The Dramatic Courtroom Demo Designed to Expose Arsenic Murders

The Marsh test involved fire, mirrors, and collective gasps.

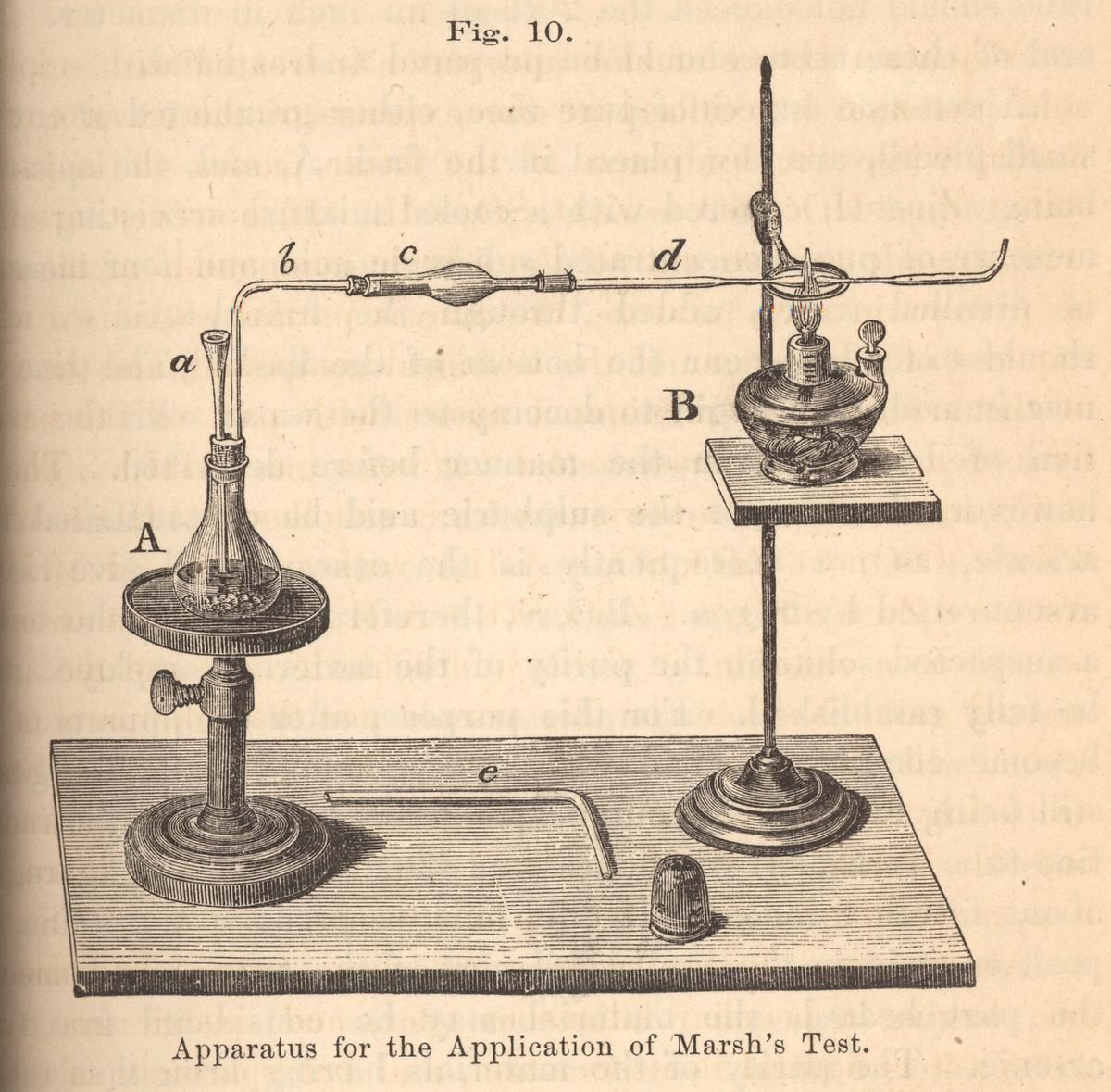

In the premiere episode of the FX series Taboo the protagonist, James Delaney (Tom Hardy), takes advantage of a local doctor’s moral flexibility to quietly exhume his father’s body and determine the cause of death, which he believes to be decidedly unnatural. In a dark operating theater, the surgeon grimly slices into the dead man’s stomach and tests its contents in an arcane maze of glassware and burners. When the apparatus breathes out a metallic residue, Delaney has his answer: his father’s death—and the madness that preceded it—was the result of arsenic poisoning.

Dramatic though it is, this procedure is no showrunner’s invention: known as the Marsh test, the “terror of poisoners” was an important—and much debated—part of 19th-century courtroom drama. (Taboo’s portrayal is mostly accurate, but anachronistic—the show is set in 1814, while the test dates to 1836.) Used well into the 20th century, the Marsh test was for decades the center of ongoing dialogue between law and science, begging questions about the credibility of scientific testing and creating a role for expert testimony in criminal prosecution.

Arsenic is perhaps history’s most prolific poison, and for good reason: it has been historically easy to obtain, is odorless and tasteless, can be introduced quietly over time in small unassuming doses, and in the end its symptoms mimic those of any number of ordinary diseases. For most of history there was no reliable way to detect it, and so arsenic was a lurking threat, with deaths both common and under-reported.

The 1833 murder trial of John Bodle presented a typical narrative of family tiffs gone south: Bodle was arrested on suspicion of slipping poison into his grandfather’s coffee, and chemist James Marsh was called upon to provide forensic evidence at trial. While Marsh found arsenic in the coffee based on then-standard testing, his results were insufficient to persuade the jury; at the time, test results often deteriorated before they could be demonstrated, putting scientists into “take my word for it” territory. Frustrated over Bodle’s acquittal, Marsh went searching for a more reliable test to cut through the ambiguities of arsenic poisoning.

He knew from documented 18th-century chemical processes that arsenic acid would react with zinc to produce arsine gas, and in 1836 figured out that the gas, when heated to a particular temperature range, would leave a stable film of metallic arsenic on a piece of glass or porcelain—an indicator that came to be called the “arsenic mirror.” Marsh’s test could accurately detect minute quantities of the poison and, to the delight of criminal prosecutors, was viable on long-dead bodies. The telltale mirror, further, made for a conveniently clear and dramatic presentation in the courtroom.

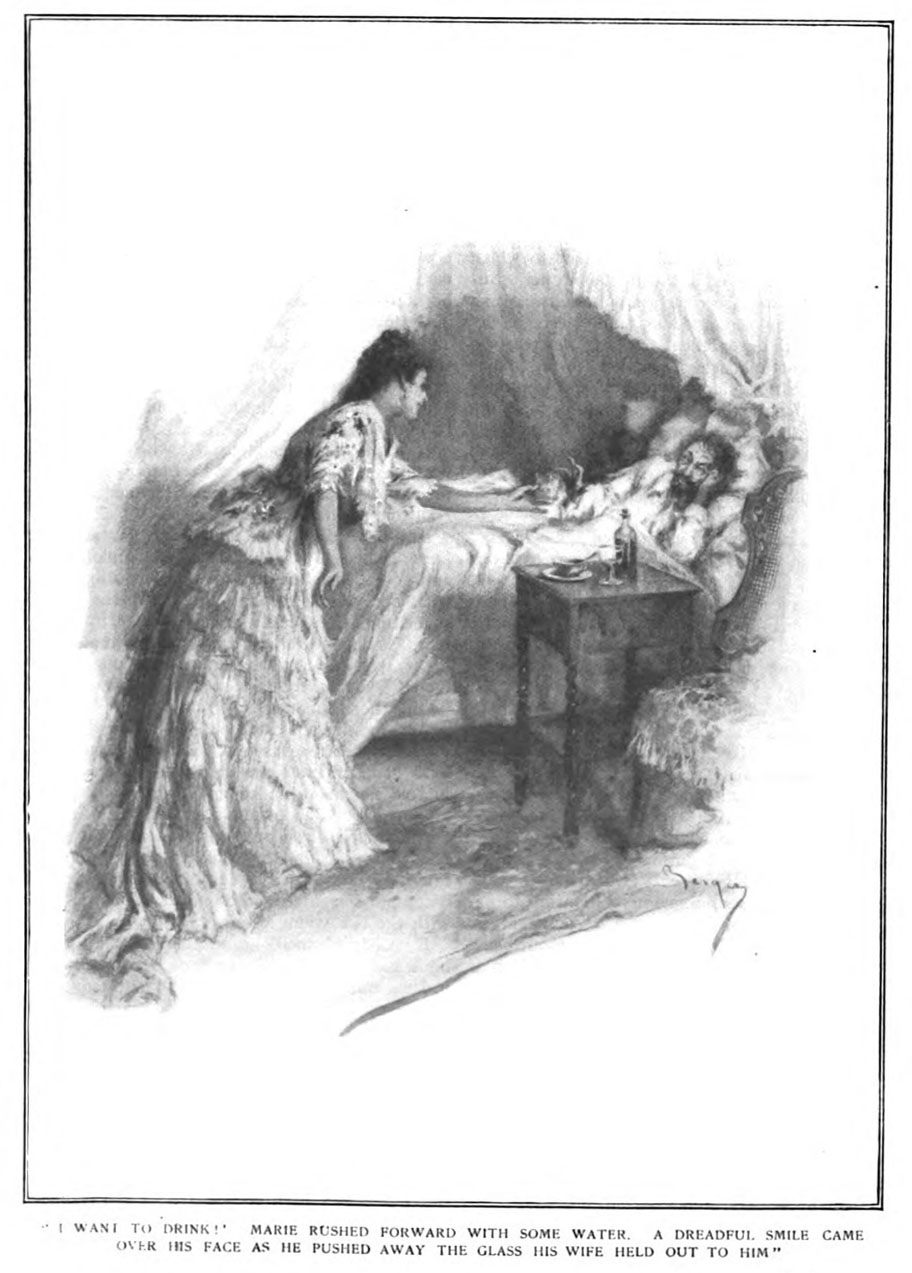

Perhaps the most famous use of Marsh’s test was in the trial of Marie Lafarge in 1840, in which the defendant stood accused of poisoning her husband. Young Marie had entered an arranged marriage with Charles Lafarge believing him to be a wealthy, cultured businessman, and when she found out he was in fact a boorish clod with a run-down chateau, rough sexual habits and substantial debt, she got to putting arsenic in his food. (Friends mentioned that they’d heard her asking casually about mourning fashions: How long did you have to wear black, again?) By the time Charles came to realize his wife’s devotion to home cooking was not a loving gesture, it was too late.

A back-and-forth festival of forensic testing ensued: local scientists first analyzed the dead man’s beverages, stomach tissue and vomit; and while they claimed to have found arsenic, their glassware broke during testing. Moreover, defense counsel was upset at use of outdated techniques, and called in Mateu Orfila, dean of the Paris Faculty of Medicine and the era’s premier toxicologist, who confirmed that only the Marsh test would be credible in court.

Subsequent analysis with Marsh’s procedure failed to find any arsenic, but now it was the prosecution’s turn to call Orfila to their side: citing the scientist’s research stating the stomach might be able to expel poison, they said testing would have to be done on Lafarge’s organ tissue for a truly definitive result.

At this point there was next to nothing left of poor Charles Lafarge, whose body when exhumed was said to resemble a “species of paste, rather than flesh.” While this did not keep the scientists from their work, it did, however, influence the concessions available to a crowd of eager spectators: between entertainment seekers, scientists, lawyers and Marie Lafarge’s surprisingly large fan club, many of whom found the “black widow” thing particularly sexy, the crowd purchased some 500 bottles of smelling salts.

Lafarge’s attorney “wept tears of triumph” when analysis came up clear. Still unconvinced, the prosecution raised the specter of user error: it was the first time the local scientists had performed the notoriously finicky Marsh test. What if they in their inexperience had achieved a false result? To surmount the burden of proof, Orfila himself performed a final analysis. He handily detected arsenic in a milkshake-like preparation of organ mash, and Marie Lafarge was convicted and sentenced to hard labor.

The Marsh test was to have been a decisive tool in poisoning cases, all but eliminating the need for discussion at trial; and yet, the Lafarge trial only highlighted its many vulnerabilities.

As events show, the test was simple but not easy: scientists needed skill and familiarity to get it right. Further, Marsh’s sensitive process raised questions of whether forensic testing invited errant criminal liability around a substance that was both common and legal in the 19th century. Arsenic was an ordinary means of pest control, a routine preservative and household ingredient in things like green fabric dye and wallpaper, and this is not to mention the fact that arsenic made its way into loopy patent medicines and, through coal smoke, much of the atmosphere. Orfila and others for a time (incorrectly) assumed that some measure of “normal arsenic” occurred naturally in the skeletons of living things, absorbed from the environment—the idea being that you could basically boil knuckle bones for beef broth and find trace arsenic in the pot. How were juries to distinguish malice from nature?

And while the test could not be interrogated, the expert could. Used to bolster or discredit a lawyer’s agenda when useful, 19th-century forensic analysis raised questions we still endeavor to answer in courtrooms today: in matters of law and science, how do you tell a good expert from a bad one? Whom do you believe, and why? What causes emotions to cloud over data? What margin of error in conviction, if any, is acceptable in the pursuit of justice?

Courts today apply tests to determine the sufficiency of scientific evidence, admitting expert testimony when it is both relevant and reliable for the jury in its role as trier of fact. In the Marsh era, courts were exploring these issues in real time as new scientific processes came to light.

The Marsh test alone could not answer these questions. What it did do, through the Lafarge case, was to give expert scientists a previously unconsidered role in jury trial. No longer content to leave conclusive analysis to whoever was the local doctor or enthusiast, courts came to seek and rely upon the expertise of qualified professional scientists, applied to accepted techniques and common conditions. In the end, James Marsh did more than put arsenic poisoning decisively out of fashion: he created the lineage of modern forensic science in court.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook