It Was Once Someone’s Job to Chat With the King While He Used the Toilet

“Groom of the Stool” could be a crappy role, but it came with great benefits.

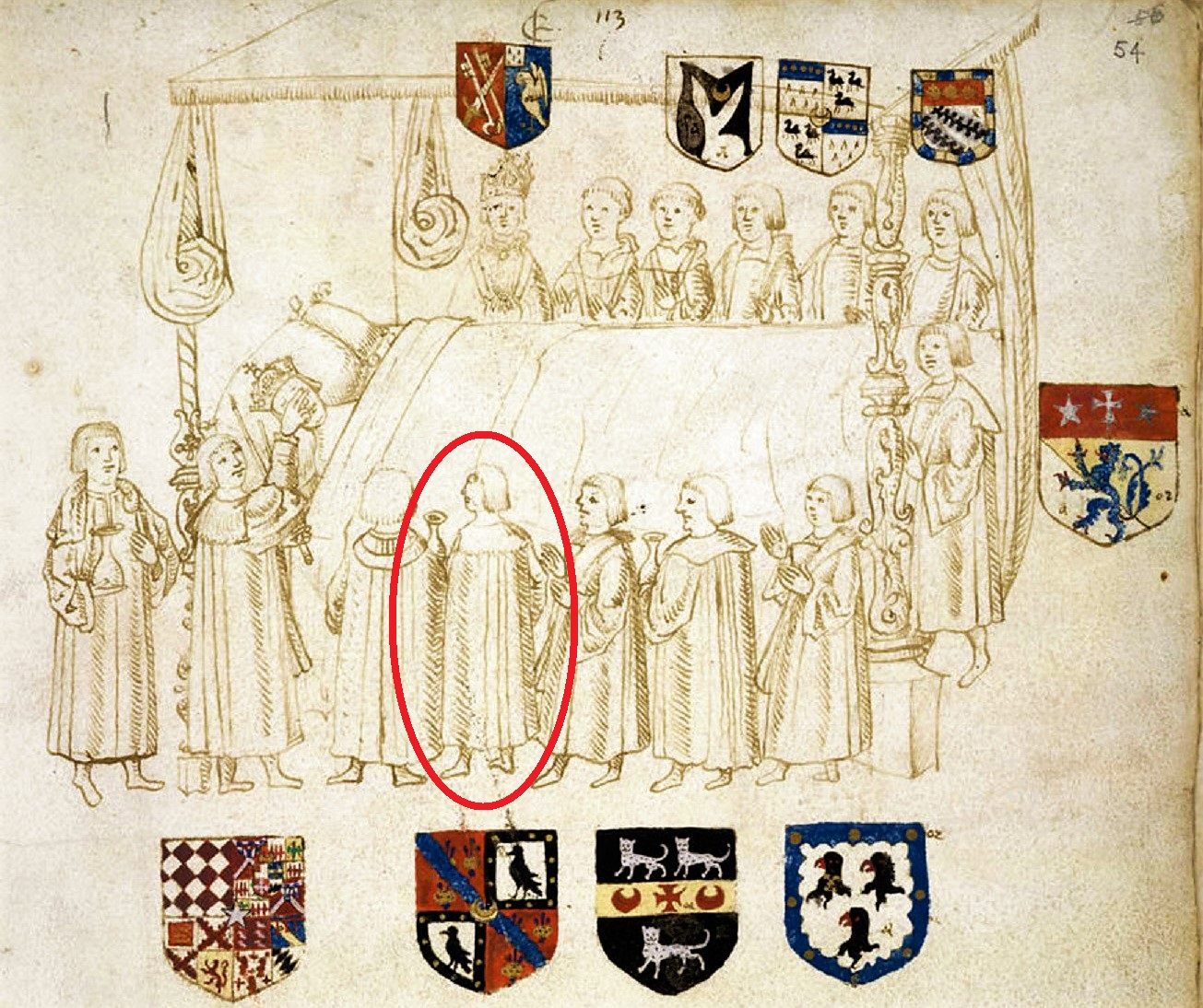

In the 1500s, the King of England’s toilet was luxurious: a velvet-cushioned, portable seat called a close-stool, below which sat a pewter chamber pot enclosed in a wooden box. Even the king had one duty that needed attending to every day, of course, but you can bet he wasn’t going to do it on his own. From the 1500s into the 1700s, British kings appointed lucky nobles the strangely prestigious chance to perform the king’s most private task of the day, as the Groom of the Stool.

This is not the glamorous job you normally would imagine in a palace, but being Groom of the Stool—named for the close stool, the king’s 16th-century toilet—was actually a highly coveted position in the royal house. Every day, as the king sat on his padded, velvet-covered close stool, he revealed secrets. He asked for counsel, and could even hear of the personal and political woes of his personal groom, and offer to help.

The job likely began as a rather less prestigious position. In The Private Lives of the Tudors, Tracy Borman quoted the earliest mentions of the job: a written order from 1497 for Hugh Denys, “our Groom of the Stool,” which included “black velvet and fringed with silk, two pewter basins and four broad yards of tawny cloth” for him to construct a close stool. Borman also points to instructions from 1452 in the Book of Nurture for “The office off a chamburlayne,” which included a little rhyme to help new grooms to the task:

See the privy-house for easement be fair, sweet, and clean;

And that the boards thereupon be covered with cloth fair in green;

And the hole himself, look there no board be seen;

Thereon a fair cushion, the ordure no man to vex.

Look there be blanket, cotton, or linen to wipe the nether end,

And ever he calls, wait ready and prompt,

Basin and ewer, and on your shoulder a towel.

During the reign of Henry VIII in the 1500s, the king’s closest men of court were given the title, often as a group. Prestigious gentry and noblemen hung out with the monarch in his privy room, acting as his personal secretaries with his undivided attention while he sat on his close stool. Later kings appointed one person to the task, who would travel with the king and his portable stool if he went on a journey. Only monarchs in exile were denied a Groom of the Stool, though they did get grooms who helped with the general bedchamber.

The Groom of the Stool was in charge of all the activities and affairs of the king’s bedchamber and other private rooms; making sure the king was well-dressed and bathed, his bed was made, and even that his personal finances were in order. Borman wrote that sometimes the grooms had control to spend cash. Before private rooms and privacy became associated with actually being alone, monarchs were surrounded by servants and attendants at all hours of the day, often sleeping in the same room as attendants. Some kings kept their close stool in “more private” rooms than others, but even private rooms would allow a handful of people, with the Groom of the Stool always among them.

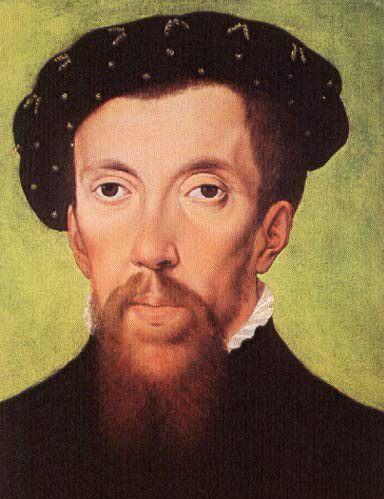

Grooms of the Stool were often feared by other members of court; they held highly confidential knowledge about political and personal affairs and, importantly, the king’s ear. Sir Anthony Denny, groom to Henry VIII*, was even given the responsibility of Henry VIII’s stamp, which acted as his signature for documents. Lucy Worsley wrote in If Walls Could Talk that the Groom of the Stool got a special golden key attached to a blue ribbon to handle, of which no other copies could be made, just for the king’s personal rooms. Personal attendants in general were proud about their status symbols as such, she added, and often bragged about it—but to be the king’s groom was most coveted of all.

In the early 17th century, Sir Thomas Erskine was King James I’s captain of the yeoman of the guard, and eagerly combined this job with being Groom of the Stool, which, as Keith Brown wrote in his book on noble power in Scotland, gave him “crucial influence over the king.” Grooms were sometimes embroiled in other areas of political power, too—Henry VIII’s groom Sir Henry Norris was politically involved with the queen, Anne Boleyn, and was executed along with her after she fell from her husband’s favor. According to Worsley, both James I and his successor King Charles I were so swayed by their grooms’ counsel that in some respects, political discussions of the king’s privy helped fuel the 17th-century English Civil War.

In Sovereign Ladies, Maureen Waller noted that queens tended not to employ this royal particular service, though they could marry into a powerful position through a Groom of the Stool. A woman named Katherine Ashley held the position for Queen Elizabeth I in the 1500s, though she was actually Chief Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber, and attended to the queen in her private day room, helping her bathe and wash her hair. In modern times and as of 2006, the queen often has her own private bathroom, Waller added.

During the mid 1700s, using a Groom of the Stool at the close stool itself began to fell out of favor. Sir Michael Stanhope for Edward VI was the last to perform the full job; the last Groom of the Stool was technically James Hamilton for the Prince of Wales in the 1800s, though by then the position had shifted to dressing duties, and was renamed “Groom of the Stole” referring to the latin word for clothing, stola. Victorians, it seems, were a little more interested in true privacy.

*Correction: This story initially referred incorrectly to Henry III—it has been updated to the rightful Henry VIII.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook