How Humans Went From Hissing Like Geese To Flipping The Bird

Disaffected teens in Berlin carry on a storied tradition. (Photo: Sascha Kohlmann/Flickr)

It usually takes two hands to type out a message. But there’s one digit that, flying solo, can get more across than a whole screed: the middle one, a.k.a The Finger, a.k.a The Bird.

If the intent behind the gesture is viscerally obvious, the name isn’t. No one is turning over a chicken—so why do we call it flipping the bird? It turns out that this fowl expression began its incubation millennia ago, in the classrooms and coliseums of of ancient Rome. Since then, it has winged its way through all the most important arenas of public life, from the theatrical stages of 17th century Britain to 1950s Saturday morning cartoon screens.

According to etiquette historian Roger E. Axtell, the middle finger is “the most ubiquitous and longest-lived insulting gesture” in the world. Anthropologist Desmond Morris has collected various examples of its use as a cultural insult everywhere from Russia to the Middle East. In its preferred Western form–extended between two bent knuckles—it’s generally understood to represent another, visually similar body part (and to suggest particular actions performed by that other appendage—its Greek name, “katapygon,” means “given to unnatural lust.”)

The young punks of Ancient Greece used it to rage against stodgy teachers and overblown orators. One of the best jokes in Greek literature, from Aristophenes’ 423 B.C. play The Clouds, involves a student “demonstrating” a poetic meter to his tutor, Socrates, by flipping him off. Despite its seeming crudeness, this is actually a pretty clever response, as the meter in question, the dactyl, also means “finger.” (Socrates does not agree, replying, “You are as low-minded as you are stupid.”)

In the 2nd century B.C. the philosopher Diogenes–pictured here in a portrait by Jean-Léon Gérôme–insulted the famous orator Demosthenes by sticking up his middle finger and saying “there goes the demagogue of Athens.” (Image: Walters Art Museum/WikiCommons Public Domain)

The Romans called it digitus impudicus, or “the insulting finger.” In private, it could be used to “check the evil eye,” but in public it was always an aggressive gesture—the Emperor Caligula made certain of his subjects kiss his finger instead of his hand, a scandalous request that underscored his antagonism toward them. Though the gesture lost popularity during the Middle Ages, it re-emerged in Britain around 1712, when a newspaper called it a sign of disrespect similar to a stuck-out tongue.

Meanwhile, rowdy crowds were perfecting a louder, more communal sign of aggression: angry avian noises. People have been hooting in dramatic displeasure since 1300, writes linguist Ben Zimmer, long before they began mooing, meowing, or channeling displeased creatures from other branches of the animal kingdom. Aggressive hissing, in the style of an angry goose, is much older—it was also a staple of Roman audiences—but became even more popular in post-17th century Britain, which was rife with drama on and off the stage. A sentence from a 1612 biography of controversial Jesuit Robert Parsons describes the banished priest being “hissed out the College with whouts [hoots] and hobubs [hubbubs].” Readings of the Riot Act was routinely met by mobs of hissers, and an 1810 court case protected the rights of British theater audiences to “express by applause or hisses the sensations which naturally present themselves,” so long as they hadn’t planned to hiss ahead of time.

By the middle of the 19th century, all those squawks and shouts were condensed under one name—“the goose,” the nightmare of dramatic actors all across Britain. An 1848 issue of The Theatrical Times features the story of one Mons Jacques Rusé, a visitor to England who “gooses” an actor and gets expelled from a theater. After a passer-by explains his offense, Rusé is even more confused than before: “Why say you ‘goose’ if you mean ‘hiss’?” he asks. (Imagine how confused he would be today.)

A goose demonstrates why his species was tapped to represent cross-cultural anger. (Photo: This Incredible World/Flickr)

A few decades later, the insult been generalized further. According to an 1890 dictionary of British slang, hissing and hollering was now called “the big bird,” and you could either give it (fun) or get it (less so). “When an actor or actress gets the big bird, it may be from two causes: either it is a compliment for successful pourtrayal of villainy… or, the hissing may be directed against the actor, personally, for some reason or another,” writes the author. Renowned 19th-century dramatist H.J. Byron reported that when a performance got a bad response, his actors would say, “The bird’s there!”

Over the next half-century, the notion of “the bird” as a nonverbal expression of displeasure evolved until it eventually dovetailed with the infamous digit. It’s difficult to trace this evolution in public life, partially due to obscenity laws that constrained some normally telling forms of expression, like television and radio, but certain birds winged past the censors. One example might be “A Tale of Two Kitties,” a Merrie Melodies cartoon from 1942 in which a pair of hungry cats, Babbitt and Catstello, try to capture a tiny bird. The cartoon’s chief animator, Bob Clampett, had originally drawn the bird featherless, in order to make him even more helpless-looking but the Hays Office, then in charge of enforcing obscenity laws, insisted he cover up. In response, Clampett wrote this exchange between the frustrated hunters:

Babbitt: “Give me the bird! Give me the bird!”

Catstello: “If the Hays Office would only let me, I’d give him the bird, all right!”

As hissing and hooting wouldn’t draw the censors’ wrath, we can assume Catstello was referring to something less family-friendly—perhaps a flick of the middle claw. We can’t know for sure, though, as linguist Jesse Sheidlower points out that “the problem with puns and double entendres is that you can’t always be sure what the pun is,” and says the cat could just be threatening to give us all a raspberry, also considered too rude for TV. Fittingly, the actual bird involved would prove himself a master of cute-meets-aggressive, lisping his way adorably through violent attacks on cartoon cats for decades. Audiences today know him as Tweety.

People began flipping the bird instead of just giving it sometime in the 1960s, about a decade after the groovier American cats first started warning each other not to flip out or flip their lids. Some theorize that “flipping the bird” implies turning criticism back on whoever had originally given it. Sheidlower, however, says this is impossible, and that “the “flip” refers only to the making of the gesture.”

Still, one of the earliest written instances of the phrase involves a reversal. In 1967, the folk music magazine Broadside describes how the members of the Grateful Dead “flipped ‘the bird’ to the audience, tuned their instruments, blew up amps—for what seemed like FOREVER—then disappeared, leaving people disappointed and brought down.” Whether they knew it or not, the Dead were continuing the legacy of a Roman actor named Pylades, one of the earliest known bird-flippers, who was kicked out of Italy by Caesar Augustus after giving the digitus impudicus to a hissing audience.

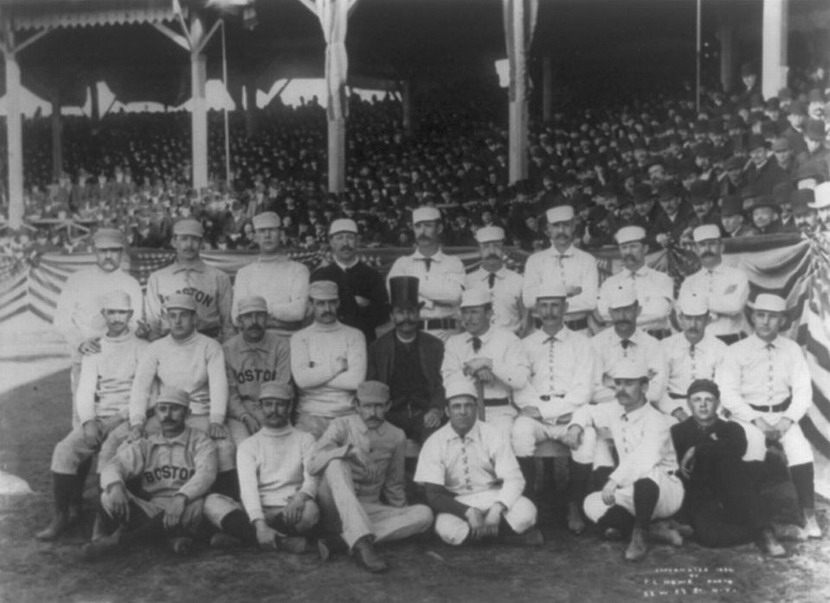

Boston Beaneater Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn (top row, far left) flips a subtle bird during a group photo with the New York Giants, a rival team. (Photo: 19c Base Ball/Public Domain)

Since then, the bird has taken off. It remains not only evolutionarily successful, but endlessly adaptable, winging its way across cultural, physical, generational and taste borders. Now it’s much more than just a hissing goose: Johnny Cash’s ur-bird, set free in Folsom Prison in 1969, might be best described as a standard-bearing peacock; M.I.A’s 2013 Super Bowl bird heard ‘round the world was some kind of mockingbird; and the teens that mill about flipping each other off are like a flock of parrots, imitating each other and their older siblings in order to fit in. Legal scholar Ira P. Robbins, over years of compiling bird-flipping stories, has found that these days, “the middle finger gesture serves as a nonverbal expression of anger, rage, frustration, disdain, protest, defiance, comfort… even excitement at finding a perfect pair of shoes.”

So the next time someone flips you the bird at a traffic light, think of it not as a crow you’re supposed to eat, but as a proud eagle, arcing across the sky, all of human history borne under its wings. And then, if the spirit moves you, flip it right back.

Sculptor David Černý installed this evocative artwork, called “Gesture,” near Prague Castle right before the 2013 elections. (Photo: Jindřich Nosek/WikiCommons CC BY 3.0)

Update, 12/2: An earlier version of this article stated that a 1967 issue of Broadside contained the earliest known written instance of the phrase “flipping the bird.” It actually appeared before that, in the 1966 diary of a Vietnam War pilot. Thanks to Jesse Sheidlower for the correction, and we regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook