How the Vatican Investigated a Modern Miracle at a Leprosy Settlement in Hawaii

One day in 1999, Audrey Toguchi made a pilgrimage to the island of Molokai, to visit the grave of a man she had never met. Passing through the gate in a low cobblestone wall, where stray cats sometimes rested in the shade of St. Philomena Church, the elderly woman and her two sisters entered the graveyard. A few palm trees twisted towards the sky; beyond those stretched the open sea. Mrs. Toguchi walked to the side of the church and came to the grave, a tall marble monument festooned with rosaries and leis. She began to silently pray. Please, Father Damien. Put in a good word for me.

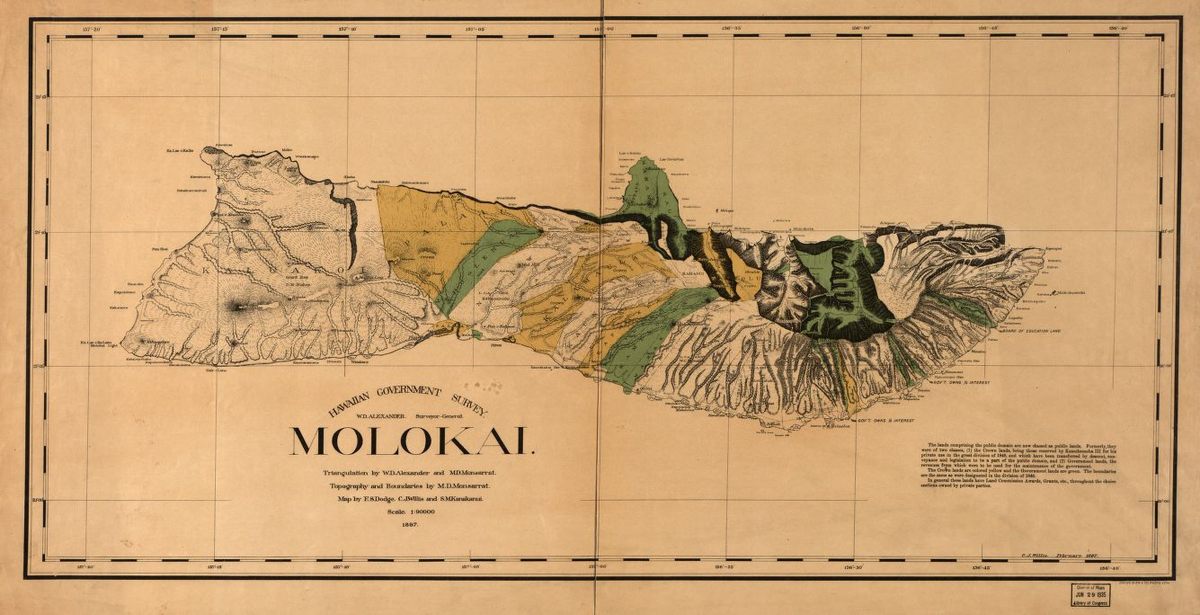

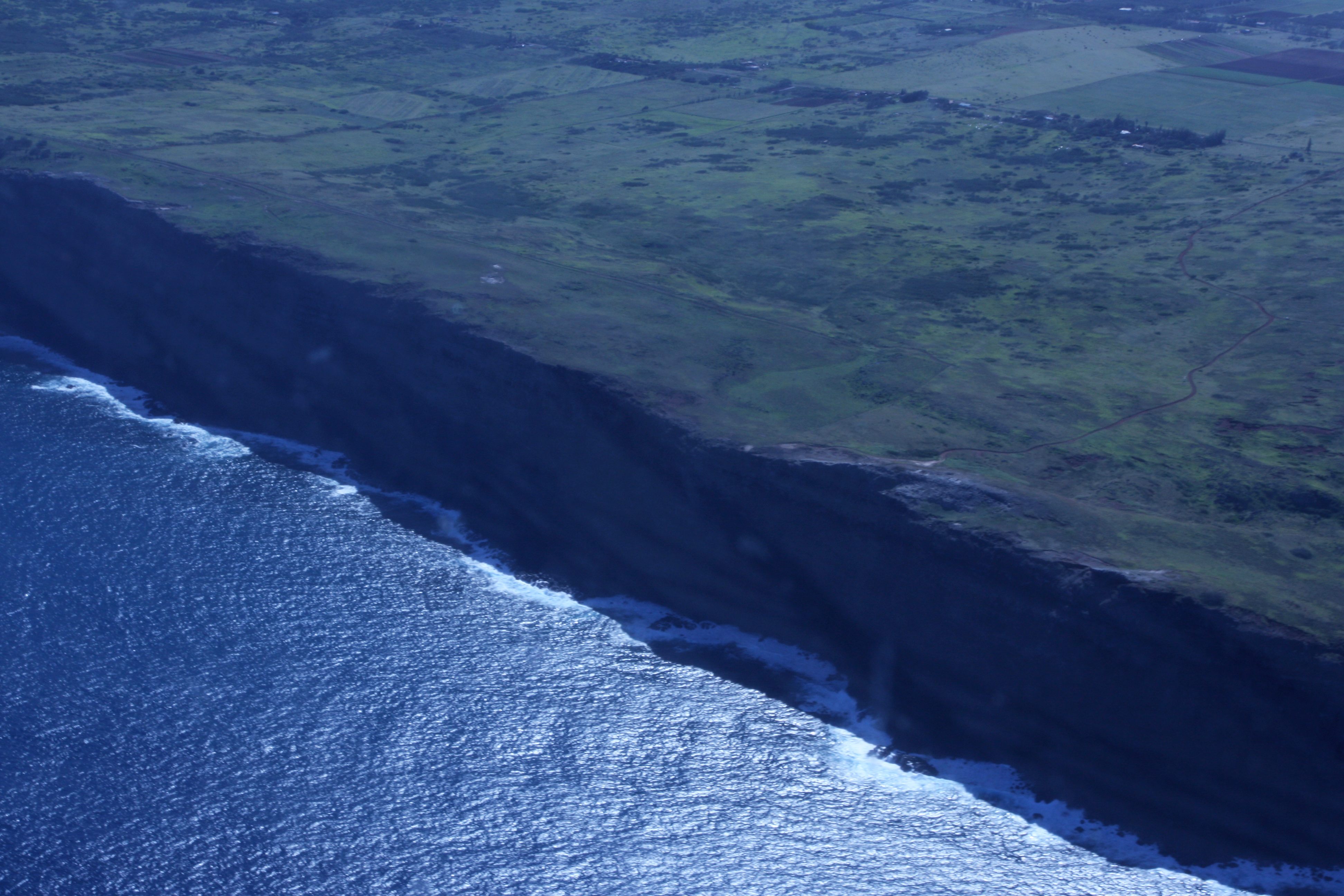

She had not traveled far. As an airplane climbs above Honolulu, the island of Molokai is often visible as a small blue mass, though dim and distant enough to waver like a mirage. Approached from the north, Molokai is a fortress: a vast wall of seacliffs rises above the surf, towering thousands of feet high and stretching for miles from end to end. Near the midpoint of that wall there juts from the base, suddenly and improbably, a low, level shelf of land that the early Hawaiians called Kalaupapa (“flat leaf”). That peninsula has a peculiar history. When, in the mid 19th century, leprosy grew rampant in the Hawaiian islands and panicked public health officials sought a suitable place to isolate the ill, they turned to the small tongue of land protruding from the north face of Molokai. Bound by the sea on all sides and walled off from the rest of the island by the tall cliffs to the rear, Kalaupapa was a natural prison.

It was a dark chapter in Hawaiian history. Bounty hunters roamed the islands in search of suspected leprosy cases; families were torn apart by what they called “the separating sickness.” Since there was no cure for leprosy, to be sentenced to Molokai was to be sentenced to death. The prisoner-patients arrived by the boatload, and if the surf was too rough for landing, they might be cast into the sea and made to swim to shore. Misery reigned on the peninsula, which acquired an unofficial motto: Aole kanawai ma keia wahi—in this place there is no law.

Top: Father Damien’s grave on the island of Molokai (Photo: David Zax). Above: An aerial view of Kalaupapa village on Molokai. (Photo: Alden Cornell/flickr)

Top: Father Damien’s grave on the island of Molokai (Photo: David Zax). Above: An aerial view of Kalaupapa village on Molokai. (Photo: Alden Cornell/flickr)

Into this land of exile came Father Damien de Veuster. The young Belgian missionary volunteered, in 1873, to go to the forsaken place—“the self-exiled priest,” one admirer later described him, “the one clean man in the midst of his flock of lepers.” Newspapers trumpeted his good works, with reports of how he tended to the sick, how he built churches and homes, how he consoled the dying with promises of an afterlife. His bravery and charity became the stuff of legend, and upon his death, many clamored for his canonization. Though he might have seemed a shoo-in for sainthood, a small minority cast doubts on Damien’s character, claiming the man had “lived evilly” with women. Without believing the darkest of the charges, some members of Damien’s own missionary order of the Sacred Hearts were reluctant, at first, to advance a cause for his sainthood.

But by the mid-20th century, Damien’s order finally proposed him for canonization, beginning a long vetting process by the Vatican. Damien’s body was exhumed from its grave on Molokai and returned to his native Belgium; soon, the Church began to pore over all writings by and about Damien for clues to his life. By the late 1990s, the Vatican had declared Damien “Blessed,” an intermediate step towards sainthood.

However, one crucial piece of evidence of Damien’s sanctity was still missing: a miracle.

According to Catholic doctrine, God is the ultimate font of all miracles, but saints, like members of the president’s cabinet, can sometimes persuade the executive to act. If Damien had indeed made it to heaven—if his life had indeed been virtuous—then he ought to have influence with God: he ought to be able to deliver a miracle.

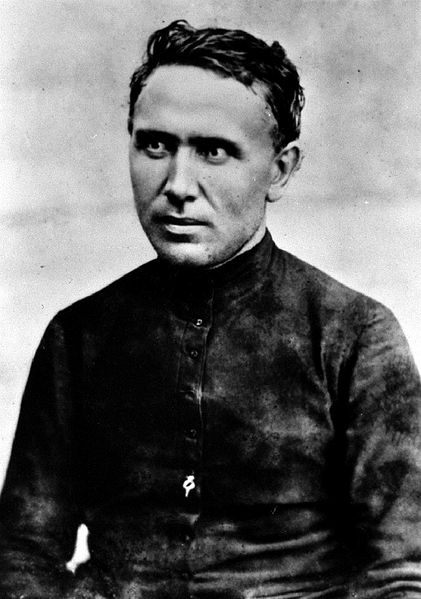

Father Damien in 1873, the year he went to Molokai. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Father Damien in 1873, the year he went to Molokai. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

By September of 1998, Audrey Toguchi needed a miracle. An x-ray had revealed three wispy masses in the retired schoolteacher’s lungs: metastases from a tumor originally found near her hip. The doctors told her that surgery was impossible, and that chemotherapy might extend her life a few months at most. Her surgeon, Dr. Walter Chang, told her there was nothing he could do. The cancer would take her life.

Declining the chemo, Mrs. Toguchi turned exclusively to prayer. She had been deeply devout and prayerful from an early age. Throughout her life, she had prevailed on the Holy Spirit, or the Blessed Mother, or Saint Joseph, or many other saints for help in matters great or small: during her exams in college, which she was the first in her family to attend; or much later, when her husband was ill; or most recently, the time she had to negotiate with a rude contractor. She said her rosary three times a day and never missed a weekend mass at St. Elizabeth Church, her vibrant congregation in Aiea, the Honolulu suburb in which she lived. Her whole world was prayer, she’d say.

That piety ran in the family. Her sister Velma could rustle up prayers around the diocese the way a deft canvasser turns out votes, and when she had learned of her sister’s illness, Velma had called upon the nuns of Regina Pacis, the retired priests of the St. Patrick Monastery, and the children of Kapahulu Pre-School. She also phoned a Sacred Hearts priest she knew named Father Christopher Keahi, and asked him for advice. Father Keahi suggested that Mrs. Toguchi might pray to Father Damien. Who better, he suggested, than this man who had loved and cared for afflicted Hawaiians?

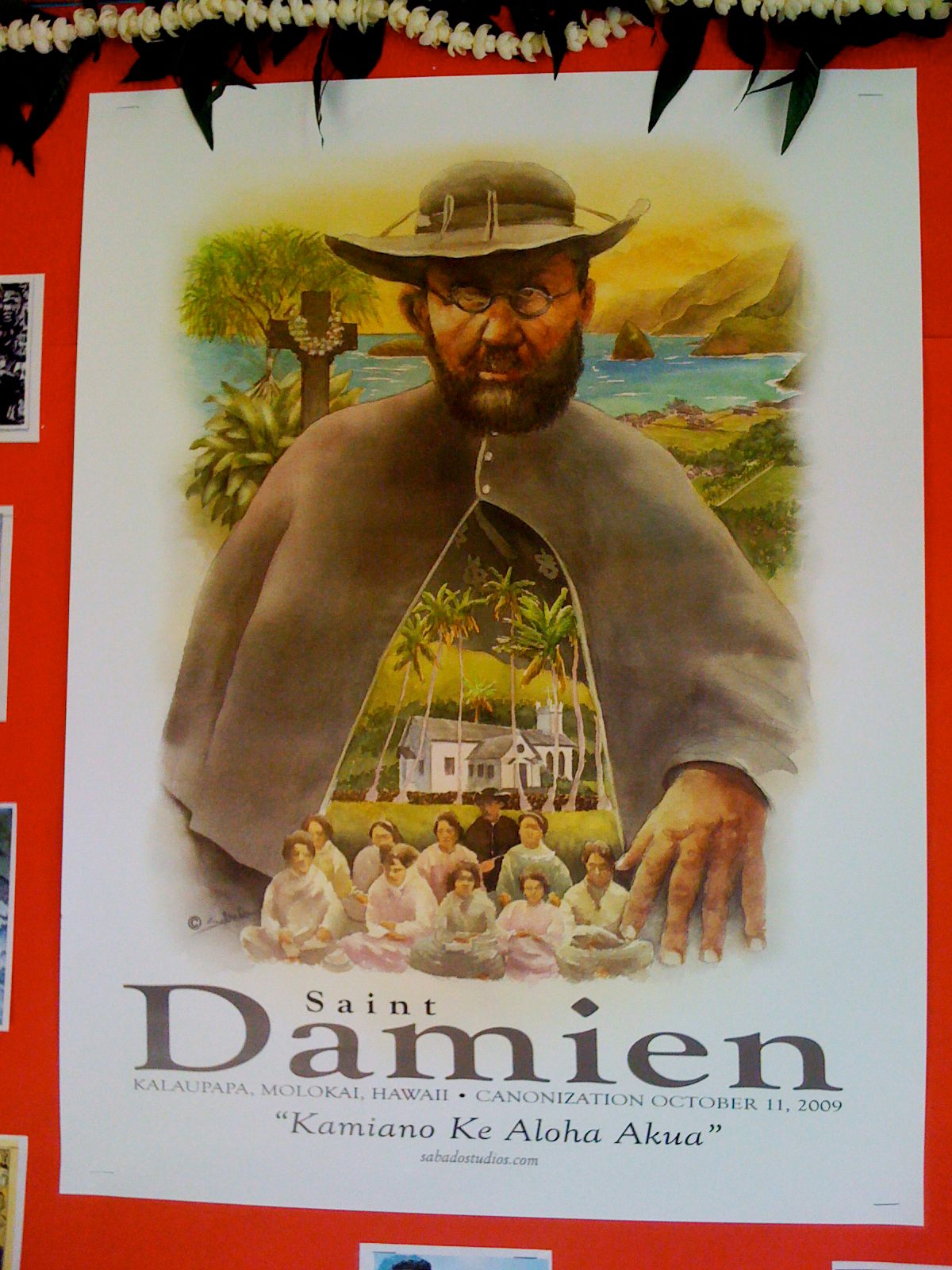

A Father Damien poster at a Catholic school on Oahu. (Photo: David Zax)

A Father Damien poster at a Catholic school on Oahu. (Photo: David Zax)

The idea resonated with Mrs. Toguchi: her own aunt, uncle, and grandfather had all been banished to Kalaupapa. And she could still remember the day when she was only eight years old and Damien’s coffin was paraded down 4th Street in Honolulu, passing many tearful observers on its way to the wharf, and then to Belgium. She never forgot how he had earned the people’s aloha, their love.

She eagerly told another priest, her longtime friend Dan MacNichol, of her plan to visit Molokai. After they spoke, Father MacNichol, who had seen terminal patients in denial before, got out his calendar to see if he had time next month to perform a funeral.

Then something remarkable happened. Upon her return to Honolulu, Mrs. Toguchi’s doctors noticed something unusual in a follow-up x-ray. It appeared that her cancer—her vicious, aggressive, metastasized cancer—hadn’t spread at all. In fact, looking closely, it seemed to the doctors as though one of the masses had become smaller. Another x-ray the following month showed all three masses were shrinking, and one the month after that showed them smaller yet. Finally, an x-ray in early spring showed her lungs to be completely clear. “She appears to have had a spontaneous complete remission, which is unexplained and thus far durable,” her oncologist noted in a report.

As word spread from one member to another of Mrs. Toguchi’s team of doctors, no one could explain what had happened. It was simply unheard of for someone to survive a pleiomorphic liposarcoma with lung metastases.

“I don’t know how you did it,” one of her doctors told her.

But it hadn’t been her, Mrs. Toguchi explained serenely. She had had help, she said, from above.

The churchyard of St. Philomena. (Photo: Library of Congress)

If the question of whether Father Damien was worthy of heaven concerned the Vatican, it had concerned Damien even more. His whole life was an attempt to answer it.

Born Joseph de Veuster in Belgium in 1840, to a family of farmers, he was seized with religious fervor at a young age, enthralled by the stories his mother read from a book of saints’ lives. By his teenaged years, he felt certain it was God’s will for him to become a priest like his older brother Pamphile, and that to refuse the call would jeopardize his eternal soul: “the choice of a life to which God calls us decides our happiness after this life,” he wrote his parents. “[I]f God calls me, I must obey.”

He joined a missionary order, the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, and chose the name Damien after a patron saint of doctors. A photograph taken when he was 23 shows him standing in imitation of St. Francis Xavier, a crucifix held to his chest, his smooth plump face pursed in seriousness.

Damien prayed to St. Francis that he might be sent to the missions. Soon, his chance came; Sacred Hearts missionaries were needed in Hawaii. “Farewell, my dear parents: we will never again feel the joy of embracing,” he wrote. He felt sure, though, that they would spend eternity together—provided that they lived pious lives. To that end, he encouraged his father to “think more of your salvation” and to “meditate every day on the love of God, on death, the last judgment, eternity, the gravity of sin, or on some other great truth.” He recommended reading The Imitation of Christ or the lives of the saints.

An 1897 map of Molokai. (Photo: Library of Congress)

An 1897 map of Molokai. (Photo: Library of Congress)

After five months at sea, Damien arrived in Hawaii—“a corrupt, heretical, idolatrous country,” he wrote—in March of 1864. He served first on Hawaii’s Big Island. “Ah! do not forget this poor priest running night and day over the volcanoes of the islands in search of strayed sheep,” he wrote his parents. “Pray night and day for me, I beg you! Have prayers said for me at home, for if God withdraws his grace from me for an instant, I would immediately be plunged into the same mud of vice from which I want to rescue others.” One day, finding a native Hawaiian making a sacrifice at a volcano’s rim, Damien met the man at the edge of the fire and “seized the opportunity to give him a short sermon about hell.”

After learning of the plight of the exiles of Molokai, Damien realized that he “was to carry out the plan that Divine Providence had for me.” Volunteering to serve at the leprosarium, Damien landed on Molokai on May 10, 1873, and spent the first few nights in the churchyard, beneath the cemetery’s lone pandanus tree. The only other lodging was in huts with the “unclean,” a frightening prospect.

In a letter to his brother, Damien described the symptoms of leprosy. Numbness was often a first sign; many learned they were sick only after scalding their skin at a lamp or stove without realizing it. Soon the body grew discolored, and ulcers opened. As the flesh was eaten away, wrote Damien, it gave off “a fetid odor; even the breath of the leper becomes so foul that the air around is poisoned with it.” Once, at Sunday Mass, he was so overcome by the smell that he nearly had to flee from the church. Sometimes the sick went about with worms writhing in their sores, like cadavers. “I sow the good seed with tears,” he wrote Pamphile. “From morning to night I am in the midst of physical and moral misery which chokes my heart; nevertheless, I strive to be joyful so that I can lift the spirits of my poor people.” He returned to his refrain: “I present death to them as the end of their troubles and their entrance into heaven, if they trust God.”

St. Philomena Catholic Church, Kalawao, in 1905. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The graveyard beside St. Philomena—“this fine garden of the dead”—became his favorite place on the island to go and say his rosary, to remember the departed, and “to meditate on the eternal happiness which a great number of them already enjoy.” He even chose, much in advance, the site for his own grave, and once shooed away officious gravediggers who tried to break ground beneath the pandanus tree. They likely thought it strange for a man to reserve a place for his corpse when he was so clearly in the full bloom of youth and health. Those who saw Damien around these years called him “strong as a Turk,” “of good physique, upright in his carriage,” “a well knit, stocky man.”

A later visitor to Molokai said that to live in the settlement without catching the disease was like “a man to live in a fire without being burnt.” Yet in 1878, when he had been at Molokai for five years, Damien had few complaints—a slight tenderness in the joints and some tingling in the extremities, hardly anything of note. Damien’s continuing health was all the more remarkable because he was notoriously careless in his dealings with the sick, who were welcome in his hut at any time to share a bowl of poi or pass around a pipe.

In his letters, Damien professed to have little doubt as to the source of his good fortune. He had written his brother in 1873, “I have been here six months, surrounded by lepers, and I have not caught the infection. I consider this shows the special protection of our good God and the Blessed Virgin Mary.” The pious had their own preventive medicine.

Dr. Chang outside the St. Francis Medical Center. (Photo: David Zax)

The halls of Honolulu’s St. Francis Medical Center, where by 1999 the surgeon Walter Chang had spent most of his career, were haunted by the ghosts of Molokai. The hospital had been founded in 1927 by nuns of the Order of St. Francis, one of whose prominent members, Mother Marianne Cope, was Damien’s successor at Kalaupapa. The walls held photographs of Damien and his flock; of Mother Marianne standing solemnly by Damien’s bier; of Mother Marianne and her flock. Even a quick trip to Pathology required Dr. Chang to pass beneath a towering diptych in watercolor of Mother Marianne in full habit, overlooking the Molokai settlement.

As he entered his seventies, Dr. Chang retained the irreverent, impish energy that led his nurse to call him a “rascal.” He was surrounded by Catholic imagery day after day, but it meant little to him. He often brought in the latest anticlerical Dan Brown thriller, making no effort to hide the cover from the Franciscan nuns with whom he worked. Though raised Catholic, as the youngest of six children in a Chinese immigrant household in the nearby projects of Palama, he abandoned the faith young. As a teenager, he once asked a priest that if God made the universe, then who made God? Dissatisfied by the priest’s evasive answer, Dr. Chang had from that day forth considered himself a skeptic.

Nevertheless, as he examined the series of x-rays from Mrs. Toguchi—this one, with the three wisps signaling death to anyone trained to read them; that one, with the wisps having grown smaller against all odds; and these, the last, which showed lungs apparently free from disease—he knew that he had borne witness to something remarkable and mysterious. The work of a clinician is technically complete once the patient is cured. But somehow Dr. Chang felt as though his work had just begun.

This statue of Father Damien has stood outside the Hawaii State Capitol in Honolulu since 1969. (Photo: David Zax)

This statue of Father Damien has stood outside the Hawaii State Capitol in Honolulu since 1969. (Photo: David Zax)

Like many Hawaiians both religious and secular, Dr. Chang admired Father Damien deeply and had followed the news of his slow progress towards sainthood. Although Dr. Chang hesitated to believe in miracles, he was convinced that for the Catholic Church, at least, the x-rays and biopsies of Mrs. Toguchi’s cure might be seen as evidence of Damien’s presence in heaven. Those who know Dr. Chang well remark how his convictions can turn into obsessions. “When my father believes he’s correct,” says his son Carter, also a doctor, “he will debate or argue till he is proven right or the other person gives up and turns away.”

Dr. Chang approached Father Christopher Keahi, the Sacred Hearts priest who had first suggested that Audrey Toguchi pray to Damien, and whose hilltop office outside Honolulu is today cluttered with pencil portraits, paintings, and busts of the priest. In a letter that Father Keahi later wrote to a Sacred Hearts representative in Rome, he recalled the talk with Dr. Chang: “he told me when we met that he would challenge any physician to debate him in regards to Audrey’s case,” reported Keahi. “I tried to subdue his enthusiasm by reminding him that Rome treats such cases with meticulous and methodical examination.”

While the Vatican Secret Archives do hold the occasional dossier on the multiplication of food or on two ships narrowly missing each other in fog, the vast majority of documented Catholic miracles are medical cures. Cures figure prominently in the Bible, after all: the first Biblical prayer for healing comes after God strikes Moses’ sister Miriam with leprosy, and the Gospels report that Jesus healed many from that ailment and others.

A Father Damien tapestry in the offices of an Oahu priest Father Christopher Keahi. (Photo: David Zax)

A Father Damien tapestry in the offices of an Oahu priest Father Christopher Keahi. (Photo: David Zax)

But another central reason for the emphasis on cures is that for centuries, the Church has wanted its miracles to be well documented, and doctors are meticulous record-keepers. Following criticisms of the Reformation that miracle stories were sentimental hokum, the Vatican instituted stringent guidelines for what constitutes a miracle. A cure must be sudden, complete, lasting, and—most importantly—inexplicable by contemporary science. The Church privileges medical testimony, and it retains a panel of its own doctors, mostly renowned Italian (and Catholic) professors of medicine, who scrutinize the evidence submitted from around the world by miracle claimants. Very few alleged miracles make it past the “Consulta Medica,” as the body is called.

“In other words,” Father Keahi continued in his letter to Rome, he had explained to Dr. Chang that the miracle certification process was a slow and careful one. Dr. Chang had nonetheless impressed Father Keahi with his presentation. Keahi had fortunately retained his correspondence with Audrey Toguchi from around the time of her cure—he had a habit of keeping thank-you letters to look at in later years. He now transferred all this correspondence into a special file, thinking it might be useful as evidence.

Rome designated Father Joseph Bukoski, a Sacred Hearts pastor in Maui, to oversee any investigation into a miracle. Father Keahi thought this a wise decision, since Father Bukoski was well versed in canon law and had skillfully steered Damien in the mid-90s to beatification, the final step before canonization. For his work, Father Bukoski had even been knighted by the grateful king of Belgium. Father Keahi mailed all his Toguchi correspondence to Father Bukoski, since he was evidently “the best person for the task.”

Then, in August of 2002, the bishop removed Father Bukoski from his post on Maui, following an investigation of the diocesan Standing Committee on Sexual Misconduct. “When I was 15 years old,” the priest’s victim later told the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, “Father Joseph Bukoski gave me drugs and alcohol, waited until I passed out and then sexually assaulted me.” The paper also reported that Bukoski confessed to abusing the boy.

The seacliffs of Molokai, viewed from Kalaupapa. In the 19th century, if the surf was too rough for a ship’s landing here, new leprosy patients arriving at Kalaupapa were cast into the water and made to swim to shore. (Photo: David Zax)

We live in a world in which dark truths remain hidden, in which those who are popularly revered are later exposed to have done terrible things. This is why the Church demands miracles, Bishop Larry Silva said one day, sitting in a parlor of the diocesan center nestled in the side of one of Oahu’s green mountains. “I think we have to be very careful about who we canonize, and I think this is why the Church has come up with this process…. To really propose that person as someone who you can say for sure, ‘This person is in heaven, this person is worthy of our emulation,’ I think those divine signs are important.” When Pope John Paul II had the chance to eliminate the miracle requirement in 1983—many within the Church argued it had grown too arduous—he did not do so, though he did cut the number of miracles required from four to two. Later, he said that miracles were “like a divine seal which confirms the sanctity” of a saint.

A Consulta Medica doctor, poring over the Toguchi files a few days before Christmas in 2002, declared them “extremely interesting,” adding that it was “strongly recommended to summon a diocesan process.” In Honolulu, the bishop assembled a tribunal consisting of priests, notaries, and a physician. Over several weeks in March and April, the tribunal invited Mrs. Toguchi’s pulmonologist, her cardiologist, her oncologist, her radiologist, and her surgeon. The phrase “Catholic tribunal” may have first evoked, at least for Da Vinci Code fans like Dr. Chang, images of solemn stone rooms faintly illuminated by tapers. In fact, the meetings were held in a brightly lit conference room at the chancery office, where a water cooler stood inertly in the corner.

The tribunal’s expert physician, Dr. Philip Jones, began asking questions of the doctors. Might the radiation that had been previously applied to a tumor on Mrs. Toguchi’s hip have scattered to hit the tumors in her lung, he asked? Unlikely, replied the doctors; besides, the lung tumors only grew after the radiation therapy. Might an injection of doxycycline Mrs. Toguchi received have cured her, given that a related drug had been shown to cause cancer to regress in some mice? None of the doctors thought this likely, either.

St. Philomena Church. (Photo: David Zax)

St. Philomena Church. (Photo: David Zax)

In miracle tribunals, a cure is assumed natural until proven otherwise, a position arrived at through a lengthy process of elimination. Though they examine happier subjects, notes the historian Jacalyn Duffin in her book Medical Miracles, miracle tribunals share some methods of the Inquisition, which was similarly a product of 16th century Counter-Reformation reforms. Both types of investigation “centered on a forensic, even skeptical, approach to assertion, argument, and interpretation,” she writes, and came to be “predicated on doubt and demonstration.”

After examining the files of 1,400 miracles, Duffin concluded that one of the most helpful things a doctor could do in a miracle trial was to express surprise. In this, Audrey Toguchi’s doctors succeeded beyond measure. “Once this metastasizes to the lungs the ball game is over,” said the pulmonologist. “A curiosity,” said her oncologist. “Highly remarkable,” concurred the cardiologist. “Extraordinary,” said Dr. Reginald Ho, a past president of the American Cancer Society. In a supplementary tribunal conducted later, a doctor named Winlove Suasin confessed, “I’m trying not to be emotional about it, trying to be very intellectual, trying to be removed from my faith because I don’t want my testimony to be discounted just because I’m a Catholic. People may think, ‘Oh, she’s biased.’ If I was a Buddhist, she would make a believer out of me.” Suasin concluded, “Even Dr. Chang, who is not Catholic and doesn’t believe in anything, sees this.”

When it came time for Dr. Chang to testify, he navigated a narrow course between scientific scruple and inklings of religious excitement. “Now, I don’t call it a ‘miracle,’” he said cautiously. “I call it a remarkable, extraordinary event.” Then, as if worrying he had hedged too much, he ventured, “Now, it is inexplicable, unexplainable by the laws of nature.” Then, taking a new tack, he tried combining scientific precision with grandiloquence. “If I may, to the point of sounding overly confident, it is well evidenced, well proven, well documented, and well biopsied that it had spread to her lungs, and it’s now disappeared, and all the x-rays have subsequently showed she has no evidence so there is nothing to biopsy again.” Finally he said it outright: “to phrase it in a layperson’s term, it’s a miracle.”

The tribunal also summoned Mrs. Toguchi’s husband, her sister, her two priests, and Mrs. Toguchi herself. Not until she entered the room did Father Robert Maher, who held the title of “Delegated Judge” on the tribunal, realize that he recognized her—the perpetually smiling, wrinkled old lady with large glasses, fond of muumuus and the color pink, who could reliably be seen sitting in the front pews each weekend at St. Elizabeth’s morning mass. As Mrs. Toguchi answered the questions put to her, in a slow, slightly raspy voice that moved with the playful lilt of a kindergarten teacher, she brought a new levity to the room.

Asked her ethnicity, Audrey, who is mixed-race, responded, “Chop suey.”

“How did it change your life?” someone asked her of her cure.

“I pray a heck of a lot for other people.”

“Do you?”

“Every single day, I pray three rosaries and have a litany that I do, all made by myself. I walk every day, I have been told to put in one hour. And if you just walk the same path every day, do you know how boring that can get? But when you put your hand on your rosary and you pray, your mind is not on the scenery, it’s on, up there. And believe me, I feel sad for people who do not realize the wealth of help up there.”

Of Father Damien, she summed up: “He’s my friend. I went through hell and he was there, and so was the dear Lord.”

By April 16, 2003, the tribunal thought its work complete; its members sealed all documents and transcripts in a ceremony and sent them to Rome. As to the ultimate cause of Mrs. Toguchi’s spontaneous regression of cancer, the tribunal reached no conclusions. But that, in fact, had always been the hope. Miracle tribunals are perhaps the only form of investigation whose goal is to end in a position of ignorance.

The theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer warned against such a notion of divinity, writing in 1944 that he thought it wrong to use God “as a stop-gap for the incompleteness of our knowledge. If in fact the frontiers of knowledge are being pushed further and further back (and that is bound to be the case), then God is being pushed back with them, and is therefore continually in retreat.” John Paul II admitted in 1983 that it appeared “cases of physical healing are becoming more rare,” and the rate of certified miracles at the famous shrine in Lourdes, France, has slackened over the past few decades. Might future scientists be able to account for Audrey Toguchi’s cure, even if current medicine could not? “Certainly we expect that there is some mechanism that occurs, but we are not able to identify what it is,” her oncologist, Galen Choy, had told the tribunal, suggesting that to predicate divinity on science—a constantly shifting, mutating, self-revising entity—carried risks. “We are to find God in what we know,” concluded Bonhoeffer, “not in what we don’t know; God wants us to realize his presence, not in unsolved problems but in those that are solved.”

For the time being, though, as for the past 500 years, the Church continues to hitch the fate of its miracles—and thereby the confirmation of its saints—to the state of contemporary science. On October 18, 2007, at 9 AM, after two diocesan investigations in Honolulu and many delays in Rome, the Consulta Medica convened to discuss the allegedly miraculous healing of Audrey Toguchi. The judgment was unanimous: her cure was quick, complete, and lasting—and inexplicable, in that it “radically undermined the nature of neoplastic pathology which inexorably should have led to the death of the patient.”

The Hawaii Catholic Herald, reporting the development near the end of October, cautioned that the case still had to be examined by a commission of theologians. Mrs. Toguchi’s cure had the features of a miracle, it was true. But, the Church still needed to know, had it really been caused by Father Damien?

The grave of Saint Damien in the crypt of the church of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts in Leuven, Belgium. (Photo: FaceMePLS/flickr)

Damien, too, thought he discerned divine favor in his good health. As he wrote to the father-general of his order in 1879, “The experience of six years shows me that it was not in vain that I put my health under the protection of the Sacred Hearts”—Jesus and Mary—“so as to be preserved from this terrible contagion that surrounds me.”

There was a dark corollary, though, to the belief that health implied virtue: the belief, widespread in Damien’s day, that illness implied vice. The stigma against leprosy in particular was ancient; as a Protestant named Thomas McClure wrote in the London Tablet, in opposition to Damien’s work, “If you understand the teaching contained in the Bible, you will perceive that leprosy was a prominent mark of God’s displeasure.” A theory then in vogue reinforced the moral diagnosis. Informed medical opinion of the day often linked leprosy to syphilis; some doctors even believed that leprosy was nothing more than end-stage syphilis. (They were wrong; leprosy is today often called Hansen’s disease after the man who discovered its cause, a bacillus to which most people have a natural immunity.) Damien himself was aware of the syphilis theory and didn’t deny it, though he thought a certain minority of cases could be caught by touch or by breathing the same air as the sick.

The fact that Damien’s work was being debated as far as London shows the great reach of his fame. The same week of his arrival on Molokai, a Honolulu paper hailed him as a “Christian hero”; similarly hagiographic reports from around the world soon followed. Damien initially discouraged the news stories—“I want to remain unknown to the world,” he said. Soon, though, he began to see the fund-raising potential of publicity, and he began recommending the book The Lepers of Molokai, Charles Warren Stoddard’s account of the Kalaupapa settlement, in some of his correspondence.

But though popularly revered, not everyone loved Damien—particularly some members of his own order, many of whom were likely jealous of his fame. A rumor even spread among them, at one point, that Damien “was not a pure man in his relations with women.” A colleague of Damien’s, Father Albert Montiton, had made the accusation directly to the priest in 1881, talking to him about it three days in a row. Damien denied the charge.

Molokai coast with a view of the leprosarium in 1907. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Molokai coast with a view of the leprosarium in 1907. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Still, something troubled Damien’s conscience, who felt an urge to regularly make confession. (According to Catholic theology, to die without confessing a mortal sin may jeopardize one’s chances of heaven.) In those years in which the quarantine on Molokai was especially tight, confession was logistically complicated. Like the lone barber in a frontier town, Damien could not perform his services on himself. Yet he could not leave Molokai; nor could another priest enter. One day, a steamship bearing a fellow priest anchored off the shores of Molokai. Damien rowed out to meet his visitor, but was forbidden to board. So Damien called his confession up to his confrere at the top of his voice, the small rowboat pitching beneath him. The steamboat then sailed off, bearing the weight of Damien’s sins with him.

Whatever Damien may have felt the urge to confess, his enduring good health surely was proof of something, he felt. He wrote to his brother Pamphile in 1883:

“Here I am, already 10 years in the service of the plague-stricken without having contracted the disease. The papers this week cite my name to prove that there is no need for alarm at seeing lepers in our small towns, there is no danger of contracting the disease by living near them etc. These gentlemen judge only from what they see on the outside—without understanding that God has a special care for those who devote themselves in his name to the service of the unfortunate.”

Damien did not trouble his brother with any mention of the handful of health problems he had been having: not the occasional skin eruptions, which ointments seemed to keep in check, nor the pain and numbness in his foot, which he put down to rheumatism.

Molokai’s seacliffs viewed from the air. (Photo: David Zax)

At the end of November of 2007, a man came to Honolulu from Rome. Monsignor Robert Sarno, a high-ranking member of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, and its only American, had come to conduct yet another phase of the Vatican’s inquiry. A rumor soon circulated—it reached both Mrs. Toguchi and Dr. Chang—that Monsignor Sarno was “the Devil’s advocate.”

Historically, the Devil’s advocate was a man appointed by the Church to poke holes in an advancing cause for sainthood; the role was officially abolished in Pope John Paul II’s 1983 reforms. In fact, the Brooklyn-bred Monsignor Sarno’s official title was “Instructing Judge,” and his task was to “explain and clarify the supposedly miraculous healing of Audrey Toguchi.” But the rumor was an unsurprising one, as the monsignor later illustrated for a Belgian TV journalist: “Perhaps Audrey called me the Devil’s advocate because that was my attitude, to get at the truth. See, Audrey is convinced she had the miracle…while we can accept that, we have to make sure that is verifiable, that you can actually make that statement. You can think it in your heart, you can feel it, but can you prove it with facts and dates?” All the incessant doubting, all the constant undermining, needling, and deflating traditionally associated with the Devil’s advocate, Monsignor Sarno would now apply to Audrey Toguchi’s supposed miracle.

What had brought the monsignor to Honolulu were not scientific concerns, but theological ones. The story that Mrs. Toguchi had presented at the first tribunal had been simple. “Who did you pray to for this cure?” they had asked her, and she had responded, simply, “Father Damien.” “Mrs. Toguchi, what was the date you went to Kalaupapa?” they asked her, and she said it must have been between the biopsy that proved her tumors and the x-rays that showed them shrinking. For a while, this had been the accepted story—that Mrs. Toguchi had been handed down a death sentence, had swiftly flown to Molokai in her desperation, and had been suddenly and dramatically rescued following her pilgrimage.

Mother Marianne Cope, also known as Saint Marianne of Molokaʻi, in 1883. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Mother Marianne Cope, also known as Saint Marianne of Molokaʻi, in 1883. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But over the course of the investigation, the tribunal discovered a more complicated timeline. Mrs. Toguchi made two visits to Molokai, one in 1997—before she was diagnosed with cancer—and the other in 1999—after the cancer had already disappeared. They could not find her name on the Kalaupapa visitors’ register during the crucial month in 1998 between her dire diagnosis and her first signs of regression. Complicating matters further, Monsignor Sarno had a letter that Mrs. Toguchi had sent to the Pope in 1999, in which she wrote that she had prayed not only to Father Damien but to ten other aspiring saints as well, including Mother Marianne Cope and Mother Theresa. No clinical trial of a drug would be accepted if it turned out the participants had been popping other pills, and possibly not even the experimental one, at the crucial moment. How could the Church deem Damien to have effected Audrey’s cure, if she had appealed to others and potentially not to Damien at all in her time of greatest need?

It was a serious question, and Monsignor Sarno took it seriously. Sarno’s tribunal maintained the tone of an interrogation. When Audrey Toguchi’s sister Velma Horner misremembered the date of a pilgrimage to Molokai, there was nothing gentle in the way Sarno phrased his reply.

“No, that’s not true,” he said. “You went on the pilgrimage September 17, 1997.”

Ms. Horner scrambled to explain what she meant. She began to describe the graveside visit, and Monsignor Sarno cut in.

“Isn’t it possible that she was just a tourist?” he asked. Even the most basic facts of the case were apparently suspect to the monsignor.

“She didn’t go as a tourist,” Ms. Horner protested. “She went for help, to pray for help.”

Sarno was equally tough on the members of clergy. Examining a prayer card that Father Keahi had given to Mrs. Toguchi while ill, he saw a sticker affixed to it that read: “This relic was blessed for You by Fr. Chris Keahi…at the Tomb of Blessed Damien at Molokai, Hawaii.”

“What do you mean by ‘this relic’?” Sarno asked. “There doesn’t seem to be any relic here.” (Strictly defined, a relic would either be a fragment of a saint’s remains or belongings, or something that had been in direct contact with them.)

“It’s just that it touched the grave,” Father Keahi conceded.

On November 26, Monsignor Sarno summoned Audrey Toguchi. Whatever warmth the gentle old aloha-spirited woman exuded when they met did nothing to soften Sarno’s line of inquiry.

“And what does ‘I went to Father Damien’ mean to you?” Sarno asked, parsing a phrase she used.

“It means I went on a pilgrimage to Father Damien—”

“No, no,” he said. “You didn’t until May 1, 1999—”

“And it also meant—”

“—which is months after. On October 2, you said you were going to pray, but you didn’t go to Kalaupapa yet. You said to Dr. Chang on September 3—”

“I said I went to Father Damien,” she said, “and that does not mean physically, and I went to him and I said to him, ‘Please help me.’” When Monsignor Sarno pressed her further, eventually she said, “All I can tell you is that when you are so tied up in all this, all your mind is, Please help me. So all these dates, I can’t even explain it. So when I say I went to Father Damien, it doesn’t mean that I flew back and forth to Kalaupapa.”

By the time Monsignor Sarno interviewed his next witness, any hope of salvaging the original narrative of Audrey Toguchi’s cure—the one that most neatly fit what one would expect a miracle story to be—had been destroyed. “It would seem that the two pilgrimages aren’t directly connected to her cure,” Sarno told the next witness. “We can rule out anything happening on those two trips or as a result of those trips.”

Kalaupapa from the air. (Photo: David Zax)

Months passed, while Hawaii waited for the news. The Sacred Hearts representative in Rome, Father Bruno Benati, kept the world appraised through the order’s website. One day in 2008, he posted what seemed an encouraging schedule:

“June 17th: Cardinals and Bishops will sign the document approving the miracle of Blessed Damien.

“June 30th: The document about the miracle will be presented to Pope Benedict XVI for his approval. We invite you all to be close through prayers.”

But June 17 arrived, and there was no word from Father Benati. He had died that very day, of a massive heart attack, at 66. Hawaiian reporters scrambled for news of the cardinals’ and bishops’ decision, but no one could confirm anything. June 30 came and went, without any sign from the pope.

At last, after a tense wait, Bishop Silva was able to announce in the Hawaii Catholic Herald, “We thank God that on July 3, the Holy Father signed a decree confirming that the healing of Audrey Toguchi from cancer was indeed a miracle performed by God through the intercession of Father Damien.” The doctors had been sufficiently puzzled, the theologians sufficiently reassured. Mrs. Toguchi’s prayers had clearly centered on Damien, even if they weren’t directed exclusively towards him. Weighing the evidence, Monsignor Sarno had concluded that Damien’s intercession caused the miracle, proving he was in heaven—a true saint.

On October 11, 2009, tens of thousands of people came from all over the world to celebrate their favorite of the five men and women who were to be canonized that day. (“We all think Damien had the best curriculum vitae,” said Sister Regina Jenkins of the Sacred Hearts.) A few days before the ceremony, President Obama, a native Hawaiian, issued a statement of praise: “I recall many stories from my youth about his tireless work there to care for those suffering from leprosy who had been cast out…we should draw on the example of Fr. Damien’s resolve in answering the urgent call to heal and care for the sick.”

Prominent among those in the basilica that day were a few of the last remaining Hansen’s disease patients of Kalaupapa (the word “lepers,” deemed hurtful, is confined to historical use). When successful treatment for the disease finally came to Molokai in the mid-20th century, the patients were permitted to leave. But for many, Kalaupapa had become home, and they had chosen to stay. Their numbers are dwindling, though; while the patient population hovered near 1,000 in Damien’s day, today there are fewer than ten full-time residents who once suffered from leprosy on the peninsula, the youngest of whom is 72.

Dr. Chang wore a black suit and blue tie, while Mrs. Toguchi wore a white muumuu and lei of eyelash yarn. When the proper moment came, they climbed to the papal altar and, with Mrs. Toguchi bearing a small relic of Damien’s hair, together walked beneath the massive twisting columns to meet the pope.

Then it was done. Father Damien of Molokai was a saint.

Months later, back in Honolulu, some of the younger doctors still gently rib Dr. Chang about the whole thing. “How’s the pope?” one asked him on a recent visit back to his old hospital, from which he retired a few years ago. “Oh, he’s good,” said Dr. Chang, adding a crack about how he ought to start bottling Dr. Chang’s Holy Water. In other company, though, he sets joking aside. His sons have noticed that their father seems, now that he is in his eighties, more interested in religious questions: about the possibility of a God, about what happens when you die. Now and then, he’ll send out mass emails containing religio-philosophical musings. To friends, to acquaintances—even to the workers who inspect his baggage for soil or sea grapes or pandanus at the Honolulu airport—he’ll tell once more the story of Mrs. Toguchi’s miracle, the canonization of Saint Damien, and the role he played in it all.

As it happened, one such worker at Agricultural Inspection, an older man named Sam Keliiaa, had a daughter who was gravely ill. Dr. Chang asked Mrs. Toguchi in an email if she would pray for her, since Mrs. Toguchi was, he wrote, “closer to the ‘Sources.’

“SHE NEEDS TO THINK POSITIVELY AND PUT HER FULL FAITH IN OUR DEAR LOVING FATHER,” Mrs. Toguchi wrote back. “WE HAVE MANY SAINTS WHO WOULD WILLINGLY PETITION FOR HER CAUSE. MOTHER MARIANNE ALSO NEEDS HER HELP.”

Such sudden fame has not been welcome to Mrs. Toguchi, nor has it been easy to bear the burden of the hopes of so many ill. At the Ergife Hotel in Rome, as with so many rock stars before her, her travel agency checked her in under an assumed name. “Your life is not your own,” she says of celebrity. Father Keahi recently noticed that Mrs. Toguchi no longer answers the phone when in rings, picking up only once she recognizes his voice in the message he begins to leave.

But Audrey Toguchi never claimed to be a saint. “I’m not an important person,” she told the tribunal, when somebody had asked her why she thought she had been chosen. She tried to emphasize that she wasn’t the one who was holy, the one who had a direct line to the divine: “The one that believes in God is Father Damien,” she said.

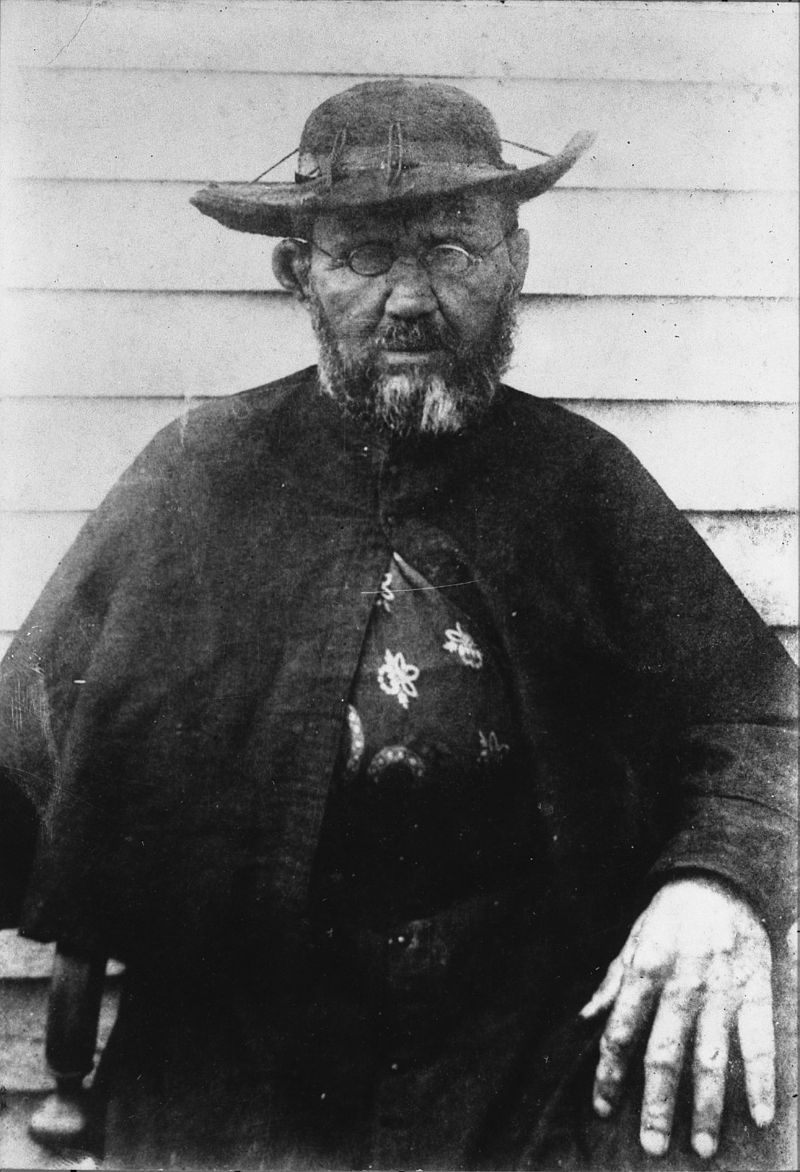

Father Damien in 1889. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

One day in December of 1884, Father Damien sought relief for his tired feet by soaking them in what he thought was warm water. When he withdrew them, he saw they were covered in large, fresh blisters. The skin peeled off. Only then did he realize that the water had been scalding hot.

In August of 1885, Dr. Arthur Mouritz, a settlement doctor, noted “a small leprous tubercule” on Damien’s right earlobe; the disease soon visibly invaded his cheeks and forehead. “My eyebrows are beginning to fall out,” Damien wrote. “Soon, I will be disfigured completely.” He had always begun his sermons on Molokai in fellowship with the words, “We lepers.” Now, literally, “I am a leper,” he wrote.

Though Damien knew he couldn’t hide his condition from the world, he took care with how he presented himself in letters that might appear publicly. “I am calm, resigned, and very happy in the midst of my people. God certainly knows what is best for my sanctification and I gladly repeat: ‘Thy will be done!’” The London Tablet, reprinting the letter, asked, “Where is the heroism that will vie with this?”

By 1887, wrote Dr. Mouritz, “the skin of the abdomen, chest, and back, both extensor and flexor surfaces of the arms and legs showed tubercules, masses of infiltration, deep maculation in varying degrees of extent and severity.” When Damien submitted to a physical, Dr. Mouritz also took the opportunity to examine the priest for signs of any other ailment. Given the rumors that had circulated, and the current theories of contagion, Mouritz examined Damien for any symptoms of syphilis. He found none.

Damien’s nose, lips, forehead, and chin became swollen; his earlobes drooped and dangled towards his collar. His eyes weakened and became enflamed, while sores sprouted on his neck, wrists, and hands. His knuckles grew knobby and ulcerated, as did his knees. In October, he collapsed at the altar while performing mass. “The only way out of here is by the cemetery road,” he wrote Pamphile.

One of the last photographs shows him standing against the slats of a house he likely built himself. A worn black cape is buttoned at the neck; the upturned ends of the brim of his dusty black hat are each tied to the crown with bits of string. The lenses of his thin wire-rim glasses obscure his pupils. His thick beard is dark at the sides, with a full shock of white at the chin. His forehead, his ears, and his swollen hand are so marked with tubercles as to give his skin the look of boiling water.

The reports that came next had the easy sheen of hagiography. On April 15, he died “with a smile,” reported a witness from his order, “like a child going to sleep.” One of Mother Marianne’s nuns, Sister Leopoldina Burns, described a calm face from which “every trace of leprosy” had disappeared: “one could so plainly see that his pure soul was enjoying the home of the Sacred Heart that he had loved so dearly.” They buried him beneath the pandanus tree, where a madeira vine had blossomed, Leopoldina wrote, “with downey white flowers that had filled the air with sweet perfume.” Reports like these soon traveled round the world.

Such was the story of Damien’s death the reading public was granted in 1889: a stoic death, a long-expected and a good one, softened and sweetened by the certainty of a homecoming so long desired.

But in biography, as in other fields of inquiry, knowledge accrues over time.

When Dr. Mouritz published some decades later his history of leprosy in the Hawaiian islands, he emphasized that Damien had not always accepted his illness with calm resignation. In 1887, wrote Mouritz, Damien had become fanatically devoted to an experimental hot bath treatment from a Japanese doctor named Goto. The treatment had the effect of further emaciating Damien and causing him to totter when he walked, but only after many months did Damien finally give up “all hope of getting any relief or stay of his leprosy,” wrote Mouritz, “and permanent gloom settled down upon him.” The doctor sometimes found Damien completely still and silent, staring off into the distance.

In those last years, Damien’s urge to make confession became more pronounced. And while Hawaii’s Board of Health had relaxed the quarantine rules for non-patients, making the steamship confession a thing of the past, the priest was now himself a patient, and the rules of quarantine applied even to him. For a man who spoke so often of the “narrow way” to heaven, a man who had written notes reminding himself of the consequences of “the least infraction” and of the need to constantly “watch over my vile self,” regular confession was essential. “I beg of you, let some one descend into my tomb once a month to hear my confession!” he wrote his superior, Father Leonor. Sometimes Damien’s soul was so heavy that he blurted his confession to a statue of the Virgin Mary in his church.

In 1886, Damien pleaded with Father Leonor to let him make a trip to Honolulu. Leonor rebuked him, writing that such a trip could plunge the Honolulu mission into quarantine. “Your intentions prove to us that you possess neither delicacy nor charity towards your neighbor,” wrote Leonor, “and that you think only of yourself.”

These words could not have come at a worse moment, since one of the most bizarre and improbable symptoms Damien presented with in his final sickness was what Dr. Mouritz referred to as “Melancholia Religiosa,” or “the delusion of his being unworthy of heaven.” The doctor added, “This was most remarkable, for if there was any man in the universe who had every prospect of future happiness and salvation, that man was Damien.”

But his superior’s harsh letter confirmed Damien’s self-doubt. After all, why would God have allowed his body to continue to grow leprous, if his soul had been pure? “I still await Our Lord, through the intercession of our good Mother, to perform a miracle in my favor,” Damien wrote, “but alas, I am not worthy.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook