How Aboriginal Hunting and ‘Cool Burns’ Prevent Australian Wildfires

The current crisis has pushed the country to consider cultural burning.

There is a scar across Australia’s Western Desert. For millennia—no one is sure how many, though evidence of Aboriginal people’s presence in Australia stretches back 50,000 years—the Martu people used fire to hunt in the scraggly bush. In a practice called cultural burning, they set low blazes patient enough for small animals such as bettongs and wallabies to flee their burrows before the fire reached them. Years of cultural burning cleared underbrush, creating a patchy habitat preferred by the small animals Martu people most liked to hunt, while simultaneously preventing massive lightning fires from consuming the land.

For the Martu, these fires were so vital that they were a means of maintaining life itself. “They would say, ‘If we weren’t out here burning, things won’t exist,’” says Rebecca Bliege Bird, a Pennsylvania State anthropologist who has worked with the Martu for decades.

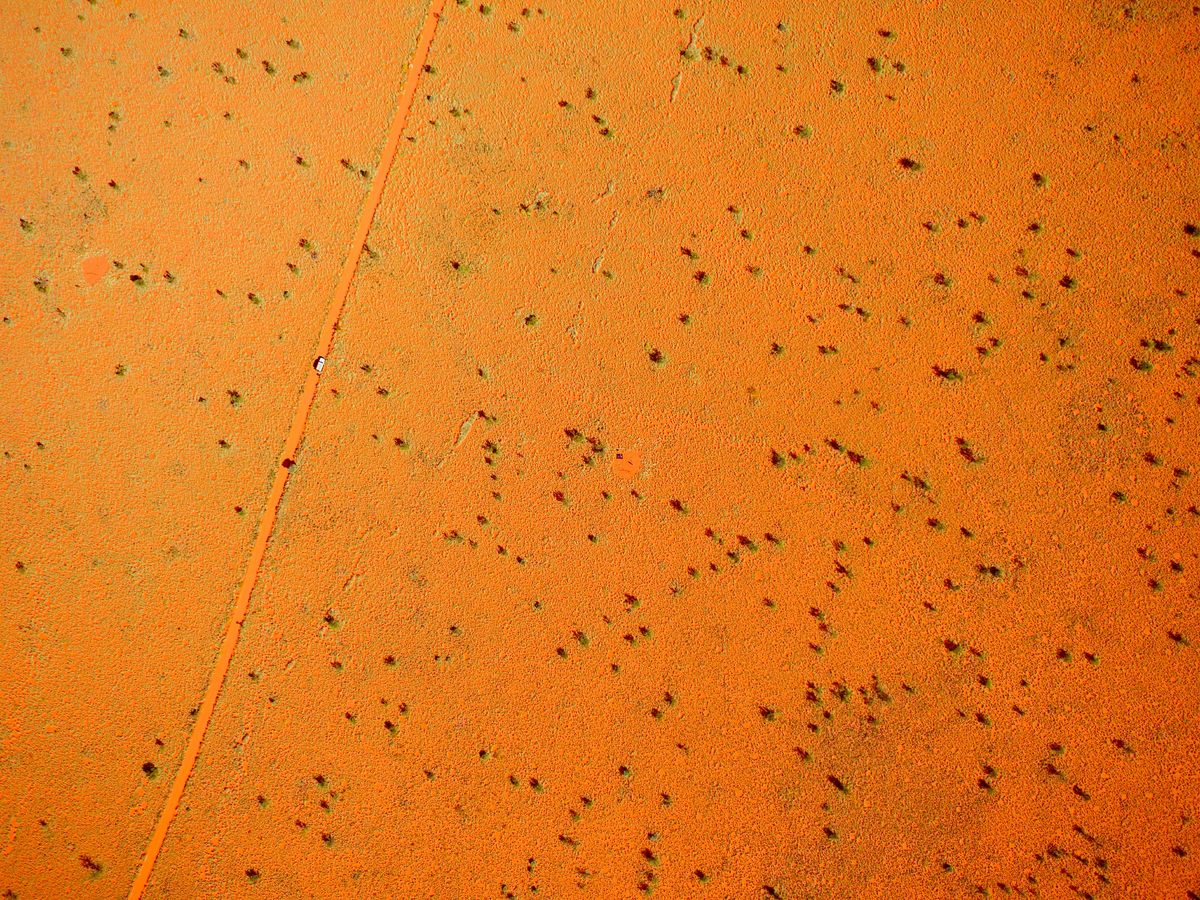

But when, in the 1960s, the Australian government pushed Martu people into towns, in order to test missiles on their land, the life-giving burns stopped. Lightning fires—large, hot, unscrupulous—took their place. In the 20 years it took the Martu to regain access to their homeland, the entire ecosystem was knocked off balance. The lightning burns disrupted plant and animal habitats. An influx of invasive cats helped drive 10 species of small mammal to extinction. The land bears the memory of this imbalance: From the air, areas the Martu have burned are stubbly and patchwork, an intricate barbershop coiffure. In contrast, wide swathes of lightning-burned country are raw as a skinned knee.

This pattern is typical of much of Australia’s landscape, where, in many regions of the country, Aboriginal people have used fire to hunt and maintain ecosystems for millennia. Centuries of Euro-Australian suppression of Aboriginal people, and of cultural burning, have exacerbated ecosystem degradation, leaving the contemporary landscape “really sick,” says Oliver Costello, a member of the Bundjalung Aboriginal community from New South Wales, who co-founded Firesticks, a cultural burning organization.

In the past few years, researchers such as Bliege Bird have published evidence affirming what Aboriginal people already knew. In recent studies, Bliege Bird and her co-researchers, Stefani Crabtree and Douglas Bird, drew on years of interviews and experience with Martu hunters in order to model and measure the effect of their exile on the area’s food web. They found that the Martu people’s burning reduced the intensity of lightning fires and, thanks to the creation of patchy habitats, boosted the populations of monitor lizards, dingoes, and kangaroos—all animals pursued by Martu hunters.

The findings affirm a newer thread in the anthropology of North America and Australia, which reevaluates the assumption that non-farming indigenous people have little impact on the landscape. Instead, these anthropologists argue that indigenous people have long altered landscapes on a vast scale and to productive ends: They created America’s rolling prairies and the bumper crops of bison they fostered, and turned Western Australia into a patchwork quilt of burn zones with thriving small-animal populations. On both continents, fire was their primary tool.

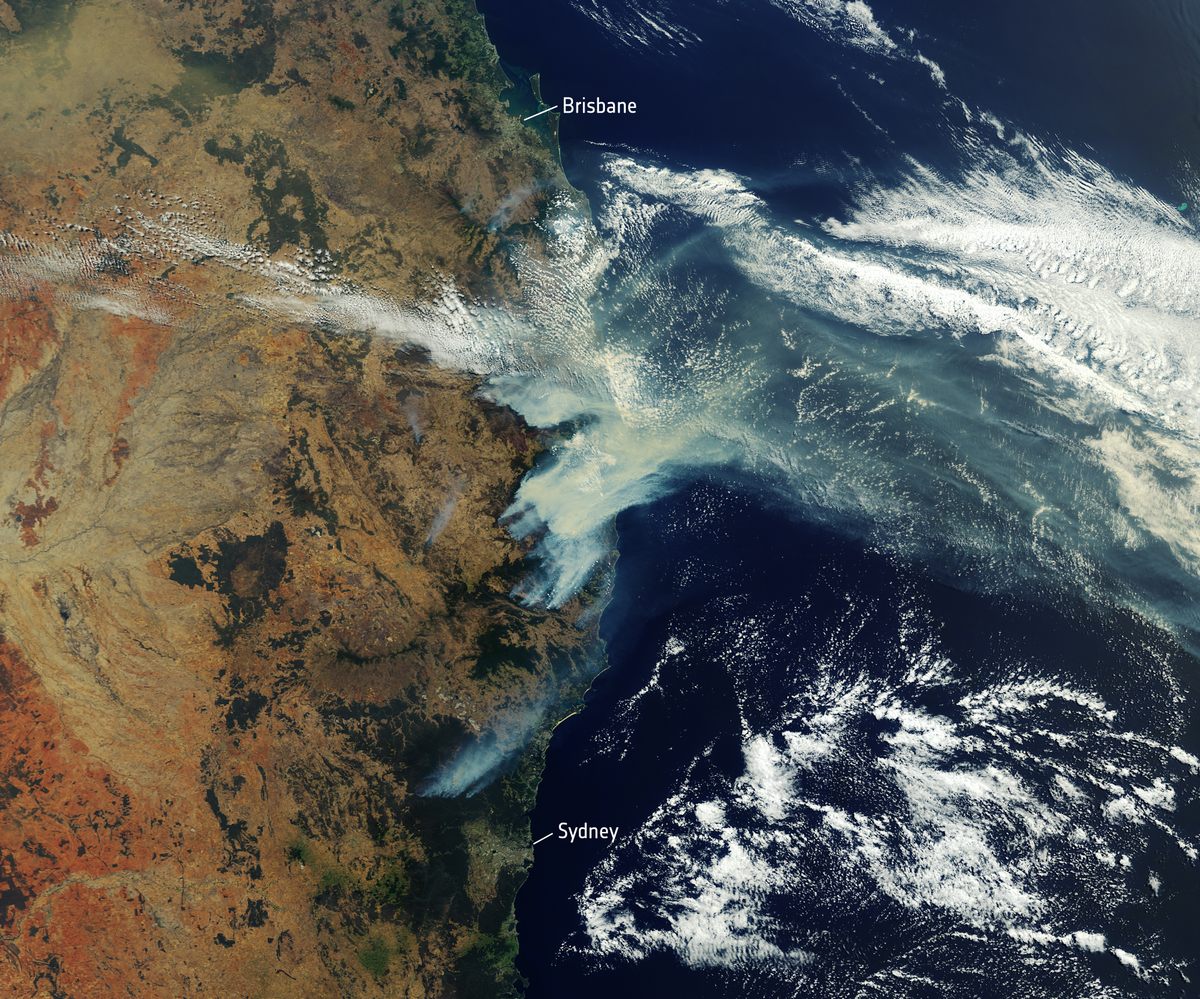

As wildfires grow increasingly destructive—California’s 2018 Camp Fire destroyed 11,000 homes, and an estimated one billion animals have died in Australian wildfires since late 2019—environmentalists and government authorities have turned to these practices for a potential solution. For the past several centuries, the Australian government, like its U.S. counterpart, has pursued a policy of fire suppression, eliminating small periodic fires caused by human intervention and lightning. But these milder fires clear the land of brush and other fuel. Without the fires, parched, kindling-littered terrains are more likely to erupt in wider-scale, destructive blazes. So researchers and fire officials are looking to the original stewards of the land for inspiration: indigenous practitioners of cultural burning.

For Costello, the renewed interest in cultural burning is welcome, but late. “Traditional custodians all over Australia have been saying this for hundreds of years,” says Costello. “It’s only the last few weeks that people have been calling me.” That’s because fire suppression has been part of European colonialism since the first settlements.

Europeans encountered fire as soon as they reached Australia. When Captain James Cook first sailed along the continent’s coast in 1770, his crew spotted smoke, recording the finding in their ship’s log as proof that the continent was inhabited. Early settlers viewed fire as a threat. They were farmers, factory laborers, and seafarers, unused to the continent’s broad blue skies and arid, smoke-crisp landscape. Unwilling or unable to perceive cultural burning as a landscape-management practice, they argued that Australian land was not being put to productive use, and thus was ripe for the taking—a legal justification for settler colonialism that Australian courts upheld as recently as 1982.

From 1794 to at least 1920, Australian colonists displaced, dispossessed, and murdered tens of thousands of Aboriginal people in state-sanctioned massacres. They turned collectively owned Aboriginal land into livestock enclosures, and forbade cultural burning. It wasn’t until 1992 that the first Aboriginal Australians regained rights to heritage lands. By that time, many traditional ecosystems had long since been disrupted.

The scars of that trauma are still burned into Australia’s land, in the bare swathes exposed by devastating lightning fires. And they are burned into the psyches of Aboriginal people, who, as a result of centuries of violence, have more than triple the unemployment rate, double the suicide rate, and a 10-year-lower life expectancy than non-Aboriginal Australians—glaring inequality in a country that has one of the highest human development rankings in the world. This material marginality goes hand in hand with the spiritual trauma of being separated from traditional lands and ways of life. “I try to stay happy,” Costello says. “But it doesn’t mean I don’t see what’s happening and don’t feel the pain.”

For Costello, healing came through fire. He first experienced cultural burning as a young person in the Blue Mountains. But it wasn’t until Costello met Victor Steffensen, a long-time advocate of the practice, that his passion really ignited. Steffensen talked about land stewardship, about fire as a community-led practice, and a chance for Aboriginal people to reconnect with their country and each other. Lightning struck. “‘Oh, wow!’” Costello thought. He’s been burning the land, and passing on his knowledge, ever since.

When Costello talks about fire, you soon realize his relationship to it is fundamentally different from that of most urban people. For most non-indigenous, urban, and even agricultural people, fire is a destructive force, anti-civilizational and apocalyptic. The history of famous Western fires is, after all, a catalogue of destruction: London in 1666; San Francisco in 1906; hell itself.

But when Costello talks about cultural burning, it is with gentleness, the way you might talk about a bubbling brook. Burning the landscape first requires knowing it, he says; a good cultural burner will understand the land’s history, its humidity, its colonies of kangaroos and birds. Unlike fire department-conducted hazard-reduction burns, which are pre-planned and involve burning wide swathes of land simultaneously, practitioners light cultural fires in small areas on foot, with matches or, traditionally, with fire sticks, two fibrous sticks rubbed together to spark and hold flame. The flame begins slowly, almost sweetly.

“The fire will trickle around the grass and the leaves,” says Costello. “It’ll be this nice, white smoke in the air.” It won’t touch the tree canopy, allowing leaf coverage to remain constant, and it hisses across the ground slowly enough that animals have time to escape.

Aboriginal groups use fire in different ways. For many, including the Martu, cultural burning is a traditional part of hunting. Martu hunters set fire to clear patches of land, revealing animals’ burrows. The patchy landscape left by repeated burns creates diverse habitats perfect for local creatures, and the burns maintain a relationship between humans and other species.

In these lands, fire is a language that outsiders rarely speak. When she first moved to Martu country, says Bliege Bird, burned earth irked her. It looked sandpaper-rough as a bad haircut. After a few years with Martu people, however, those patches began looking different. “Look at the burn area,” Bliege Bird found herself thinking. “It’s so safe and clean.”

It’s a shift in consciousness many Australians are now experiencing. Since the fires started in December, Costello has found himself at the receiving end of a tidal wave of calls. Homeowners ask how they can protect their land; locals request workshops; international media send interview requests. With so much life already lost, the attention has Costello feeling both rueful and giddy. Neither Aboriginal people, nor their country, would be in this situation if Europeans had respected Aboriginal people in the first place.

Still, there is hope in this moment of reckoning. Costello cites Bliege Bird’s research as proof that science is catching up to traditional knowledge. Meanwhile, fire departments are unveiling programs that integrate cultural burning. While the legacy of European violence still aches, Costello is adamant that cultural burning is a team effort. “I’ve only learned a drop in the ocean,” says Costello. “But when you put all the people together, there’s buckets and buckets of knowledge.” That knowledge can build into a stream—or, perhaps, a tongue of fire, satisfying the land’s thirst to burn.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook