In Medieval Baghdad, Rulers Held Elite Cook-Offs

The “Iron Chef of medieval times” could have serious consequences.

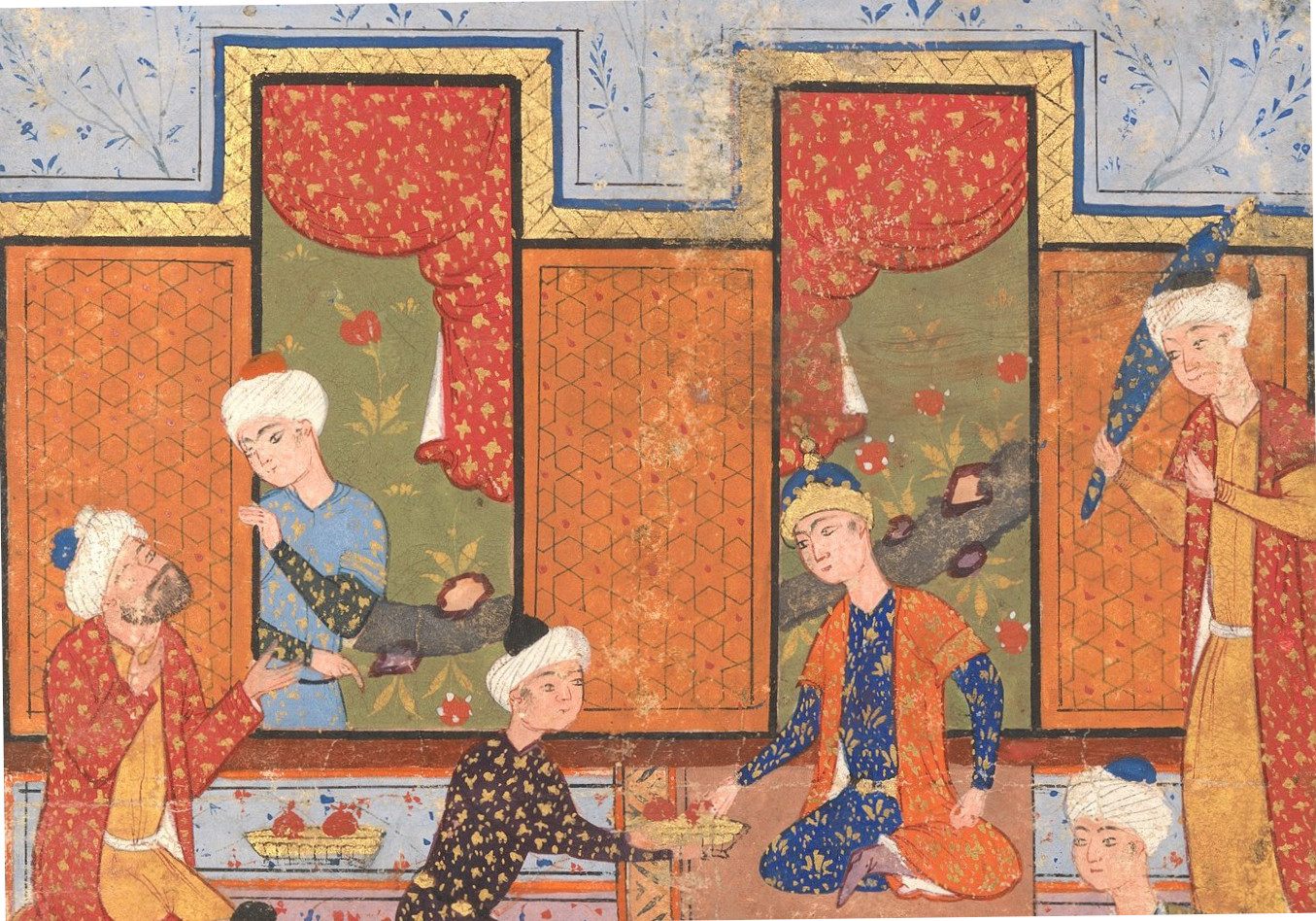

We tend to think of cooking contests as a modern institution, whether featuring Alton Brown or nail-biting comparisons of British cakes. Yet cooking competitions actually have a much longer history. In the food-obsessed culture of ninth-century Baghdad, being a foodie was essential to getting ahead. Stories abound of the caliphs’, or rulers’, passion for cooking, eating, and talking about good food. They even participated in cooking contests, including one that ended in near-execution and exile.

According to Iraqi food historian and scholar Nawal Nasrallah, Baghdad at this time was considered the “navel of the nations”: the center of the world. “They had contacts with the four corners of the world,” says Nasrallah, which meant the wealthy had access to spices from across Asia, citrus from China, and sugar from India. The city had the ingredients for a world-class food culture, and the wealth to enjoy it, as it was the Islamic Golden Age. And while Christianity had strict mores against gluttony, Nasrallah points out that Islam didn’t prohibit the enjoyment of food. “So the whole atmosphere was conducive to creating this kind of activity.”

This obsession with food went straight to the top. One popular dish, judhaba, consisted of a sweet, layered bread pudding cooked in a tannour oven, with a chunk of meat roasted above it. The pudding would catch any drippings, creating a sweet and savory melange. One recipe, made with bananas, sugar, and rose water, was a specialty of Ibrāhīm bin al-Mahdī, who Nasrallah evocatively describes as “the Abbasid gourmet prince.” (The Abbasids were the ruling dynasty.) Vendors sold judhaba in the marketplace, and some caliphs were known to commandeer especially tasty dishes cooked by commoners.

Caliphs may have even cooked competitively. According to one story, the caliph al-Maʾmūn, who reigned in the early ninth century, once faced off against his brother and boon companions. It was an “Iron Chef of medieval times,” laughs Nasrallah. In her description of the event, a cook named ‘Ibāda was present. Described as having a “delightful and mischievous sense of humor,” he was nonetheless jealous when al-Muʿtaṣim, al-Maʾmūn’s brother, cooked a dish that smelled quite good. He coaxed al-Muʿtaṣim into adding a bowl of fermented sauce to his dish, which then gave off a nasty odor. In true sibling fashion, al-Maʾmūn roasted his brother mercilessly. Unfortunately for ‘Ibāda, al-Muʿtaṣim became caliph in 833 and exiled him in revenge, claiming “he was not worth killing,” writes Nasrallah. (‘Ibāda made troublemaking a habit, but must have been a superlative cook. Another caliph brought him back, only for him to be banished again for another prank.)

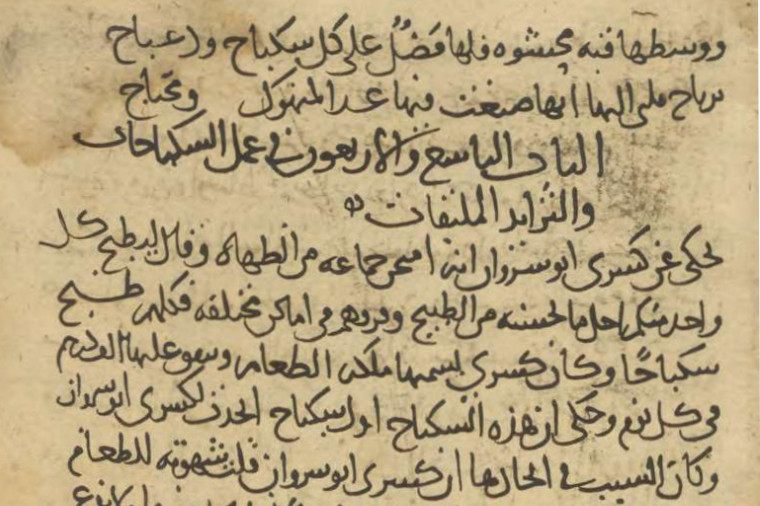

Though Nasrallah notes that there are only a handful of similar stories, the fact that writers inscribed them into chronicles typically devoted to battles and successions means they were considered important social activity. Poets wrote elaborate food poems, and manuals describing how to be an ideal “boon companion” for a ruler emphasized the importance of cooking. One recommended that these men learn a repertoire of at least 10 exotic dishes. It was this gourmand culture that produced the first medieval cookbooks, containing the favored dishes of the elite. Nasrallah herself translated the earliest-known: a 10th-century cookbook called the Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchen. So now we all can face off in the kitchen with our boon companions, Abbasid-style.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook