How England Got Its Curvy Cucumbers Straightened Out

The cucumber straightener was a marvel of British horticulture.

In the mid-19th century, England was no country for crooked cucumbers. A curly, misshapen, or discolored specimen might be tossed to the pigs, who certainly wouldn’t mind. But by 1845, more perfect cucurbits were within reach. To straighten out a wayward cucumber, a 19th-century British gardener might have told you, you just needed to give it a little love. And maybe a giant glass straightjacket.

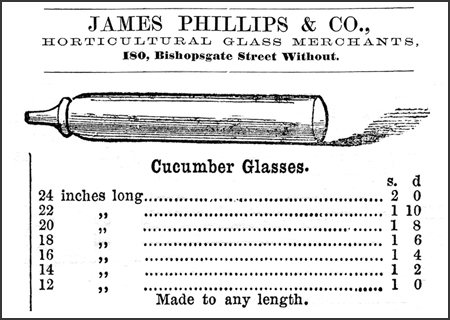

Long, tubular, and made of glass, the cucumber straightener is perhaps the most simple and superfluous gardening tool in history. But in the eyes of British gardeners, it rectified an intolerable perversity: a hooking, twisting cucumber.

Long before England was obsessed with straight cucumbers, it was disgusted by them. The first cucumbers made their way to Great Britain in the 1300s, and inspired great disdain among the English that persisted for centuries. According to 18th-century British writer Samuel Johnson, it was commonly said among English physicians that a cucumber “should be well sliced, and dressed with pepper and vinegar, and then thrown out, as good for nothing.” The vine-growing fruit was even dubbed the “cowcumber,” suggesting the vegetable was so vile it only ought to touch the lips of livestock.

It wasn’t until the iconic cucumber sandwich became popular among Queen Victoria’s family that the produce began to gain prestige. Subsequently, the delicate sandwich became an iconic teatime snack in British high society, and the cucumber, suddenly, was in vogue. To ensure the fruit could be slipped easily between slices of bread, it needed to be sliced thinly and evenly. Which called for a straighter cucumber.

This might not seem like a big deal, but growing straight cukes is no simple task. Cucumbers begin to curve for a number of reasons, from humidity and temperature shifts to poor pollination. Some varieties of cucumbers curl easier than others, too. So unless gardeners really knew what they were doing, they’d likely end up tossing some of the harvest to the hogs.

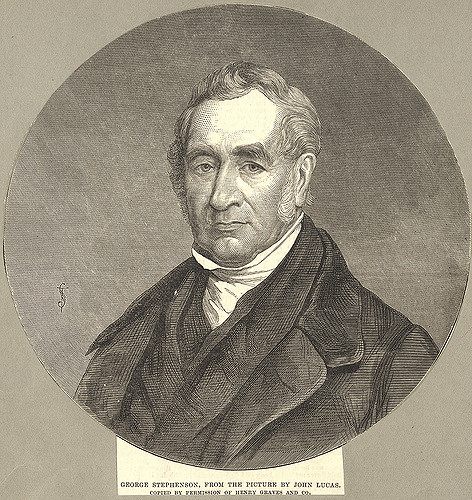

For British engineer George Stephenson, however, leaving a cucumber’s fate up to chance wasn’t an option. A tinkerer from an early age, Stephenson spent most of his life working on the first British railway system. Best known for creating the “Rocket,” an early steam locomotive, and the first public inter-city line for locomotives, he became renowned as the “Father of the Railways.” But he was also a horticulturist at heart, and as his locomotive career wound down, Stephenson took the innovation and perseverance that helped him excel on the tracks into the garden.

Stephenson was no leisurely gardener. Out of passion (and fierce rivalry with his friend Paxton, the gardener for the Duke of Devonshire), he began erecting vineries, pineries, apiaries, melon houses, and forcing houses, where he grew tropical fruits and vegetables. He vowed to grow pineapples the size of pumpkins, and engineered melon baskets from wire gauze to assist their growth. He was largely successful, too, winning a prize for his pines, and growing nationally acclaimed grapes.

His cucumbers, however, gave him trouble. Despite adjusting temperature, light, and the position from which they would grow, Stephenson’s cucumbers would relentlessly curl. Frustrated, the civil engineer crafted hollow glass cylinders in his Newcastle steam engine factory for his Tapton House garden.

The device was a long, delicate, glass tube that fit a growing cucumber like a giant glove. According to landscape architect* and historian Mark Morrison, a wire was strung through the top of the contraption to hang the straighteners in the garden or greenhouse. As the cucumbers grew, the vine would be fed through the tube, so that the cucumber hung vertically like a giant, green, phallic ornament within the narrow glass brace.

When Stephenson removed his cucumbers from the tube, he was pleasantly surprised. The cucumbers, indeed, had grown to fit the straight mold of the glass cylinders they had grown inside. It was said that he showed off the final product to a group of visitors and declared, “I think I have bothered them noo!”

An enterprising lad through and through, Stephenson patented the big glass tube, which became a popular tool for well-to-do Victorian gardeners and farmers. Using straightening glasses was likely a common tactic among those entering cucumber competitions all about size and curvature—or lack thereof. According to the Gardener’s Chronicle, the winner of the 1848 Stockport Cucumber Show clocked in at 22.5 inches long and, most importantly, was “perfectly straight and level as the barrel of a gun.”

However, as 19th-century writer Isabella Beeton pointed out, using a cucumber straightener did not come without risk. “When the tubes are used, it is sometimes necessary to watch them,” she wrote, “in order that, during the swelling of the fruit, they are not wedged into the tubes so tightly that they are difficult to withdraw.”

Eventually, the glass straighteners went out of style. According to Morrison, they died out, like many Victorian-era tools, as the Industrial Revolution hit full stride. “Years ago, all the cucumber straighteners were blown, and all the tools were made by hand by a local blacksmith,” he says. “Once the Industrial Revolution hit and manufacturing started, a lot of the art was lost.” The blown glass tubes were costly, labor-intensive, and, perhaps, not wholly necessary. Morrison points out that simply hanging the cucumbers vertically produces a relatively straight fruit. In the end, the glass tubes were likely replaced by vertical farming methods and the non-curving varietals many cucumber farmers use today.

But even as Stephenson’s glass straighteners disappeared, the desire for straight cucumbers persisted. Largely, Morrison points out, this was a relic of the times and a society structured around royalty. “We joke, of course, the royal family could never eat a crooked cucumber,” he says. But he also notes that there was a practical application: The curvier the cukes, the fewer could fit in a crate or a shipping container.

In fact, as of quite recently, E.U. regulations discouraged dramatic curvature in cucumbers. Until 2008, it was required by law that all Class I cucumbers sold across Europe be “practically straight,” and “bent with a gradient of no more than 1/10.” Though the technology has changed, the appetite for aesthetically pleasing produce hasn’t.

*Correction: This post previously stated that Mark Morrison is a landscape artist. He is a landscape architect.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook