The Scandalous Life of Nurse and Adventurer Kate Marsden

She spent 11 months trekking to Siberia to find a cure for leprosy, but her love life overshadowed everything.

The Russian village of Sosnovka, in the Sakha Republic, is not the sort of place that a person travels to on a whim. The republic is part of Russia’s Far Eastern Federal District, which, at 2,382,000 square miles, is nearly the size of India. Across that gigantic area live about 6.3 million people, fewer than in the city of Changsha, China. Though the highway that leads to Sosnovka from Yakutsk, the provincial capital, is being upgraded, not long ago that stretch of more than 300 miles was a dirt road that might take an entire day to traverse.

If you reach remote Sosnovka, though, you will find a small museum and a monument, erected in 2014, to a nurse from England named Kate Marsden, who went there in 1891. Back then, her journey took months. On the final leg, from Yakutsk, Marsden rode a horse across the boggy taiga, dodging bears and clouds of mosquitos for seemingly endless days until she reached her destination.

In many ways, Marsden fits the profile of a daring female explorer of the Victorian age. She went to Siberia to find a particular medicinal herb that she thought could cure leprosy, and to meet sufferers of the disease living in the Russian forest. Her advocacy for leprosy patients has since made her a local hero—there’s even a very large diamond named after her—but in her own time, her adventurousness, coupled with gossip about her personal life and sexual preference, brought her only infamy. After she returned from Siberia, she was vilified as a fabulist and an embezzler who had betrayed people who trusted her. Her critics questioned her motives for going to Sosnovka at all: What was she really after? Or was she just running away from something?

Marsden first heard of the miracle herb, which might alleviate the symptoms of leprosy and perhaps even cure it, from a doctor in Constantinople. It grows only in Siberia, he told her. In the late 19th century, that vast region had been under Russian control for almost two centuries, but it was a place of exile, disconnected from the rest of the country. Construction on the Trans-Siberian Railway did not start until the next year, in 1891.

None of this diminished Marsden’s obsession with the herb. “Had it been Kamchatka or the North Pole I would have tried to reach it,” she later wrote. She had been concerned with the plight of leprosy patients since 1877, when she first encountered the disease in Bulgaria, while nursing soldiers wounded in the Russo-Turkish War. By the 1880s she was pleading for permission to visit Molokai, the Hawaiian island leprosy colony, and was obsessed with meeting Louis Pasteur, who she thought had developed a leprosy vaccine. In February 1891, after no less an authority than the Empress of Russia corroborated the existence of this leprosy-curing herb, Marsden and a Russian-speaking friend, Ada Field, set out for Siberia.

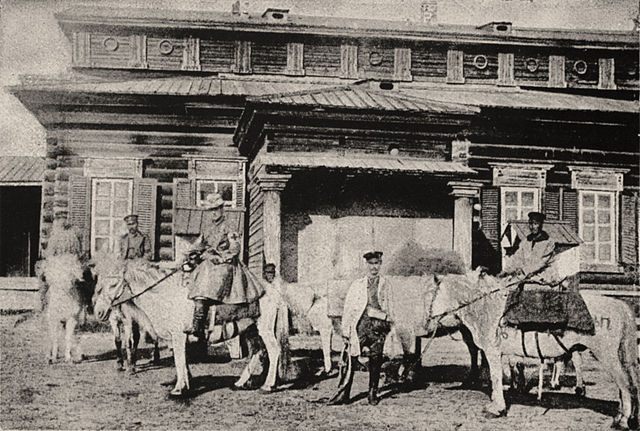

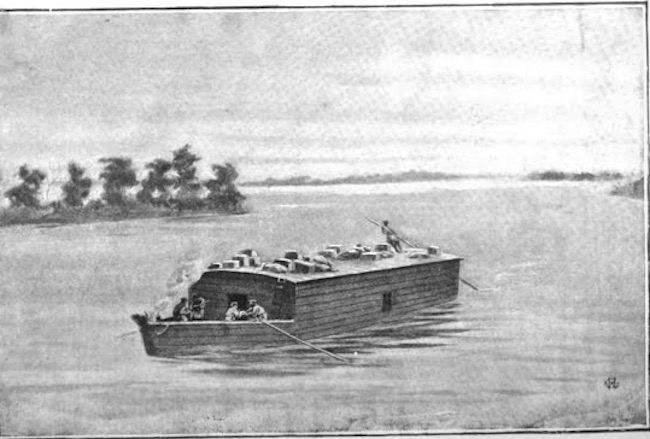

Marsden and Field traveled first by train, then by sledge, “bump, jolt, bump, jolt—over huge frozen lumps of snow and into holes” to Omsk, in southwest Siberia. From there, Marsden continued alone. A horse-drawn carriage took her to the River Lena, a barge took her to Yakutsk, and from there she continued on horse, riding astride like a man. The road was so bumpy and muddy that she had no other choice. The journey, though difficult, had its fascinations. Marsden visited villas and prisons, saw eagles and forests where hundreds of trees had fallen (witches, the locals told her), learned that milk could be sold in frozen blocks, and rode across a stretch of taiga where the peat and forest were bright with flames. “The whole earth for miles around seemed full of little flickers of fire … rising here and there above the earth,” she wrote.

After months of traveling, Marsden finally reached her destination, the area around Sosnovka, where she could see firsthand the conditions in which leprosy patients lived. They had been exiled there from their communities to small, overcrowded huts, without good clothes and often short of food. She met a 14-year-old boy who snuck back into town at night to sleep in his mother’s house, an uninfected girl born in an exile village and barred from leaving, a woman whose only companion, another patient, had gone crazy.

Having collected these stories, Marsden turned around and started the long journey back to Moscow. Her expedition lasted 11 months in total. Upon her return, she announced that she would write a book of her journey, to raise money for the suffering people she had met. She also, she said, brought back samples of the herb she had sought. In the ensuing months, Marsden was celebrated by Russian royalty, sought after by the press, and named one of the first female fellows of the Royal Geographic Society. Soon, though, the social intrigue of her past returned to spoil her newfound fame.

Of the women who had formed close relationships with Marsden, Ellen Hewett was most to blame for the scandal that dogged her after Siberia. The two women met while sailing to Europe from New Zealand, where Marsden lived for five years, and they became close. Hewett, an older woman, was “drawn to Marsden,” as University of Oxford scholar Elizabeth Baigent recounts in her Marsden biography, and after they landed, the pair continued to travel together around Europe, with Hewett paying the way.

“It was only when her finances reached a perilous state that Ellen Hewett was forced to accept the motives behind Marsden’s avowed affection for her,” writes Hilary Chapman in the New Zealand Slavonic Journal. Marsden needed the older woman’s money to support her peripatetic lifestyle. When Hewett began to understand this, they fought. In a last straw, Marsden struck Hewett, and the women separated for good soon after.

Hewett returned to New Zealand, and tried to warn other people connected to Marsden about the way she had been mistreated. Hewett collected information about Marsden’s other alleged financial scams. She failed to repay loans, sold furniture for a friend who’d left New Zealand and never handed over the money, and committed insurance fraud—taking out two policies before a mysterious accident put her out of her nursing job for months. Even the leprosy advocacy, Hewett believed, was part of the hustle.

The accusations made their way to Isabel Hapgood, an American writer with expertise in Russia. Hapgood had already heard disgruntled rumblings from contacts in Russia, and she chose to make Marsden her enemy. She spent six years working “to bring down Marsden and keep her down,” Baigent writes, by using all of her influence to discredit Marsden’s account of her trip. In a review of Marsden’s book, for instance, Hapgood wrote that it was “absolutely devoid of literary merit” and misrepresented both the conditions of life in Russia and the plight of people with leprosy. The Russian government, according to Hapgood, could care for “the sixty-six leperes over whom this disproportionate fuss and self-advertisement has been wasted.” The real purpose of Marsden’s work, Hapgood insinuated, was financial gain.

It’s not entirely clear why Hapgood had such animus toward Marsden, but her campaign worked. Soon Marsden’s charitable work was under investigation by the Charity Organization Society of London, and wealthy patrons began to withdraw support. A commission in Russia also began investigating Marsden, and almost as soon as she became famous for her long journey, Marsden’s reputation began to tarnish.

In the assessment of her most thorough biographers, including Chapman and Baigent, the accusations against Marsden weren’t entirely unwarranted. She was bad at managing money—though no one found any true irregularities in her charitable efforts—and she was hard to get along with. She could be particularly cruel to women with whom she’d once been very close, as Hewett experienced.

The herb she brought back from Siberia, too, proved to be a red herring. Modern writers retracing Marsden’s journey found that there was a Siberian herb, kutchutka, that was known in the later 19th century as a potential treatment for the symptoms of leprosy. But it was no secret; Russians and Europeans had tested it and found its curative properties wanting. Chemist and Druggist magazine offered to attempt to identify the herb Marsden reported to have found, but she wouldn’t share a sample—even with these experts in medicinal herbs—and soon stopped replying to their inquiries.

The committees investigating Marsden were unable to find any true improprieties in the finances of her Siberia trip or subsequent charity work. Instead, the authorities chose to sanction her for the disclosures about her personal life—specifically that some of her relationships with women had been sexual. Marsden herself confirmed that this was true, although she claimed she was never the initiator. That, in the end, was what sealed her fall from the public eye. Being a lesbian was the worse offense.

In the years after her Siberian adventure, Marsden tried to resurrect her reputation, but she eventually faded from public life. She lived out her later years with her two sisters; she was particularly close with one of them, who helped support her. In the past 20 years or so, historians have assembled a fuller picture of the campaign against her and the accusations that brought her down. If Marsden was difficult, she was also living in a way that few women of her time tried to. The smear to her reputation was as much about prejudice toward women in general and anxiety about lesbian relationships as it was about her own shortcomings. Ultimately, Chemist and Druggist’s 19th-century assessment of Marsden may have been exactly correct: “The fact that her expedition was quixotic in its conception and has been barren of therapeutic results is no reason to carp at the credit to which her bravery and tenacity entitle her.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook