America’s Tumultuous Love Affair With Kudzu

Before the plant was considered a scourge, it was used for decoration, as livestock fodder, and to fight erosion.

In February of 1937, a newspaper columnist in Asheville, North Carolina, announced the start of a poetry contest. The prompt? He wanted odes to kudzu, the broad-leafed vine that, people would later say, grows so fast it is best fertilized with motor oil. As the columnist wrote, it was a great muse: the vine was “good for nearly everything but influenza or frostbite.” It was also not a hard ask poetically: “Who is so poor a poet that he can’t find a rhyme for kudzu?”

Over the next few weeks, responses came creeping in. The winner, who called herself “The Countess of Kudzu,” managed three different rhymes, based on varying pronunciations of the plant:

“In our section of the woods you

Save your soil and soul with kudzu

No one suffers from the floods who

Gives a little time to kudzu

Nor gash nor gully ere denudes who

Covers up his land with kudzu.”

If you’re up on your contemporary botanicals, you may recognize kudzu as a well-known scourge, prone to indiscriminately overgrowing everything from forests to fields to abandoned buildings. For decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, though, the plant was not a vegetative villain, but a horticultural hero. Used as everything from a decoration to a feed crop to an erosion-fighter, it was lauded for its fast growth and near-indestructibility—the same qualities that now have people building barriers around it, injecting its roots with helium, and even lighting it on fire to get rid of it.

Kudzu debuted in the U.S. in 1876, as part of the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, which also introduced the country to such all-American classics as the telephone, the time capsule, and the Statue of Liberty’s torch. A sort of plant diplomat, it was brought over from Japan—where it had long been used as livestock feed, as well as to make paper—and installed in the Expo’s Japanese Garden.

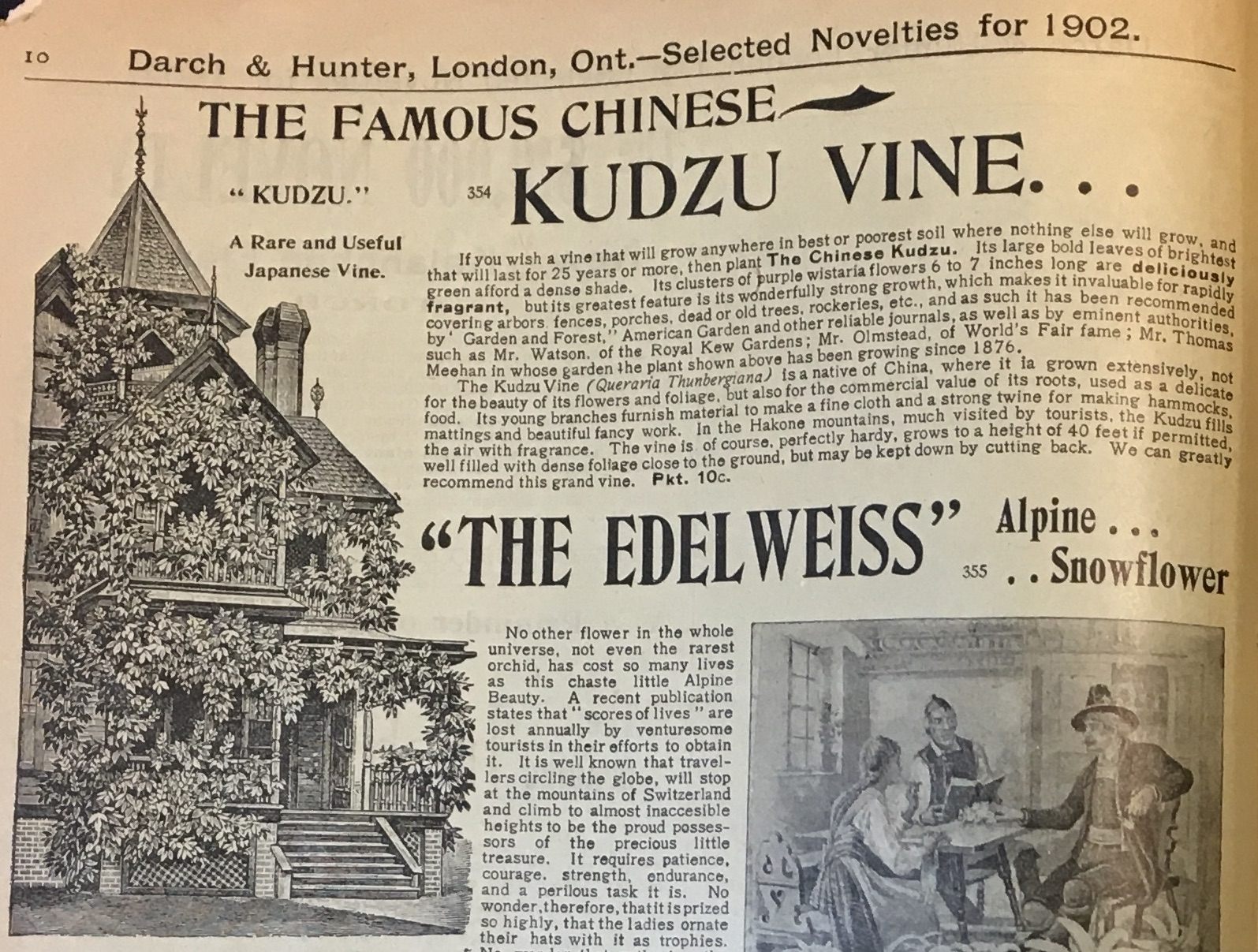

There, it wowed visitors with its dense foliage and purple blooms: traits that, combined with its tendency to spread rapidly, made it ideal for gardeners hoping to inject some quick and easy green into their environs. Nurseries began carrying seeds and young plants, granting them rave reviews in their catalogs. “This is the most remarkable hardy climbing vine of the age,” read one kudzu ad from 1909. “For rapidly covering arbors, fences, dead or old trees, porches or rockeries there is nothing to equal it.” Before long, people began calling it the “front porch vine,” and happily covering their homes with kudzu toupees.

Two of these people were Charles and Lillie Pleas, a couple of farmers living in Chipley, Florida. The Pleases bought some kudzu seeds in 1903, and planted them around their brush pile in an attempt to hide the brush from view. As Charles describes in a 1909 article for the Ocala Evening Star, the kudzu soon outgrew its patch, creating a two-and-a-half-foot-deep tangle of vines and leaves near their house, and creeping into the driveway, the neighbor’s yard, and the stables.

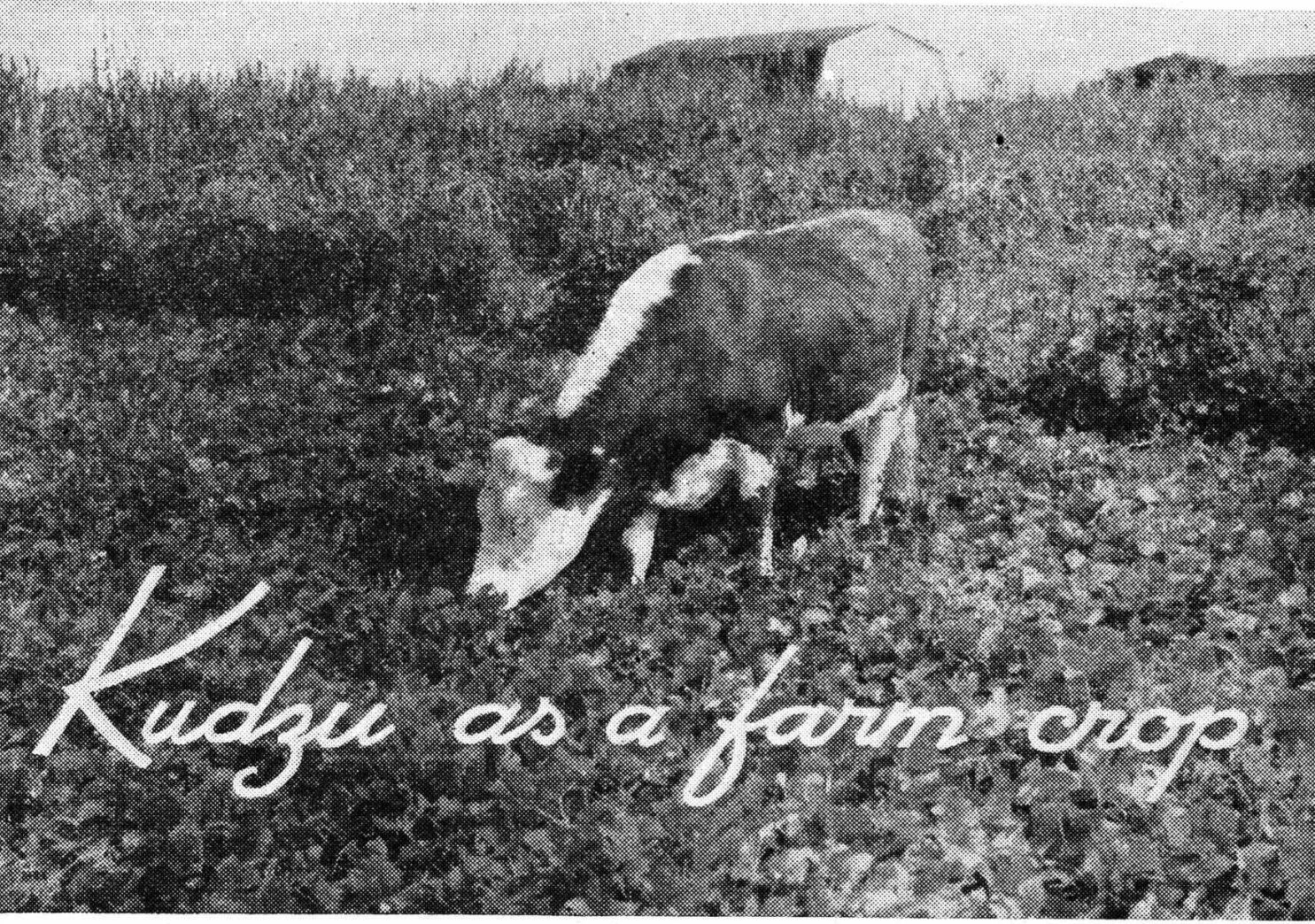

Seeing how much his horse liked nibbling on it, Charles decided to cure some kudzu into hay—it smelled sweet, he wrote, and remained bright green—and test it for nutritional value. Seeing that it was comparable to other popular feeds, the Pleases soon began selling kudzu seedlings as a forage crop, pitching it as something that would fill a seasonal need. “The forage plant that will tide the farmer and stock raiser over the long, hot, dry summer … will fill a long felt want,” Charles wrote. “Kudzu will do it.”

Word of this new forage plant spread, and plenty of Southern farmers used it: newspaper archives show rave reviews from North Carolina (“cows and horses are greedy for it”) to Louisiana (“its growth seems simply magical”). But things didn’t really take off until 1935, when the U.S. Government got in on the action.

That year marked the creation of the Soil Conservation Service (SCS), a USDA sub-agency dedicated to fighting erosion. As Mart Allen Stewart explains in an article for the Georgia History Quarterly, the South at the time was suffering from land integrity problems, losing precious topsoil to everything from railroad construction to cotton monoculture. Kudzu, the SCS thought, could hold the very land together, shielding it from further breakdown, and even rebuilding the land by trapping sediment in its tendrils. Plus, it was a nitrogen fixer, and could help to rehabilitate nutrient-starved fields. “What, short of a miracle, can you call this plant?” the head of the SCS, Hugh Hammond Bennett, asked in Reader’s Digest in 1945.

The SCS set up kudzu nurseries, taking clues from the Peases and others who had grown the crop for forage. Seedlings “were shipped throughout the Southeast and distributed to farmers, who applied the vine to rilled and gullied croplands, and to railroads and highway departments that planted the seedlings along exposed rights-of-way,” writes Stewart. The SCS also provided economic incentives to farmers, paying them up to $8 an acre to plant the vine, the equivalent of about $140 today. It worked: “Between 1935 and 1946, more than half a million acres in the South were planted in kudzu,” Stewart tabulates.

Meanwhile, a cultural kudzu renaissance also picked up steam, led largely by a Georgia farmer named Channing Cope. As Derek Alderman details in Geographical Review, after Cope revitalized his own land with the plant in the late 1920s, he became a kind of kudzu evangelist, with “an almost religious confidence in [its] ability to rebuild the southern landscape.” Cope created a kudzu-focused media empire, singing the plant’s praises in his newspaper column (“Kudzu is the Lord’s indulgent gift to Georgians”), on his daily radio show, and in a book called Front Porch Farmer (“we would be idiotic to refuse its help”).

In the early 1940s, Cope started the Kudzu Club of America, which held annual pageants and kudzu-planting contests, and eventually reached 20,000 members. Even as the rest of the country soured on the plant, he refused to turn on it, which may have led to his own demise: according to one friend, the heart attack that killed Cope in 1961 occurred when he was trying to run off some teenagers who were hanging out in a patch of kudzu on his property.

Throughout, there had been some hints that all of this was too good to be true. In a 1914 issue of The Garden Magazine, columnist Nina R. Allen reports that, seduced by catalog images of climbing vines with “innumerable clusters” of flowers, she bought a few in hopes of covering an ugly fence. After planting them, they indeed covered the fence, as well as much of the backyard. “It has never produced a blossom,” she wrote, “though every spring from twenty to thirty sprouts have shot up from the root, sprawling shiftlessly in every direction and waiting for somebody to come and do something.” She ended up moving away, leaving the weedy interlopers for the next occupant.

Some farmers were skeptical, too. “I have been asked by many if it can be got rid of, and if it doesn’t become a pest,” Pleas wrote in 1909. He offered a bit of a non-answer: “Plant it where it can stay, and you will never want to get rid of it.” In 1915, other states were singing its praises as a forage crop, the Honolulu Advertiser pointed out that “as far as Hawaii is concerned … the Kudzu vine is here considered simply as a very troublesome weed.”

Eventually, the rest of the country came to this conclusion as well. Beginning in the 1950s, Stewart writes, kudzu was causing a number of infrastructural problems: climbing telephone poles, overgrowing native trees, and shorting out power lines, and massing on railroad tracks and causing trains to skid. In 1953, kudzu was removed from the list of USDA-recommended cover plants. In 1970, it was officially labeled a weed plant, and by 1997, it had been promoted to “Noxious Weed.” In many states, it retains that title to this day, accompanying such infamous species as poison hemlock and the giant hogweed.

Eighty years after that Asheville poetry contest, any verse about kudzu is by necessity more complicated. Some characterizations remain straight-up villainous: one contemporary song describes its tendrils as “green, mindless, unkillable ghosts,” and articles and books call it “the vine who ate the South.”

But even as recent decades have seen prolonged efforts to beat back the plant’s spread, kudzu has experienced a bit of a metaphorical resurgence—many authors and artist consider it a rich symbol of complexity and resilience, using it to stand in for everything from forbidden desire to the region’s complex relationship with its own past. No matter how hard we may try to uproot it, kudzu is entwined with American culture, hanging on through the ups and downs. What could be more poetic than that?

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook