How Early Feminists Helped Revolutionize Birding

Bird watching with binoculars. (Photo; goodmami/flickr)

To identify a bird, you used to have to kill it.

Birds are masters in “how not to be seen,” being often both small and fast, and terribly brownish. To distinguish beyond the most minute differences in colors and sizes, and to get the birds to stay still enough to depict them accurately, early ornithologists had to have dead birds to see any sort of detail. The naturalist perhaps best known for this is John James Audubon, whose elaborate grid setup allowed him to depict birds in more natural poses, rather than the stiff profiles many other ornithologists had been painting. But as Florence Merriam put it, “It is impossible…to name all the birds without a gun.”

She would know, as the author of one of America’s first field guides, Birding through an opera glass. And Merriam’s gender may have been an anomaly at a time when science was male-dominated, but she was actually the center of an important Venn diagram. Conservation, birding and female reform movements all came together in the 19th century to radically change how we study avian life.

Early interest in birds (besides hunting) involved collecting eggs and skins for their aesthetic value, or deep study by scientists or naturalists. It was either an expensive hobby or an academic pursuit. But by the end of the 19th century birding was morphing into a middle class hobby, and one heavily influenced by the women’s reform movement.

Mabel Osgood Wright, c1900. (Photo: Library of Congress)

As rapid growth created a new middle class, there were now many educated American women ready to take up a slew of causes, from abolition to temperance to the vote. Conservation was one of them. The push for conservation was fueled by both westward expansion and by the trend of women wearing plumage in their hats, one of the biggest causes taken up by the newly- formed Audubon Society. “Both Merriam and [Mabel Osgood] Wright [author of field guide Birdcraft] responded to the plume trade not with accusations directed at the women who chose to wear bird hats, but with a positive strategy of describing living birds as worth appreciating,” according to Spencer Schaffner, author of Binocular Vision. Birds were valuable in and of themselves, not for the beautiful feathers they could give.

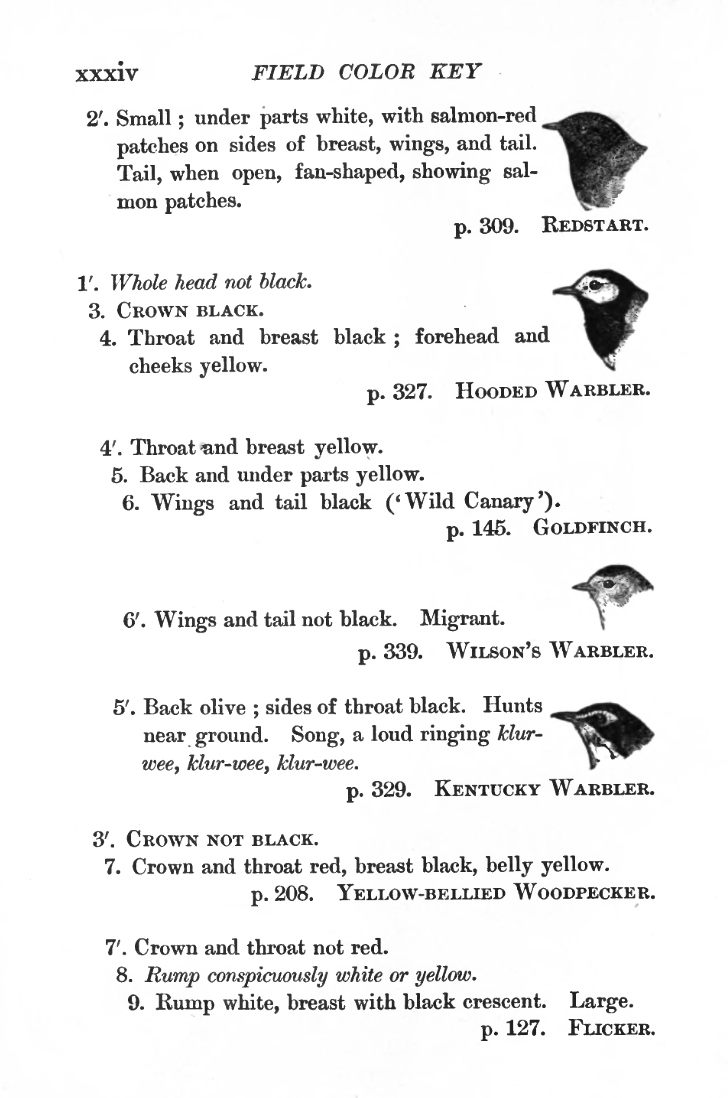

In its first iteration, Merriam’s 1883 guide had few images, and rather she suggested going to museums so “you can compare bird skins with the birds you have seen in the field.” Instead of images, the guide relies on florid prose about common birds to the American East Coast. For instance, Merriam says of a Robin “Everything about him bespeaks the self-respecting American citizen.” The language is important; Merriam described in the bird not as a thing to be watched or even owned, but as a living, breathing citizen of the world. And as illustrations, photographs, and now apps have made identification visual rather than verbal, our relationship to birds has changed.

Without or with limited illustrations, words were the tool to change hearts and minds. Birds were not animals, but citizens. They were “handsome and useful” creatures, with songs like “musical laughs,” the way Wright described them her 1897 classic Citizen Bird, in between faux-conversation between a doctor and a group of children. In Birding through an opera glass, Merriam calls a crow “a very Shakespeare among birds,” and a ruby-throated hummingbird a “winged spirit of color.” The goal wasn’t just to identify birds, but to commune with them and with nature.

Florence Merriam’s 1897 book Birds Through an Opera Glass. (Photo: Boston Public Library/flickr)

Women’s influence on birding can be seen in many places during the turn of the century, not just as birding enthusiasts, but active proponents for conservation. Women founded the Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1896, the first state-level Audubon Society. Merriam, Wright and Harriet Mann Miller (another birding author, known by the pseudonym Olive Thorne Miller) were members of the American Ornithologists’ Union, and in 1929 Merriam became its first fellow, and in 1931 won its Brewster Medal for her comprehensive study on the birds of the American Southwest. Wright founded Connecticut’s Birdcraft Sanctuary, near her home in Fairfield, in 1914. And Miller “won the respect of professional naturalists by the precision and authenticity of her recorded observations,” which she wrote in everything from adult bird guides to children’s books.

All three women accomplished this by “humanizing” their avian subjects, something many male naturalists and scientists seemed to have no interest in doing. In that way perhaps women were better suited to introducing birding as an amateur hobby to the world. Though these women became professionally accomplished, most women (or really, anyone) did not have the educational or societal opportunities to become full-fledged scientists and researchers. Women like Merriam, Wright and Miller understood that, and also understood that popular opinion was paramount in the fight for environmental conservation. Rather than addressing scientists, they addressed their peers–educated women and men, but also anyone with access to a park or a backyard. Wright dedicated Citizen Bird “to all boys and girls who love birds and wish to protect them.” Women understood birding could be for everyone.

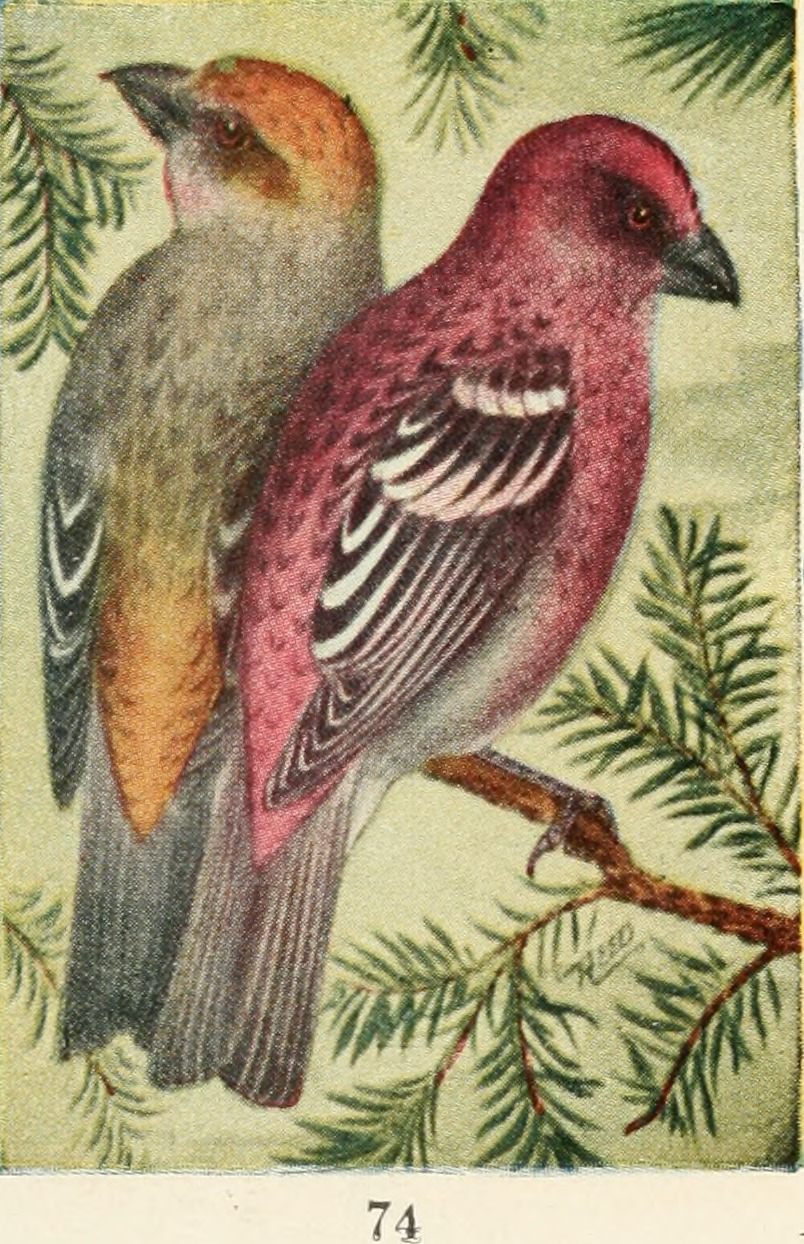

An illustration from a 1916 copy of Chester Reed’s Bird guide: land birds east of the Rockies from parrots to bluebirds. (Photo: Internet Book Archive/flickr)

Thanks to these women, by the 1900s birding was a bona-fide hobby, and publishers began to understand there was a market in field guides. In 1905, Chester Reed published Bird Guide 2: Land Birds East of the Rockies, the first guide to feature color illustrations of birds alongside the beautiful descriptions (a Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker was described as having “gained some ill-repute” for boring through trees to get to the sap). The descriptions were interesting, but they were secondary to the art—it doesn’t matter what a Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker eats, because if it looks like the drawing it is one.

In 1934 the trend continued with one of the most influential field guide writers of the 20th century, Roger Tory Peterson. A Field Guide to the Birds sold out of its first 2,000 copies, and went through six subsequent printings. Part of its success was due to the “Peterson Identification System,” which focused on visual cues rather than technical details. There were a few reasons why this became possible. For one thing, binocular (and opera glass) technology had advanced so that birds were easier to spot from afar. For another, Peterson’s guide could be filled with color illustrations of birds because color printing technology had advanced to the point where it was affordable for things like small field guides.

A page from Florence Merriam’s 1898 Birds of village and field: a bird book for beginners. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

To this day, most field guides follow the Peterson model, with color photography making it even easier to carry accurate images with you into the field. And now the next wave of birding guides is taking over—the birding app. Now it’s often as simple as typing in the color and location of a bird to figure out what it is.

When the objective is identification, images don’t need prose. Color printing, then photography, then digitization has made it so that it no longer matters whether the crow’s call “is like the smell of the brown furrows in spring,” or whether the catbird is “unmistakably a Bohemian.” But in a way, the prose themselves ensured that as well. Merriam, Wright, and the others did their job. We’re not stuffing plumage in hats by the thousands, nor wiping out entire species for sport. We no longer need to feel drawn to birds as characters because whether or not they’re worthy of wonder is no longer a question. But without the women who first gave language to these creatures, we might not have so many left to observe.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook