Why Eating Insects Is an American Tradition

Both Native Americans and colonists enjoyed fried cicadas, grasshopper flour, and insect fruitcakes.

In just over five years, the apostles of insect eating have moved entomophagy in the Unites States and Europe from a Fear Factor sideshow to a regular fixture in food industry trend lists. These entopreneurs, dozens of newly minted bug farmers and cricket-laced protein bar hawkers, built their culinary foothold through compelling arguments about nutrition and sustainability. Crickets, for example, provide leaner protein than animal meats, require minimal feed and water to rear, and produce far fewer greenhouse gas emissions per pound. These claims may be overblown, but they’re effective.

Common wisdom holds, however, that the industry still faces one major headwind: culture. While the vast majority of the world has some history or current practice of insect eating, Europe and America, many insect eating enthusiasts and experts claim, do not. In the absence of precedent, we’re primed to see eating creepy crawlies as loathsome.

There’s a little problem with this common wisdom, though. America does have a history of insect eating. Native communities across the modern United States developed culinary traditions around dozens of insect species, from crickets to caterpillars, ants to aphids. White settlers and other newcomers ultimately denigrated these traditions. But well into the 19th century, they occasionally participated in them, or formed limited insect-eating cultures of their own. In some communities, insect eating remained relatively common well into the mid-20th century; a few continue today.

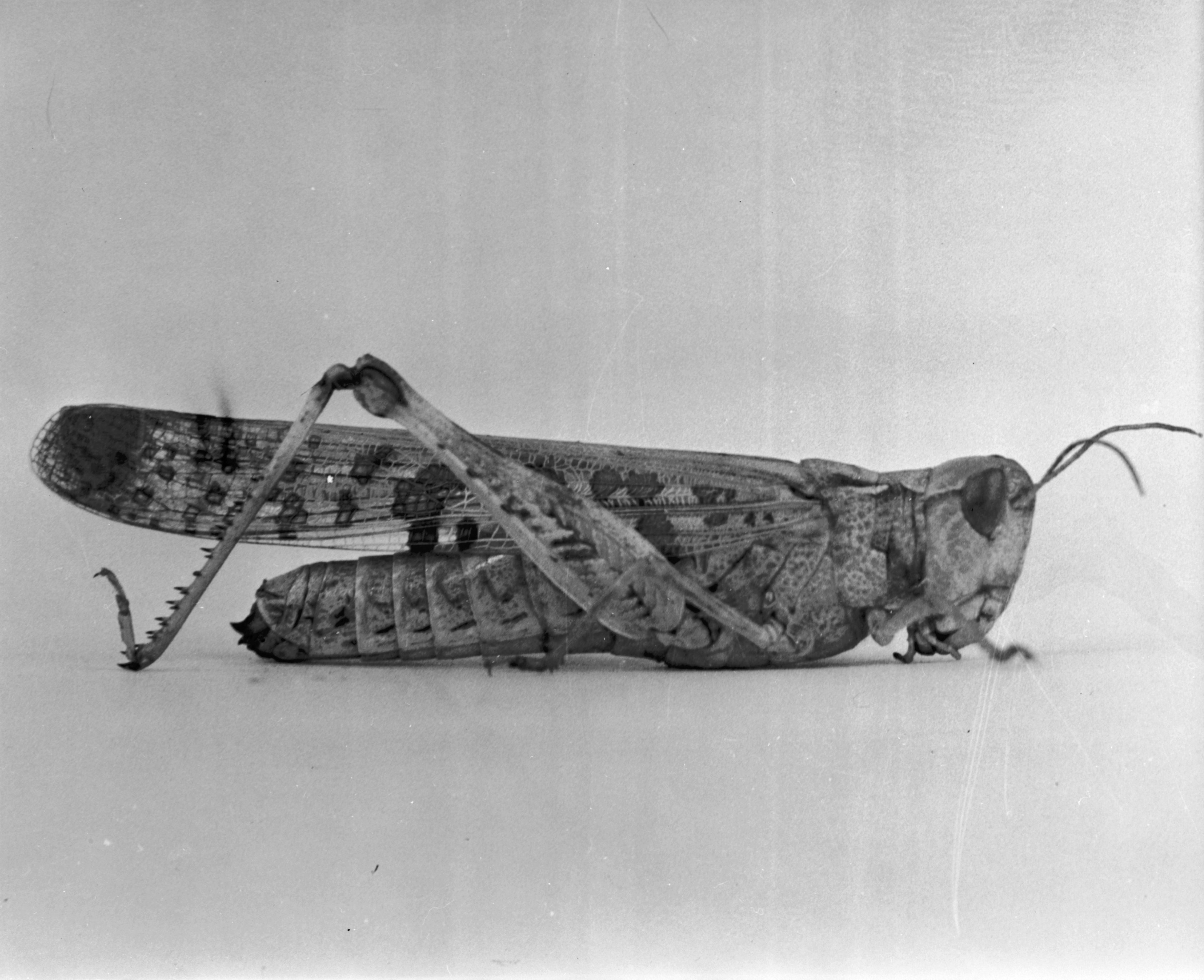

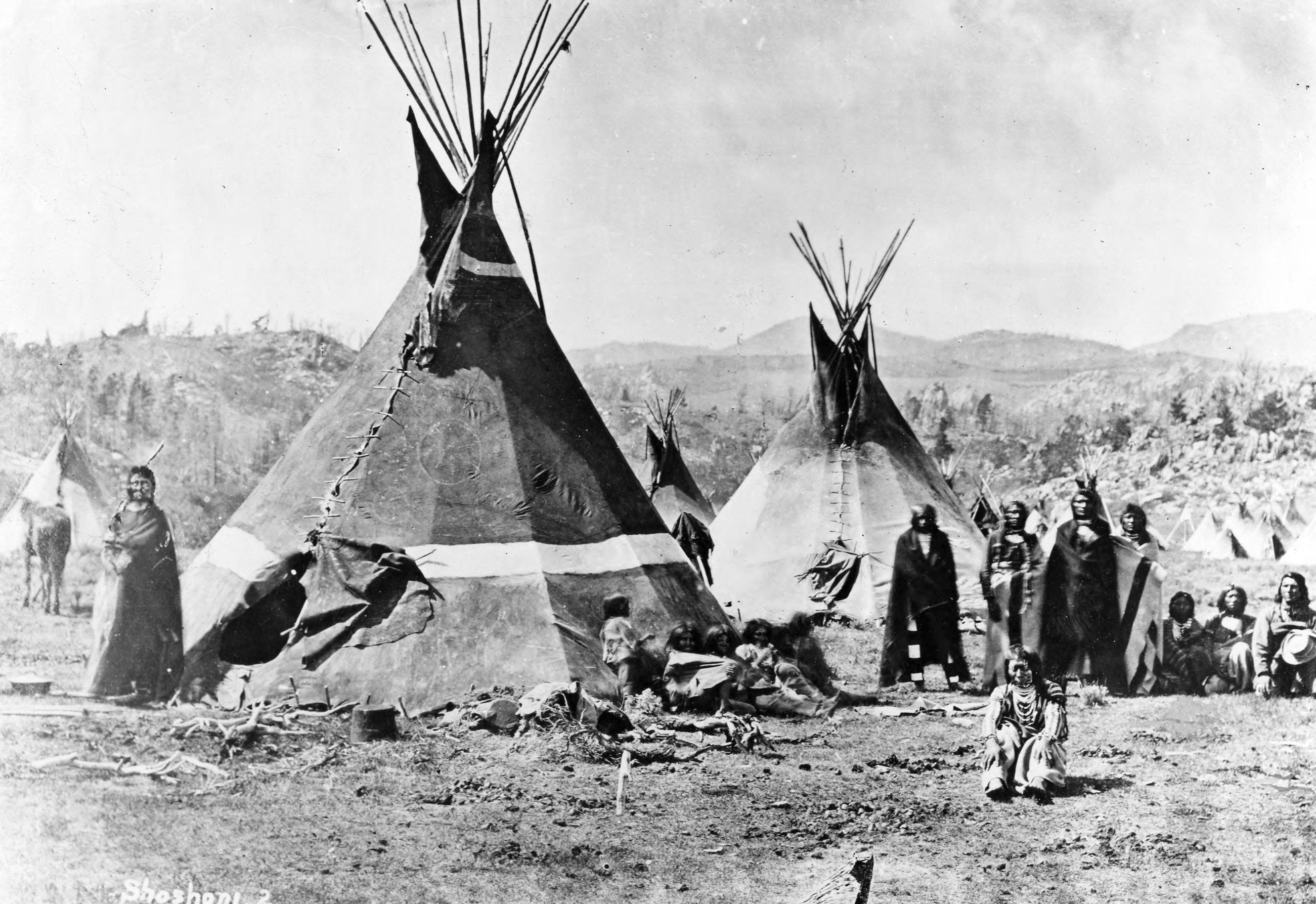

The origins of these foodways are not as well documented as the development of, say, cakes or bagels. But we do know that by the time Europeans and other newcomers encountered American Indians, many had highly developed insect harvesting practices. In the 19th century, the Shoshone and other Native communities in the Great Basin region formed massive circles and beat the brush to drive thousands of grasshoppers into pits, blankets, or bodies of water for mass collection; they then roasted them on coals or ground them into flour. The Paiute and other groups out West dug trenches with precise, vertical walls around trees, then smoked out caterpillars for regularized, large-scale harvests. Some Paiute communities around Mono Lake in California reportedly organized their calendar around the life cycles of certain larvae, as well as other types of small game such as rabbits or lizards.

Some of this insect eating just made practical sense. Grasshoppers were thick on the plains during average seasons, and in heavy swarm years, a plague of hoppers-turned-locusts could blot out the sky. Into the 20th century, lumberjacks in Oregon claimed that caterpillars were so plentiful that, during their month-long feeding season, the sound of their crap falling from the trees was like an unending sleet storm. Harvesting this bounty was a time- and energy-efficient way of gathering protein.

But in many communities, insect eating was not merely a matter of survival or convenience. American Indians with plenty of other options for hunting or harvesting collected insects as a delicacy. A mid-20th century account of the Cherokee in North Carolina notes that they dug up young cicadas, removed their legs, and fried them in hog fat as a treat. Sometimes they baked them into pies or salted and pickled them for later. They also apparently loved roasted cornworms and yellowjacket grubs, which were hardly as convenient to harvest as a locust swarm. The arctic Tlicho reportedly let gadfly larvae grow on meats they’d hunted so they could be picked off and eaten raw as a treat on par with gooseberries. And the Onondaga supposedly enjoyed a good ant here and there for the citrus bite it could add to a dish.

Some groups, including a few communities in New Brunswick, used ants as a medicinal food as well. The Kitanemuk of the western Mojave—and possibly other tribes in south-central California—even consumed red harvester ants as a spiritual hallucinogenic. All told, experts estimate that between 25 and 50 percent of Native American communities have some sort of insect-eating tradition.

Europeans actually had their own insect-eating traditions too, although they were poorly documented. Still, we can see snippets of them in accounts of German soldiers in Italy in the early 17th century snacking happily on fried silkworms, or of people in what is now Ukraine using an ant-based liquor, murashkowka, to make medicinal punches in the early 19th century. But according to David Gracer, an expert on insect-eating history, none of these traditions, to his knowledge, transferred into America.

Colonists did at times interact with Native insect-eating traditions, though. According to archaeologist and insect eating history buff David Madsen, Native Americans in the Great Basin traded an insect fruitcake (a mash of nuts, berries, and insect bits, usually katydids, dried into a bar) to immigrant wagon trains in the mid-19th century. This trade sustained segments of the westward migration in America, and may, according to a 2013 United Nations report, have saved the earliest Mormon settlers in Utah. “One account said something to the effect that, while the initial reaction to [these fruitcakes] was not that favorable, that soon wore off and the settlers ate it with gusto,” says Madsen.

Some settlers even developed their own insect-eating traditions. In 1874, notably, a massive locust swarm decimated crops throughout the Midwest, forcing some farmer-settlers to give up their homesteading lands. To address the food scarcity in the region, Missouri entomologist Charles Valentine Riley developed recipes for eating the locusts, which he managed to get endorsed by a well-known St. Louis caterer and disseminated throughout the region.

Most of these flirtations with insect eating were short-term affairs: matters of survival that lasted only as long as the wagon trains rolled across the plains or the crops were decimated. But a few traditions had staying power. Lumberjacks in Maine and Quebec, for instance, reportedly caught and ate carpenter ants from the early colonial era into the 19th century. “We think they were warding off scurvy,” says prominent insect chef David Gordon, “because they taste citrus-y.”

While settlers may have been, at times, open to eating insects, Gracer points out that the overarching story of white-dominated settlement in America is one of subjugating nature and replicating favored European foodways. He also notes that Europeans especially, and other settlers as well, weaponized unfamiliar practices—including insect eating—as a sign of Native Americans’ inferiority. The 19th century French missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet went so far as to call one Western tribe, the Soshoco, uniquely “miserably, lean, weak, and badly clothed” because they relied on insects more than nearby Native groups. And in the mid-20th century, the entomologist Charles T. Brues notes, viewing other cultures’ insect-eating traditions “served royally to bolster up the feeling of race superiority, Nordic or otherwise.”

Culturally dominant Western sensibilities eventually marginalized any form of insect eating in America. “It probably was a class issue,” notes Rosanna Yau, an editor at The Food Insects Newsletter. “It was probably shameful for Europeans to admit to eating insects, or even lobsters, because it was a poor person’s food.” Industrialization and urbanization also made it increasingly difficult to harvest insects.

Missionaries and settlers heaped open scorn on Native communities, and their foodways were often a target. Writing in 1946, Brues noted that “the recent influx of wide-eyed and hilariously mirthful tourists” out West “made the Indians bashful” about practicing their traditions, including entomophagy. More brutal and systematic tactics came into play as well, such as shipping Native children to boarding schools where they were beaten and coerced into conformity.

It speaks to the power and extent of these traditions that they survived, if under the radar and at diminished scale, in many Native communities well into the 20th century. Anthropologists had no problem finding people willing to show them extant harvesting methods in the 1950s, says Madsen, and newspaper articles attest to caterpillar and grasshopper gathering in the 1990s. “I have heard several current or recent examples of small Native communities gathering and sharing insect foods” to this day across the Great Basin, adds Gracer.

A few accounts suggest that limited entomophagy may have long survived in some white settler communities, at least on the Great Plains. Kelly Sturek of the Nebraska-based insect eating startup Bugeater Foods has heard stories of children eating cicadas growing up. Their families, he says, treated this as normal, not a gross-out childhood dare. If anything, they were chided for spoiling their appetites.

It is not surprising that America’s insect-eating traditions, lived or historical, are little known. Most of America engages with Native history selectively, if at all, points out Jenna Jadin, author of a pamphlet on cicada eating. Native peoples may choose not to put their insect eating cultures on open display given persistent stigmas. Meanwhile, Americans have developed a set narrative about who colonial settlers were, says Sturek. “We were frontiersmen,” he explains. “We hunted. We fished. We farmed. Insects don’t really fit into that.”

As a result, most Americans first encounter insect eating when traveling in (or watching travel shows about) Southeast Asia, where insect eating is mainstream. Even though finding a cultural correlate is usually a good way to push seemingly novel products such as grasshopper bars, most American entopreneurs miss or gloss over this history of local, traditional practices.

The West’s new interest in insect eating opens an opportunity to explore a long-neglected element of American history. Better yet, it’s a chance to offer those with a historic stake in American entomophagy the ability to influence the industry’s development, and perhaps to benefit from the revival of cultural practices once used to denigrate them. By instead failing to explore American insect-eating traditions, indigenous or otherwise, the current trend implicitly erases and marginalizes this history yet again.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook