Saving the Sounds of the Early 20th Century

Some recordings in the New York Public Library’s wax cylinder collection haven’t been heard in generations—until now.

It’s 1903 in New York City. Freezing winter winds funnel through the city as women in elaborate evening gowns and long white gloves and men in long dark tailcoats make their way to the Metropolitan Opera house on 39th Street. Tonight, for only the third time, the Met’s production of Tosca will be taking the stage. But the audience filing into the elaborate theater has no idea that suspended above them in the rafters is the Met’s librarian, Lionel Mapleson, and his state-of-the-art wax cylinder phonograph. From audience reactions to soprano Milka Ternina’s high notes, Mapleson captured it all. After catching the “recording bug,” as he wrote in his diary in 1900, Mapleson went on to record more than 130 wax cylinders of live opera performances, creating the only recordings of some of opera’s most legendary singers.

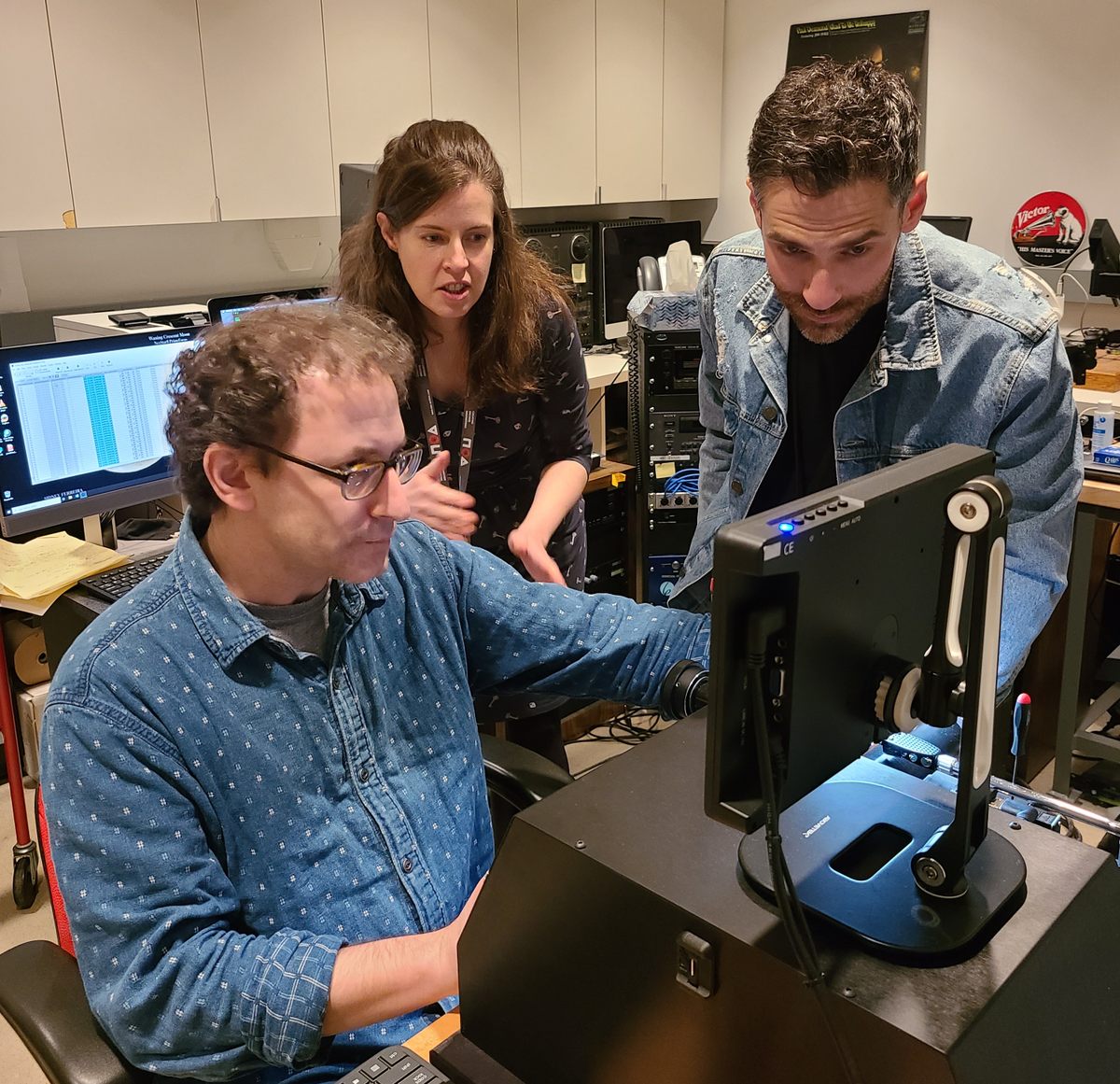

The Mapleson cylinders are the prized possession of the New York Public Library’s vast wax cylinder collection, which comprises about 2,700 recordings. Only a small portion of those cylinders, around 175, have ever been digitized. The vast majority of the cylinders have never even been played in the generations since the library acquired them. But that’s all about to change. The library recently acquired a nearly $50,000 machine to create digital recordings of their wax cylinder collection. In the world of wax cylinders, innovations like this come about only once every 20 years, says Jessica Wood, the library’s assistant curator of music and recorded sound. “To be able to hear stuff that was recorded in the 1890s is pretty magical,” she says.

Sound restoration engineer Nicholas Bergh spent two decades designing the revolutionary new machine, known as the Endpoint Audio Labs cylinder playback machine. To date, seven exist around the world, including one purchased by a private collector who has made his vast collection publicly available online (sign up required). Bergh’s machine, which looks a bit like an old-school phonograph attached to a high-tech computer, uses a laser to read the grooves on a wax cylinder. On an actual phonograph a needle would do that work, tracing the grooves carved onto a wax-coated cardboard cylinder, which creates a sound that can be amplified. (Imagine a cylindrical record that rotates rather than spinning on a turntable.) When asked if he feels any kinship with phonograph inventor Thomas Edison when making his own modern machines, Bergh says with a laugh, “yeah, I guess so.”

In the late 19th-century, a battle between some of the century’s finest minds was unfolding over who would be the first to patent and commercialize recorded sound equipment. The key players were Edison and Alexander Graham Bell. In 1877 Edison was the first to invent a machine to capture and playback recorded sound: the tinfoil phonograph, which recorded sound using a needle that imprinted grooves into a piece of tinfoil. When Edison first showed the machine publicly, “the story goes that someone fainted, you know, hearing their voice back for the first time because no one had ever heard that before,” says Bergh. “It was quite shocking apparently.”

But Bell wasn’t far behind Edison. Within the next decade, Bell improved upon Edison’s design, swapping out tinfoil with studier wax cylinders—an improvement that Edison would also soon adopt. Soon wax cylinders abounded. Edison set up coin-operated phonograph machines that would play pre-recorded wax cylinders in train stations, hotel lobbies, and other public places throughout the United States. By the end of the century, it seemed that Edison had won the battle over recorded sound. That is until German-American inventor Emile Berliner developed the far more popular flat disc record and gramophone. Edison had primarily designed his machine as a recording device, and it turned out people were far more interested in listening to music than their own voices.

In his office, Bergh has replicas of almost every type of early sound recording machine—from Edison’s first tinfoil phonograph to Bell’s later phonograph-graphophone (an admittedly unwieldy name), which played wax cylinders. “The main reason why I have all this old stuff is, at least in my experience, it kind of takes fully understanding how the recordings are made to properly extract the best sound quality from them,” says Bergh. While developing his Endpoint machine, Bergh would use his replicas to make experimental recordings to help understand the flaws of the original machines. Only then could he work out ways to correct them, like using a laser to smooth out the ever-present “wow-y sound,” as Bergh puts it, of the original recordings caused by the rotation of the cylinder. In addition to capturing the original sound of these wax cylinders, Bergh’s machine clarifies that sound, removing the imperfections often found in wax cylinder recordings.

Today Bergh’s innovations are bringing to life the sounds of the early 20th-century. The New York Public Library has already digitized some cylinders from its collection, including the Mapleson collection. But the process, which utilized the now-outdated Archeophone cylinder phonograph, was a time-intensive one that took days to turn around a finished digitized recording. With Bergh’s Endpoint machine, library audio engineers will be able to digitize five to six cylinders a day.

For many of the cylinders in the collection, librarians like Jessica Wood only know what’s been preserved on them based on notes written on the cylinders’ sleeves and boxes. Wood knows there’s a collection of about eight cylinders from Portugal, which may be some of the oldest recordings ever made in the country. There are also five Argentinian cylinders that have preserved the sound of century-old tango music. A couple of cylinders contain the music of the police band of Mexico City “that I’ve heard are probably beautiful based on historical sources from the time,” says Wood.

But hundreds of the library’s cylinders don’t have any notes whatsoever about what may be recorded on them. Some might be family home recordings of a birthday or holiday. Others might contain unreleased musical recordings or vaudeville comedy routines. No one knows. “I’ve just been staring at the containers and imagining what they might contain based on the labels,” says Wood.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook