, Carl Tait, and Faith Austin, were among other handkerchief designers of the era to sign their vivid canvases.* In the 1960s and 1970s, Anne Klein and Hanae Mori also signed their designer hankies.

Like any gifted designer, Keefe had high-minded ideas about the seemingly simple handkerchiefs she created. She has been quoted as saying, “Color is the most important factor in design generally, and in handkerchief design, specifically, color prepares the emotions for the design itself, as music sets the mood of the play.”

As the 20th century progressed, handkerchiefs were largely seen as a cult relic, primarily due to stiff competition from disposable tissue manufacturers. Keepsake handkerchiefs continued to pop up intermittently, such as with Monty Python’s 1973 album, Matching Tie and Handkerchief, which indeed came with the matching accessories. And while ladies handkerchiefs were mostly consigned to textile collections and rarely received focus from the fashion world, in the mid-2010s, the handkerchief’s close cousin, the decorative pocket square, re-emerged as a popular colorful accent piece, most notably for dapper men who included them in their blazers.

Despite their small size and seemingly antiquated purpose, handkerchiefs are a strong thread throughout history. With so much historical fascination with these humble accessories, it’s a shame we no longer think that much of hankies, let alone track trends with our pocket squares, laments Mahony. After all, she says, “Handkerchiefs are really a record of history.”

*Correction: This story previously stated that Faith Austin’s first name was Fay.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook