Our Breath and Sweat Almost Ruined King Tut’s Tomb

But a new circulation system is making things better.

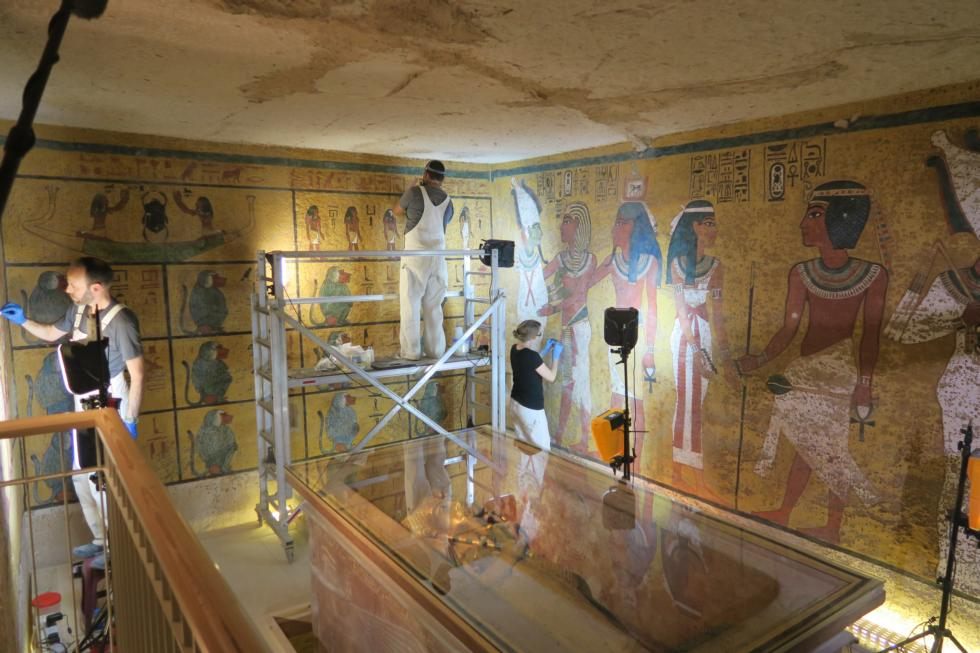

When British archaeologist Howard Carter cracked into Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, he was dazzled by the contents—“Gem-Studded Relics in Egyptian Tomb Amaze Explorers,” The New York Times declared—but he wasn’t especially impressed by its walls. The resting place of the young ruler is humble compared to others in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings—four rooms occupying 9,762 cubic feet, less than a quarter of the size of the burial site of Ramesses V and VI. Conservators have remarked that the paintings on the thin clay plaster covering the rough-cut walls of the burial chamber show numerous drips and other signs of haste; the tomb was likely prepared quickly, since the ruler died young. Carter once characterized the scenes depicting Tut’s funeral procession and the journey of his successor, Ay, as “rough, conventional, and severely simple.”

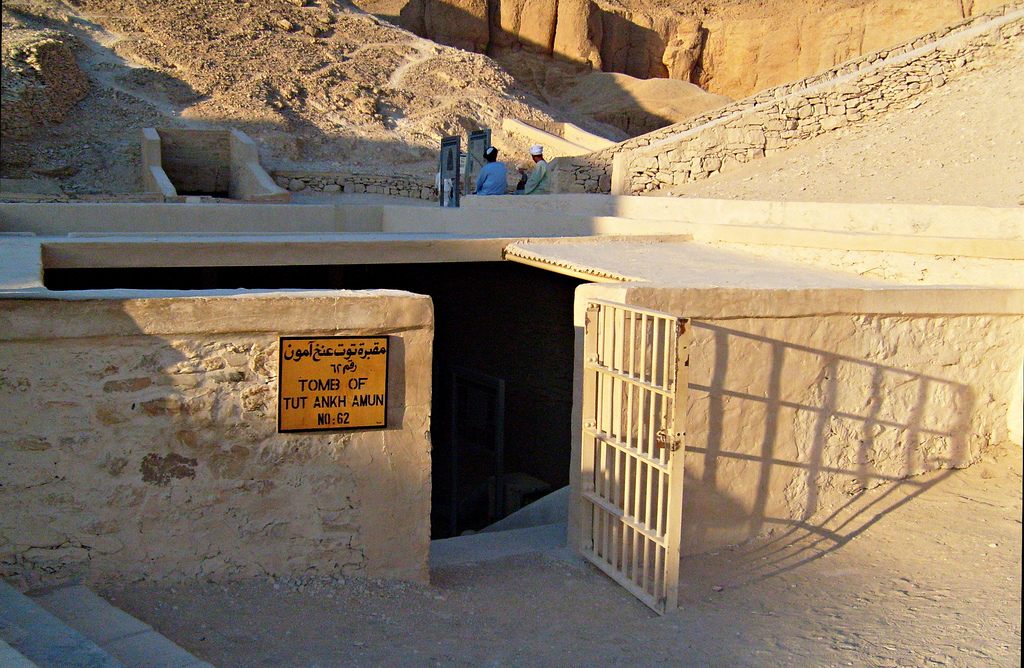

Tourists haven’t seemed to mind the rush job on the walls—in fact, they have been utterly entranced. Just before the 2011 Egyptian revolution, several hundred people per day squeezed into the confined spaces. Each and every one of those visitors had inconvenient but unavoidable habits: namely, breathing and sweating. In those cramped subterranean quarters, moisture is the enemy.

Visitors can mean all sorts of trouble for historic sites. Footsteps can quake fragile, old structures, and people have a tendency to leave behind scribbled musings and wads of gum. Even the lightest-trodding, most respectful visitor presents passive problems. In Tut’s tomb, “visitors increase relative humidity, elevate carbon dioxide levels, and along with natural ventilation into the tomb, promote the entry of fine airborne particles,” wrote researchers, led by the Getty Conservation Institute’s Lori Wong, a wall paintings expert, in a 2018 paper in Studies in Conservation.

In partnership with Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities, Getty conservators just wrapped a nearly decade-long conservation project to guard the tomb against the impact of heavy-breathing, heavy-sweating visitors. (The tomb remained open to the sweaty masses nearly the whole time.) Before they began, the team had to quantify just how bad the problem was. The researchers installed a suite of monitors to track air temperature, relative humidity, carbon dioxide concentration, and other environmental factors. In 2009—the first year of data collection—relative humidity inside peaked at 70 percent in September, one of the desert’s most sweltering months. (Meanwhile, humidity averaged less than half of that just outside the tomb.) The mean temperature indoors hovered around 80 degrees Fahrenheit all year long; National Geographic once described the environment inside as “almost tropical.” It was impossible to pin down the precise levels of carbon dioxide because the air in there routinely maxed out the sensor, which went up to 3,500 ppm—roughly ten times higher than the concentration outside, according to conservators.

It wasn’t a pretty picture. Visitors brought in dust that fell like snow on the glass case holding Tut’s sarcophagus. On the wall paintings, the dust made the humidity problem more troublesome, because it could “encourage moisture uptake, damaging paint layers, and can cement itself to the surfaces, making it difficult to remove,” the authors wrote. Fluctuating humidity levels—seasonally or over the course of a day—can cause the plaster beneath the paint to expand and contract, threatening the integrity of the painted scenes. Carbon dioxide wasn’t a concern for the wall paintings, but rather “a serious contributory factor to visitor health and comfort,” says Neville Agnew, a specialist at the Getty Conservation Institute and a project leader. Perspiration and respiration were among the main culprits.

Damp, musty humans have caused problems for painted surfaces around the world. Some 700 years ago, Giotto bedecked the walls of the Scrovegni Chapel, in Padua, Italy, with frescoes. “The frescoes’ chief enemies are the excessive number of visitors, which have averaged 350,000 annually in recent years, and the air from outside,” architect Gianfranco Martinoni, charged with restoring the works, told the International Herald Tribune in 2000. “The moisture emitted by human bodies and breathing combines with airborne dust and other pollutants to produce an acidic chemical reaction that is literally eating into the surface of the paintings.”

To protect them, the conservators installed a series of chambers that guests have to pass through before stepping into the chapel. These spaces filter the air and remove dust before it has a chance to blow around and land on the paintings. Conservators at the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City ran with a similar concept when stiff-necked visitors to Michelangelo’s 500-year-old paintings neared an astonishing six million a year. The crew did everything from lowering temperatures, to laying down debris-grabbing carpets, to installing vents to “suck dust from clothes and bodies” to keep the damage from human moisture to a minimum, the Vatican Museums’ director, Antonio Paolucci, said in 2012. By 2015, the filtration system also helped cut the carbon dioxide by half, Vatican conservator Vittoria Cimino told Reuters.

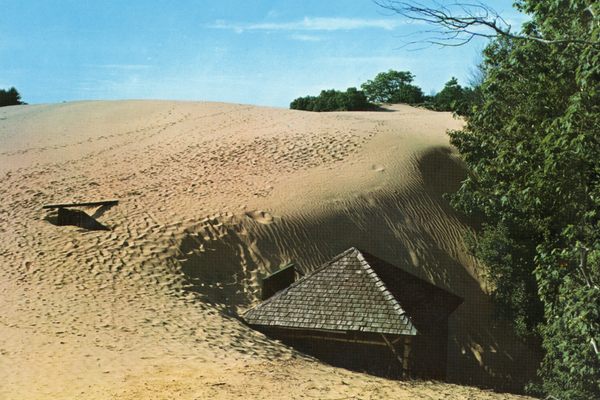

One tactic for protecting Tut’s tomb was to redirect some of the bodies and mouths elsewhere—specifically, to a meticulously fashioned replica of the tomb, a bit more than a mile away. Every nook and cranny was photographed and scanned. “Every bit of micro bacteria is in its place, every crack, every flake of paint,” artist Adam Lowe—whose company Factum Arte spent five years assembling the project—told National Geographic. “It’s effectively like a portrait, or a performance, of the tomb from when we recorded it in 2009.”

At the original tomb, to keep the paintings safe, the researchers set a goal to cap the maximum relative humidity at 60 percent, and to limit the daily fluctuation in relative humidity to no more than 20 percent. (A relative humidity range of 40 to 60 percent is often a target for museums, but “we have a different situation,” in the desert environment, Wong says.) For visitors’ sake, the team aimed to cap carbon dioxide at 1,500 ppm. They were also happy to find that a smattering of potentially worrisome brown splotches turned out to be dead microbes, and weren’t a concern in the humid conditions.

To reach these goals, they installed a ventilation system. The machine “supplies filtered ‘clean’ air at the south end of the visitor platform and then extracts the ‘dirty’ air at the north end, thus enveloping the visitors in the antechamber and limiting spread of the dirty air into the burial chamber,” the authors wrote in the 2018 paper. The team saw promising results shortly after it was installed in 2015. By 2016, they were recording relative humidity of 25 percent in the winter and spring, and 29 percent in the summer/autumn—a massive improvement. Daily humidity swings were also less marked.

But, because of the revolution and safety concerns, visitorship was way down, too—from 14.7 million visitors to Egypt in 2009 to 5.4 million in 2016—and this complicated the picture. Tourism appears to be rebounding, though it’s still below previous levels. The ventilation system is designed to handle a steady stream of visitors, but its current successes are products of “a current environment in which reduced visitation has already decreased the moisture and carbon dioxide in the tomb,” the authors wrote.

So what happens as foot traffic picks up? A new viewing platform keeps visitors farther from the wall paintings, and new floors limit the dust people track in. And, if conservators get their way, fewer people will cram into the space at once. In the 2018 paper, Wong and her team recommend no more than 20 visitors at a time, staying for roughly 10 minutes each. (The recommendation “will be refined as data are accumulated,” Agnew says, and the Ministry of Antiquities staff is tasked with managing visitor numbers and monitoring the condition of the tomb.)

In any case, the Getty team doesn’t anticipate an outcry from visitors. A new sign outside describes the impact guests can have on the tomb, and Agnew says that people are sympathetic to its fragility. “Our experience at other sites indicates that there is acceptance if the reasons for restrictions are made apparent,” Agnew says. Plus, when visitors do get in, they’ll have a good view because the viewing platform “was actually extended further into the burial chamber than previously to provide a better vantage of the wall paintings” while keeping people away from direct contact, Wong says. If you do go, try to play it cool—and maybe let the place take your breath away, at least for a moment or two.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook