In This Beautiful Library, Bats Guard the Books

The winged residents have been lurking in the stacks since the 18th century.

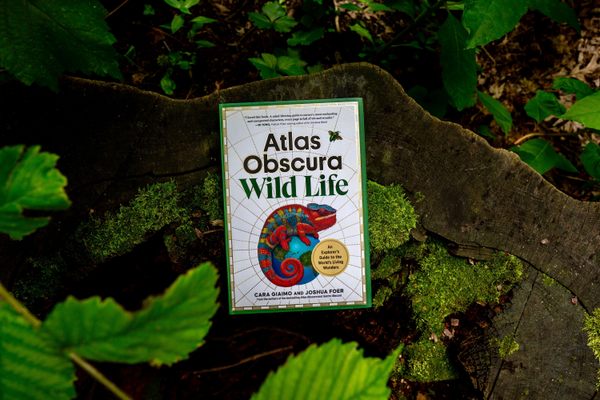

Each week, Atlas Obscura is providing a new short excerpt from our upcoming book, Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders (September 17, 2024).

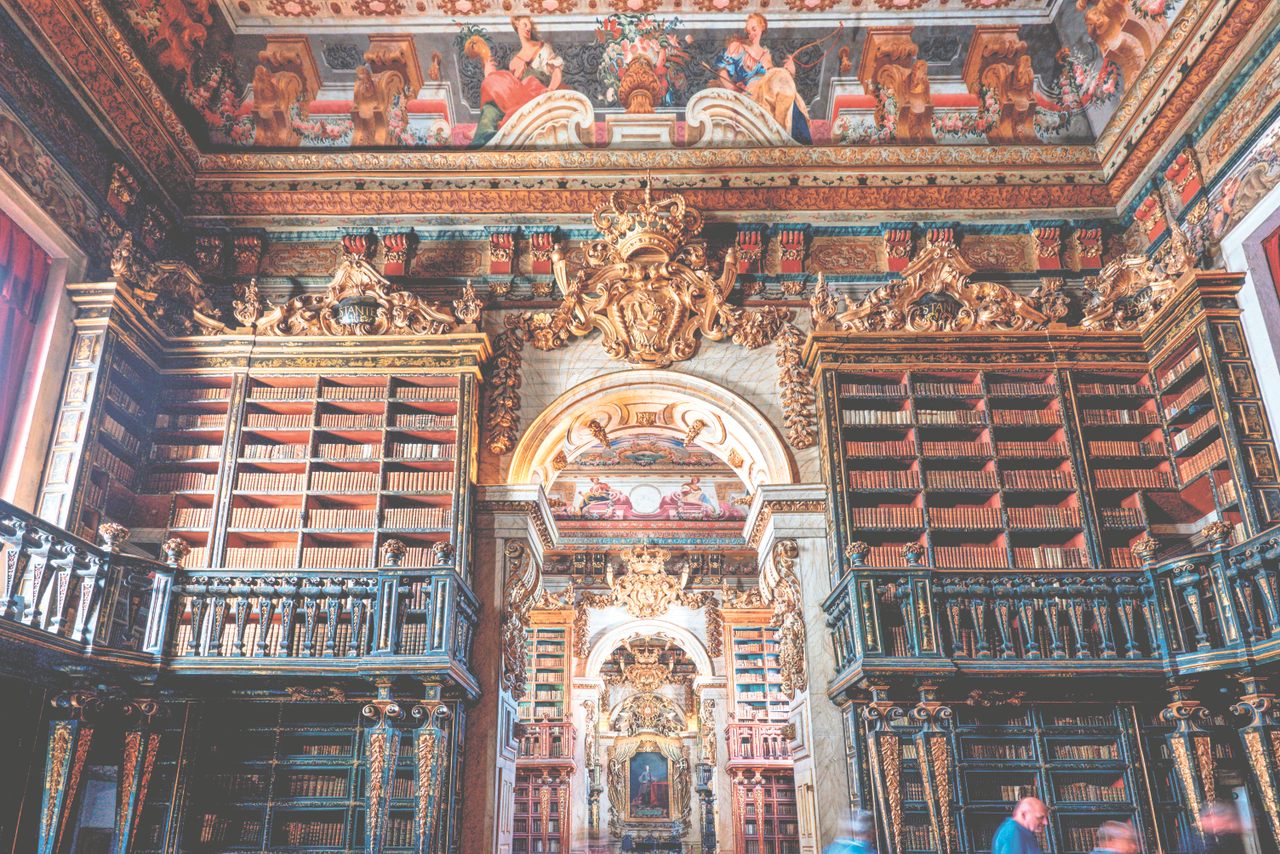

The 60,000 books in the Joanine Library are all hundreds of years old. Keeping texts readable for that long, safe from mold and moisture and nibbling bugs, requires dedication. The library’s original architects designed 6-foot (1.8 meters) stone walls to keep out the elements. Employees dust all day, every day.

And then there are the bats. For centuries, small colonies of these helpful creatures have lent their considerable pest control expertise to the library. In the daytime—as scholars lean over historic works and visitors admire the architecture—the bats roost quietly behind the two-story bookshelves. At night, they swoop around the darkened building, eating the beetles and moths that would otherwise do a number on all that old paper and binding glue.

The library dates the bats’ entry to the late 18th century. That’s when records indicate the purchase of large leather sheets from Russia, presumably to protect the hall’s desks and tables from the nightly rain of guano. Employees use the same system today, while the books themselves are behind wire mesh, says the library’s deputy director, António Eugénio Maia do Amaral. (The bats’ tendency to pee next to a portrait of the library’s namesake, King John V, is harder to address.)

Although visitors tend to be very curious about the bats, library employees mostly leave them in peace to do their jobs. As such, less is known about them than you might expect, given that they live in a knowledge repository. Two types have been identified: European free-tailed bats and soprano pipistrelles, both small and nimble species. Although no one sees them hunt, it’s easy to imagine them free diving from the painted ceilings and slaloming between the gilded balusters.

Their skill and discretion—rarely do you have to hush a bat—make them valuable members of the community. Maia do Amaral calls them “honorary librarians.” When the Joanine’s enormous wooden doors were replaced in 2015, carpenters preserved the gaps the bats use when they leave each night to drink from the river. Some speculate that previous caretakers introduced them to the building on purpose.

But those who work with them now think it’s more likely the bats, who value peaceful homes, found their way in on their own. After all, says Maia do Amaral, “What can you think of quieter than a library by night?”

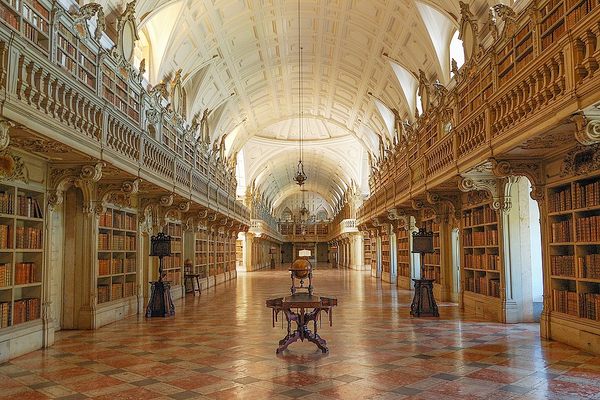

Range: Joanine Library at the University of Coimbra in Coimbra, Portugal

Species: European free-tailed bat (Tadarida teniotis) and soprano pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pygmaeus)

How to see them: The Joanine Library offers regular guided tours, during which you may hear a bat squeak. If you want to see one in action, your best bet is to attend one of the library’s evening concerts, which occur right at the start of their dinnertime. Try to feign interest in the books, out of politeness.

Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders celebrates hundreds of surprising animals, plants, fungi, microbes, and more, as well as the people around the world who have dedicated their lives to understanding them. Pre-order your copy today!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook