In Ancient China, Pet Crickets Spent the Winter in Opulent Gourds

More than functional, these fleshy fruits developed into a striking art form.

The imperial concubines of China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907) had a rather lively autumn tradition. According to ancient texts, as the weather cooled, they collected crickets and slipped them into tiny golden cages. “These… they place near their pillows, and during the night hearken to the voice of the insects,” describes the eighth-century book Kaiyuan Tianbao Yi Shi. “This custom was imitated by all people.”

That court ladies were cricket-catching influencers might be the stuff of legend, but people did begin domesticating crickets during the Tang to keep their songs close. The insect’s trill has long been beloved as an art; some Chinese people still keep crickets to this day. Notably, the practice led to new forms of craft from the Tang onwards: Artisans began designing containers that ensured the good health of their insect residents year-round. Before the introduction of modern materials like plastic, many crickets divided their time between a summer home and a winter home, like affluent retirees. Simple clay jars kept them cool in warmer months, but to beat the bitter cold, they needed a cozier shelter. And that’s where the gourds come in.

Gourds, it turns out, make for perfect winter forts if you are a small cricket. A good luck symbol in Chinese culture, a gourd, once emptied of pulp, can be dried and lacquered to form a warm, heat-retaining cocoon. The cricket would rest on a mixture of lime and loam at the shell’s base; on especially cold nights, it might receive a cotton pad, according to the late anthropologist Berthold Laufer, who studied these dwellings. To keep them clean, owners would rinse them with hot tea.

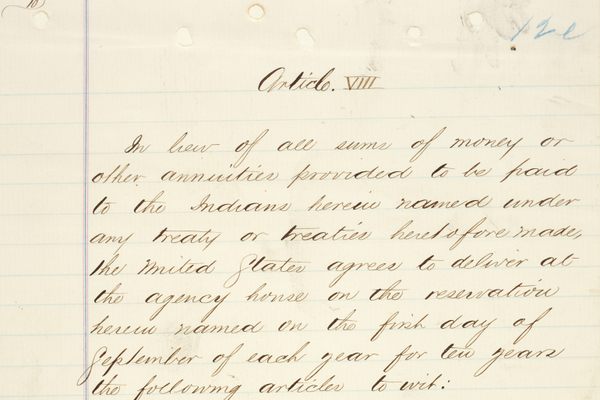

More than functional, cricket gourds developed into a striking art form. The fruits were grown in special clay or wooden molds, some of which are so ornate that they left intricate reliefs, from geometric patterns to landscapes, on the gourds’ flesh. Other gourds were painstakingly incised with a heated metal needle.

Laufer, a cricket breeder himself, learned about the unique gourd-growing process during a 1923 expedition to China. “The flowers are forced into the moulds, and as they grow will assume the shape of and the designs fashioned in the moulds,” he later wrote in Insect-Musicians and Cricket Champions of China, a leaflet published by the Field Museum in Chicago. “There is accordingly an infinite variety of forms: There are slender and graceful, round and double, cylindrical and jar-like ones.”

The anthropologist even pinpointed the method to a single location. The preferred gourd, he wrote, was “said to be a special variety of the common gourd (Lagenaria vulgaris), the cultivation of which was known to a single family of Peking.”

Also known as calabash, this fleshy fruit had to be carefully grown not only for visual allure but also to boost acoustics. Lisa Gail Ryan, the author of a book exploring the cultural history of cricket-keeping, likens the shape of a gourd to that of a musical instrument, as it “determines the tone of the insect’s chirp.” Many are slender, easy to slip into a pocket to enjoy a private concert on-the-go.

Once dried, a gourd was also sliced near its top and fitted with a perforated lid to prevent escapes. Artisans spared no effort in producing elaborate covers, which were often made of tortoiseshell, coconut shell, sandalwood, or ivory.

The Minneapolis Institute of Art owns dozens of cricket gourds, all believed to date to the Qing Dynasty, which lasted from 1644 to 1911. Each has a cover carved with tiny designs featuring flowers, dragons, and other auspicious emblems. These are similar to decorations found on contemporaneous Chinese objects such as snuff bottles and jade carvings, says Yang Liu, the museum’s curator of Chinese art. “Many of these motifs acted as educational reminders for morality or religion, and they were related to Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism,” Liu says.

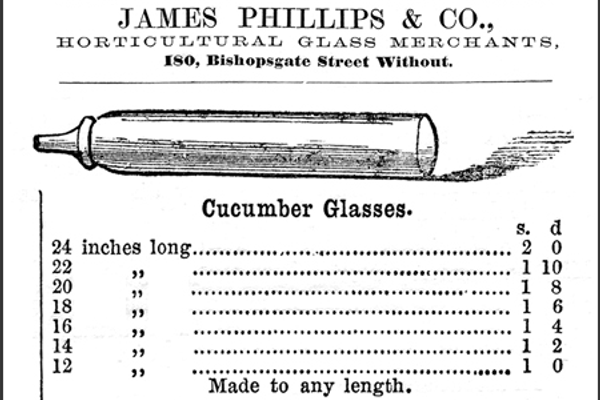

The gourds are part of the museum’s larger collection of related paraphernalia that illustrates the Chinese practice of cricket-keeping. There are delicate accessories including mini bamboo or wooden cages, metal catching nets, and even painted porcelain feeding dishes that once served meals of cucumber, lettuce, chestnuts, and beans.

Other objects, such as cricket ticklers (slim rods used to incite the insects) and a cricket-fighting ring, are reminders of how the hobby eventually turned bloody. In the Song Dynasty, from 960 to 1279, cricket fighting emerged and thrived as sport, with insects forced to battle to the death. They were historically seen, Laufer wrote, as “incarnations of great warriors and heroes of the past from whom they have inherited a soul imbued with prowess and fighting qualities”—which is why some owners laid perished fighters in cricket coffins and tombs.

Whether for sport or for song, crickets are still collected in China, although their dwellings these days are typically mass-produced. The gourd-molding technique had petered out by the time Laufer penned his report—replaced, in his opinion, by “poor modern imitations.” Vendors at specialty markets today are more likely to sell crickets in bamboo baskets, plastic containers, and even toilet rolls that serve as makeshift tubes. These are certainly less beautiful to behold than elegant gourds, but they speak to the enduring value of the cricket’s chirp—still one of the most cherished sounds in Chinese culture.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook