How 1940s Prisoners of War Escaped Through Their Dreams

The illustration of a dream from a patient in Jungian analysis, 1967. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

This is part five of a five-part series on sleep and dreams, sponsored by Oso mattresses. Read the others here, here, here and here.

Major Kenneth Hopkins, a Ph.D. student in psychology who served as an officer in the British Army during World War II, was captured during the fall of France in 1940 and sent to Laufen, a Bavarian castle that the Nazis used to house prisoners of war. Hopkins intended to keep on working on his dissertation, and began interviewing his fellow imprisoned officers about their dreams every morning. Over two years, he filled a series of notebooks with 640 dreams from the 79 subjects who agreed to play along.

In 1942, however, Hopkins died of emphysema, leaving his work behind.

The notebooks ended up in the Wellcome Library in London, where psychologist Deirdre Barrett, of Harvard University, whose work centers on the analysis of dreams, became intrigued by them in 2011. The story of the data collection was interesting (and a little tragic), but Barrett was particularly drawn to the dreams because of the rare opportunity they presented. “It would be hard to get access to a modern POW population,” Barrett told me. Data on prison dreams, while less scarce, is still uncommon. “And there’s no way to go back and retrospectively look at a Nazi POW camp in World War II!” (Time machines aside.) The Hopkins dream records begged for analysis.

POWs in the compound at Oflag 79 camp for Allied Officers, April 1945. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

So Barrett and a group of Harvard students tackled the task. The group used a metric called the “Hall van de Castle scale” to analyze the Laufen dreams. American psychologist Calvin S. Hall began working with dreams starting in the 1940s; in the ‘50s, he and collaborator Robert van de Castle refined the categories that Hall had developed when analyzing dreams into a systematic method that would let researchers code for dream content. (The pair published a book, The Content Analysis of Dreams, in 1966.)

Using this scale, researchers trying to parse the structure of dreams could code for emotions experienced; settings; types of social interactions; characters; and an array of other “dream elements.” Hall gathered dreams from a global population, and sought to compare frequency of these elements across cultures. Because Hall and van de Castle worked at roughly the same time as Kenneth Hopkins, Barrett and her team thought the Hall/van de Castle findings could be used as a useful point of comparison with the data that came from the prisoners at Laufen.

What did a British POW dream about, while trapped in a Nazi-controlled castle prison camp? “Food appeared with amazing frequency,” the team wrote in a 2013 paper for the journal Imagination, Cognition and Personality. “This was often combined with content about homecomings.” In one long dream of homecoming, an officer visited a restaurant and multiple pubs, eating dishes including “a dish of prunes and custard into which a bottle of ale had been poured.”

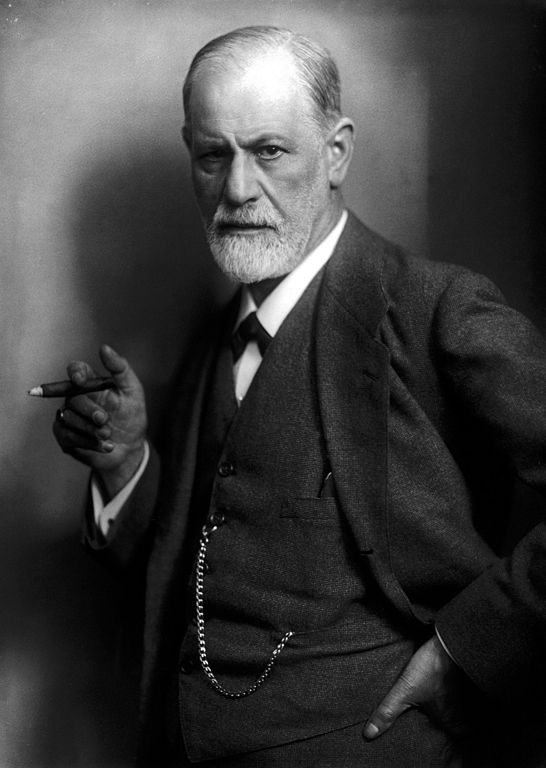

Sigmund Freud. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

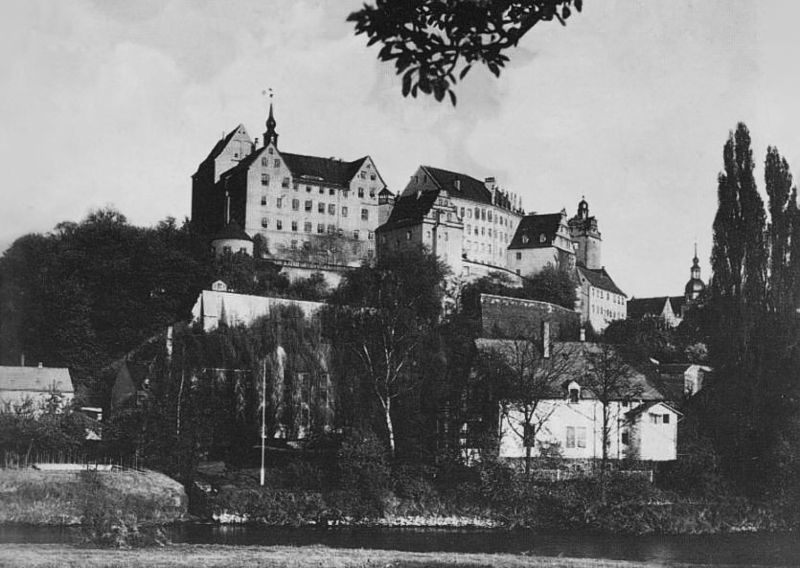

Escape dreams were more common among the POWs than among the larger population. Barrett found while researching the history of Laufen that there had been a famous POW prison break there, and she found that three of the escapees had been part of Hopkins’ research; the question of escape was on their minds. One example:

Myself and three others escaped from prison. We lay up all day near the Slav border and we were going to cross at night. As evening wore on, we got prepared and were lucky enough to get a car. Around midnight we got into the car. The one driving the car was dressed as a Gerry [German] officer. Woke up sweating although with effort not with fear.

An earlier depiction of a solder’s dream, from 1861. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Although the Harvard team found some horrifying dreams in Hopkins’ notebooks (“Two Englishmen running from Germans intentionally dive into a vat of green acid. I am horrified. I want to help them, but I knew I would be too late”), they reported that on the whole, the POWs seemed not traumatized, but dampened by their condition. “The POW dreams are blander on most dimensions,” the team writes. “They contain less of any kind of social interaction—positive or negative,” and if the POWs dreamed of sex, those dreams were “peculiarly frustrated.” (One dream featured “a proposition from a friend’s wife that involved wearing a massive, painful prophylactic.”) In their blandness and featurelessness, the Laufen dreams are similar to the dreams found in other prison populations.

Colditz Castle, where the ‘Laufen Six’ were sent after escaping from Oflag VII. POWs frequently dreamed of escape. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

If Kenneth Hopkins had survived the war, and returned to his Ph.D. study in 1945, what would he have done with the dreams he collected? Barrett says the evidence is somewhat scanty, but there are some clues. “It looked like he went in wanting to do a Freudian-oriented analysis; he had scoring categories with Oedipus complexes and masochism and anal obsessions, but the whole scoring [system] is not there, and I assume he’s meaning those pretty metaphorically,” she says. Hopkins doesn’t seem to have been conceiving of the population that he was analyzing as particularly distinct; he seems to have seen his POW analysis project as a matter of convenience, substituting his fellow imprisoned officers for the subjects he would have used at his university, and not focusing on their unique situation.

Yet, Barrett says, one of the letters from Hopkins’ advisor that was preserved with the notebooks remarked on the interesting possibilities for analysis that his sample raised, indicating that the advisor, at least, knew that his student had an intriguing set of data on his hands. As she put it, “Who knows how this might have played out when he got back?”

Sponsored by Oso mattress. OSO mattress is customizable comfort created with Reverie’s DreamCell(TM) technology. Shop the mattress now to discover the sleep for you.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook