Confessions of a Poet-for-Hire

Brian Sonia-Wallace is about to become the first-ever Writer-in-Residence at the Mall of America. And this isn’t the first time he’s snagged a corporate sponsorship.

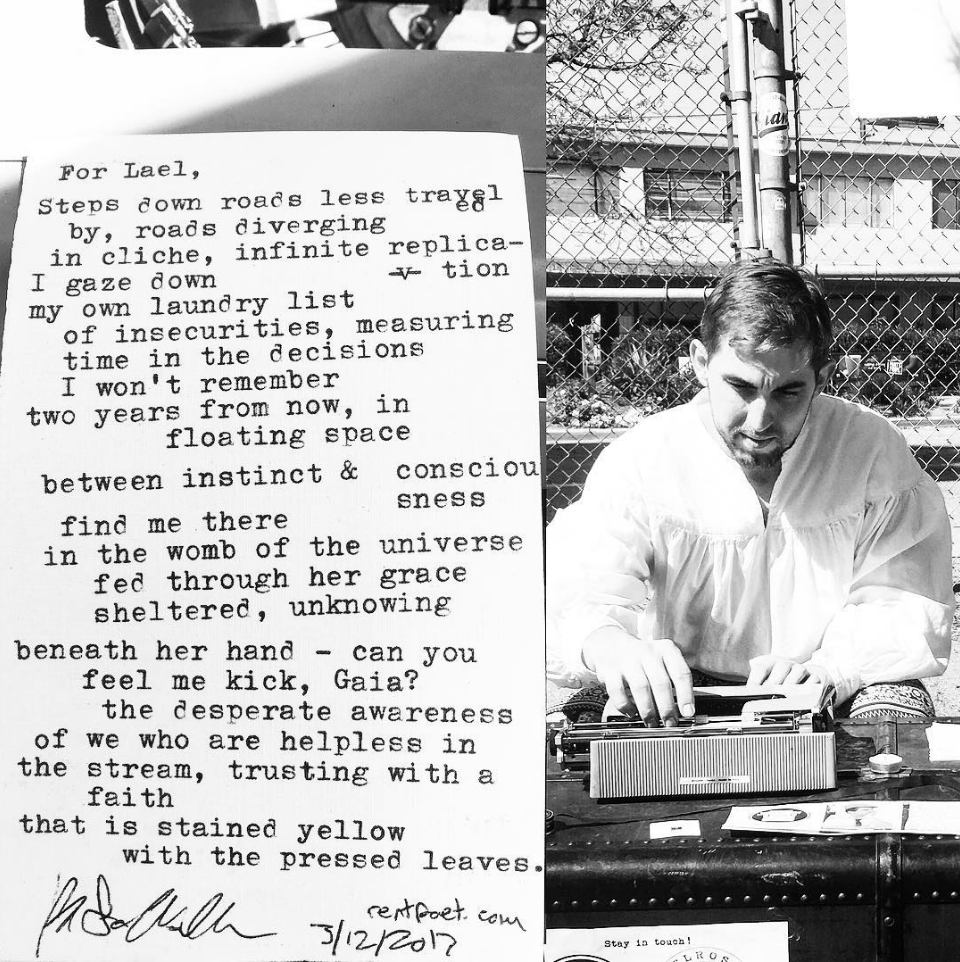

When the poet Brian Sonia-Wallace answers the phone from his apartment in Los Angeles one recent afternoon, there’s clearly a skip in his step. “I ordered a typewriter from 1917, and it just arrived,” he says. “It’s not fantastic, but it was $100, and I’m pretty chuffed with it.”

Despite his penchant for old technology, Sonia-Wallace’s literary career has been decidedly contemporary, even futuristic. Rather than shutting himself up in an office and seeking wide publication in literary magazines, he lugs his typewriter out to the street, where he writes poems individually tailored to passers-by. And instead of chasing university jobs, he aligns himself with corporations and other large entities, having served as a poet-for-hire for Dollar Shave Club, Google, and the U.S. National Parks Service.

Earlier this month, Sonia-Wallace was announced as the first-ever Writer-in-Residence for the Mall of America. It’s just one of the (paid) adventures he has planned for June—others include a stint writing screenplay fragments on the street for L.A. Tourism, some time in the Poetry Tent at Michigan’s Electric Forest music festival, and that other golden corporate writing assignment, an Amtrak residency.

We spoke with Sonia-Wallace about his strategies for keeping poetry alive in a time and place that doesn’t seem too keen on supporting it, and how he keeps snagging all these paid poetry gigs.

When did you first know you wanted to be a poet?

I’ve been writing all my life, since I was a kid. I went to university in Scotland. I’m from L.A. originally, and I kind of wanted the opposite, so I went to college in a small medieval Scottish fishing village, which I think is about as far from L.A. as you can get. And I would go on walks through the farmland of Fife, and wear a flat cap, and call myself a poet, and write poetry and read it to whoever I was with. That was, I guess, the start. In some ways, it’s kind of a character—it’s a little bit of a game. There’s something really gleeful in being able to tell someone some words you thought of one time, and have them have an emotional response and be invested, and be engaged—and be like, “Me too!”

When did you take the leap and make poetry your full-time occupation?

I came back to L.A. after college. I did a lot of artistic internships, and wound up doing a nonprofit grant-writing job, which I think gave me a lot of skills in terms of being able to do a budget, being able to pitch a project—how to do planning and reporting when, at the end of the day, you’re working with other people’s money. So that was a huge and unforeseen [step in that direction]—something that wasn’t what I’m doing now, but definitely led to it.

Through that, I kind of went: “I’m raising money for other people to make their thing. Could I raise money for myself to make my thing?” And so in 2014, I left my job and I started doing art independently. The poetry wasn’t actually the first thing that I landed on—that came a number of months in. I’d been doing a lot of different poetry actions. I do writing workshops in a park with a bunch of friends on typewriters, and we’d post the poems around the neighborhood. The idea was to create guerrilla art galleries, putting poetry in people’s everyday lives in public spaces. I’d been playing with that. But then in September 2014, I ended up having a commission for a theater piece that got cancelled. So I was like, well I can either get a minimum wage retail job, or I can try writing poems on the street.

What was life like as a roaming poet-for-hire?

I was just trying out writing everywhere. Showing up to farmer’s markets, showing up to art gallery openings, going to taco truck festivals. Just like, “Where are there people who maybe are interested in spending a little bit of money and having an experience?”

I write poems based on customer requests. I remember in that first month, writing a poem for a 6-year-old in a parking lot at night. [The words of his request] are in other subsequent poems, which I think is why they stick in my mind. He said, “I want a poem about ‘I love you Grandpa,’ because he just passed.” So there was this incredibly adorable 6-year-old, and then also, his mom was right there with him, so her dad had just passed away. Writing something at his level that would also affect her, and that would be a tribute to someone who I had never met—it was a really interesting challenge.

A surprising number of people want poems about their dogs. I guess that’s a thing that people need poems about. A lot of people just get whatever’s important to them, which is kind of an interesting exercise—just going around in public and asking people, “What’s important to you?”

How did this more recent phase of your career get started?

I’d done the poems-on-the-street thing a couple times before, and I had a sense of what I would make in tips. I ended up making California minimum wage before taxes. That was my benchmark. And then that ended up parlaying, in a really organic way, to people I’d met on the street going, “Oh, my company is having this party! Let me see if I can get some money for you to come write for us here.” Or, “I’m having cocktail hour with the city planners, let me see if I can bring you in as a special treat for the guests.”

I think about what I do as poetry as a service, or literature as a service. And I’ve done events where I’ll be next to the bartender, or next to whatever other kind of entertainment is there. There’s something that I love about taking something that we think of as so inaccessible—“Who understands poetry anyways?”—and being like, no, this is something you might want, three drinks in, before going on with your night. It tickles me to mess with that perception a little bit.

I’ve done a bit of work with people who have found me online. My personal site miraculously ended up having really good Google Analytics. It’s on the first page of results if you Google “hire a poet.” There was one old guy who called me, and he was like, “I need a poem for my friend’s wedding in three hours. Can you do that?” And I was like “Whoa, you actually caught me on a good afternoon. Tell me about your friend.”

When did you first start working directly with companies?

There were two [residencies] at the beginning. One of them was from a woman on the street who said “Oh, you know what, I actually do marketing for Dollar Shave Club, and we’ve been talking about having a weekly haiku column. Do you write haikus?” I was like, “Yes, of course I write haikus.” So I worked with them for a few months as the resident poet—not going into their offices, but writing a haiku column for them. It was the lifestyle section—stuff that people who buy the razors might also be interested in. They were interested in doing new releases in film and music, so I would write micro-teasers: Here are all the cultural things that are happening that you might be interested in, but you’re probably busy, so here’s five haikus about them, and you can decide which of them you want to look into more. It was great. It was an interesting mix of having to do research and cultural journalism, but within constraints.

Around the same time, the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, which is just north of L.A., was having an artist-in-residence program. It specifically was targeting kids, and the woman who runs it has a background in youth education work, and is really interested in, “How can we have artists engage youth with the mountains?” So I worked with them, I worked with an after-school program, and we brought late elementary school kids up to the mountains. They all wrote their own plays and short works and performed them based on that experience.

The funny thing about residencies—there’s this [misguided] idea of what a residency actually means. A lot of times it’s just what they’ll call artistic projects, or the idea that it’s an ongoing piece of work. So Amtrak and Mall of America will be the first two really where it’s been residential, where I’ll actually stay in a place that’s being provided.

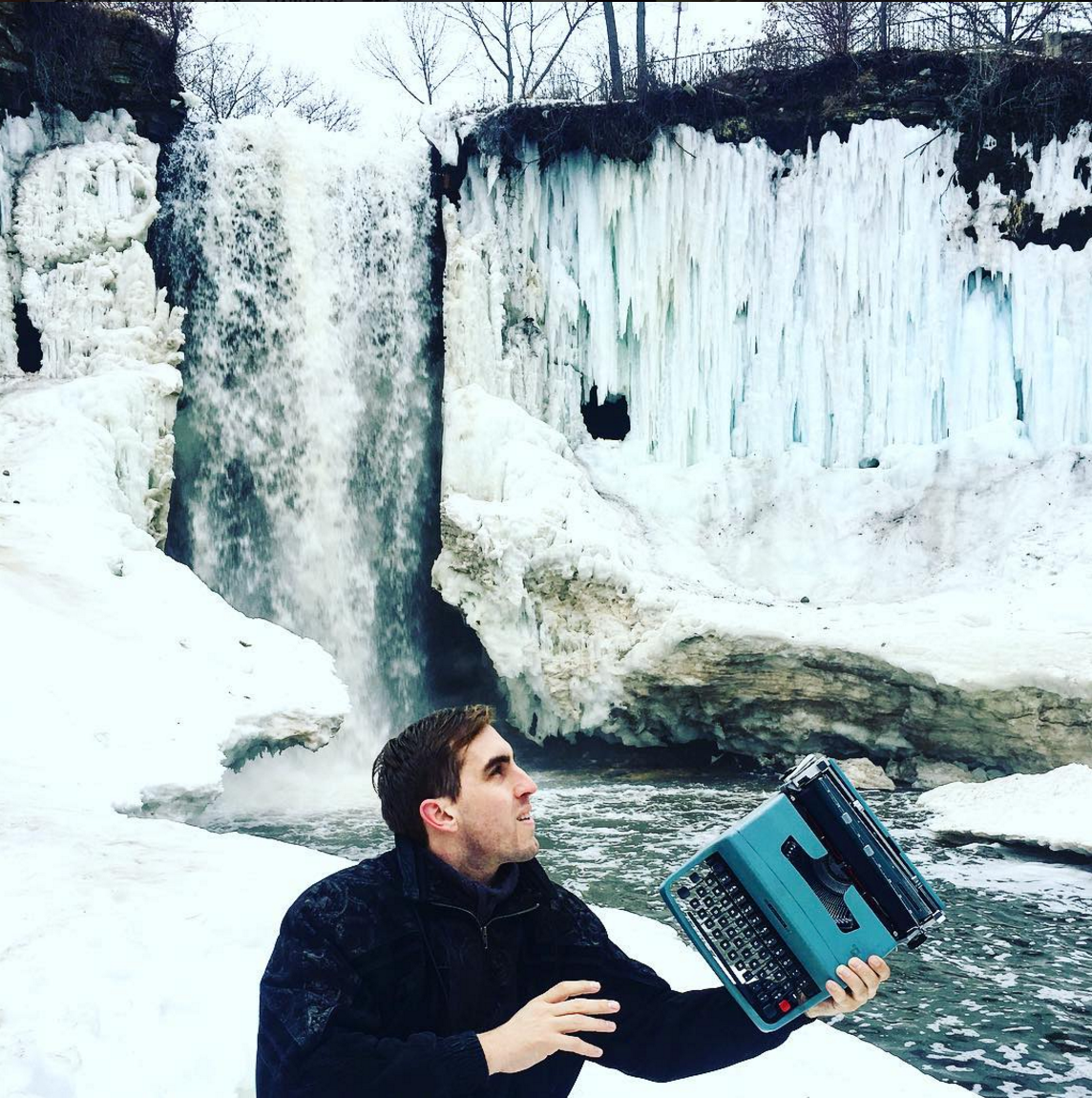

What interests you about these opportunities to embed somewhere specific and write?

My background is in a lot of devised and site-specific theater. And so when I think about a lot of the work that I do now, it’s really in the vein of site-specific poetry. It’s something we don’t do, it’s not a thing—but maybe it should be! Maybe there are interesting ways of, through the connection with place, revitalizing this art form. On Instagram, one of the hashtags to get you into the poetry world is literally #poetryisnotdead. And it’s both sweet and super depressing. I’m like, ‘Whoever said poetry died?” [Puts on “sad poet” voice]: “I can’t get paid, it’s not a thing, I’ll just teach English”—I mean cool, but also, does it have to be that way? There are more improbable worlds.

With site-specific poetry, you can take this tradition that, if you want—and I totally use this in all of these residency applications—you can stretch it back to the Dharma Bums riding the trains in the time of Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. You can stretch it back to medieval bards wandering town to town, singing and writing songs about the town. And maybe some friendly nobility will give you money, and then you’ll praise them for a while, and then you’ll keep moving on. I see a really nice lineage there with what I’m trying to do as an artist working on making money from poetry.

What’s your game plan for the Mall of America? What are you excited about?

I’ve been talking to them a little bit about my environment. It’s really nice as an independent artist who so often scrounges, not necessarily just with resources, but with collaborator time. It’s hard to collaborate with a group of artists who all have six jobs. It’s great to have a designated team where it’s like, this is what they do. They’re the staff at the Mall of America. They’re like, “Oh yeah, what do you want for a backdrop? Let me make you some Pinterest boards?” Cool, you’re going to make a thing for me, and I just have to tell you what I want? Yeah!

So we’ll see what we end up going with. I’ll have some sort of writerly backdrop. I’m interested in creating a little literary-retreat-oasis space, where it’s me on the typewriter, but there’s also some chairs and tables around where people can sit and watch me write. Having some books on them, maybe a take-one-leave-one library. We’ll see how it evolves, but the idea is that it’s more than just a writer sitting and writing. I’ve had some really interesting experiences doing corporate events, where people want to hang out. They don’t want to just get a poem and go on with their day. They want to share their writing, or talk about their favorite book. So we’ll be curating that a little bit.

I am contractually obligated—and I love saying contractually obligated in this context—to be at that desk writing for four hours a day. My goal is to write 20 to 25 poems a day. One of the things I talked to the Mall about, is I said, “Hey, we’re not spending money on travel [because of the Amtrak residency]—do you think we could take that money and use it to bring in local artists as well?” We haven’t finalized or released the names yet, but I’m super excited. It’ll be a different artist from a different discipline for the last two hours every day. I’ll have been writing for a couple hours before that, so I’ll have some work they can respond to. We might do some on-the-spot collaboration.

At this point, you’ve gotten all kinds of coveted corporate poetry gigs—Dollar Shave Club, the National Parks, the city of L.A., various music festivals, Amtrak, and now the Mall of America. What’s your secret?

I think one of the reasons I got this residency was that within my pitch, I made really clear the different generational reactions to what I do. Working on a typewriter, I get nostalgia and I get novelty, along an age line. They’ll either really be taken back, and they’ll want to tell the story of how they learned to type, or how they used the typewriter to type their college essays. Or they’ll be younger people who just think typewriters are super high-tech because they print while you write. I always make a really bad joke—I always say it’s the new MacBook Pro. It’s the worst dad joke, but it works every time.

In general, I don’t have an advanced degree in poetry. I’m not the most literate person in contemporary poetry. I think the key at the end of the day is understanding who you’re writing to. If I’m talking to a corporate client, I understand they have corporate needs. I’m not going to tell them, “Well, I’m writing Moby Dick, and it’s going to be the next great American novel, and you guys need to sit down for 10 years while I do that.” That’s not going to work.

I think we glorify this idea of the creative process as sacred, and the artist as sacrosanct, and that money corrupts, and that pure art should be free from all influences. At the end of the day, I just think that’s bullshit. If you believe that the personal is political, and that art is necessarily political and either progressive or counter-progressive, you have to accept that there’s always going to be a lot of influences pushing on any given work. So it’s kind of interesting to embrace those influences as being very public. I’m not trying to hide them. I’m not going to be like, “I wasn’t in the Mall when I wrote these poems.” I’ve been writing a lot about this lately, which I think is in part as a result of applying to these residencies: How can something that’s commercial still be intimate and personal and true, in a human way?

Why align yourself with corporations at all? What role do you see them playing in the future of poetry?

So many of the residencies I see—even submissions for literary stuff—are really this pay-to-play model. There was one that I was super excited about, where a group of artists go to the Arctic Circle, [but] it’s about $10,000 of cost to the artist. And that’s a fantastic thing for folks who either have a project that will make money that needs them to do that, or people who have that income lying around to do a vacation with some interesting product. I understand why it works in terms of the economics, but the result is just that the cultural producers pay money, and the cultural disseminators make a little money. I don’t think anyone’s getting rich off of the backs of writers—they’re just barely squeaking along by themselves.

At the end of the day you end up with this weird, I want to call it a “trickle-up effect,” where the little money that artists are making, they’re spending trying to get their art out there. There’s not necessarily a career in that. And there’s this hope that you’ll make it, and you won’t have to pay anymore—but I don’t quite understand the pipeline, which is why I’ve kind of avoided it.

I do a lot of arts advocacy work as well, at the city level. I’m a huge proponent of art as a good unto itself, and something that’s worth supporting. When I went to the U.K., Labor was still in power… and the context and the cultural understanding of what art-making means, and who is a patron of the arts, and who art is for, was much broader than it is in L.A., and in the U.S. at large. France has the idea that their biggest export is culture—I would argue that the U.S.’s biggest export is also culture, but we don’t necessarily call it that. And maybe we should think about curating, I guess, a little bit more, and think about the idea that the public has a role in curating the aesthetic and the culture of a place, and that the public’s representative is the government, and therefore the government maybe has a role, too.

I’ve definitely embraced this idea of corporate poetry. I love the idea of showing private companies that poetry can add value to their bottom line, and having them bring poetry in, and enabling poets to maybe not make a full livelihood, but to have a good portion of their career supported by some of these gigs.

So I see what I’m doing as broader than any single residency. If there are a couple of competitions, that’s great. But ideally what I’d love to do is, like, “Hey, Mall of America, holy crap, that was awesome—you got so much media time, you got so much community goodwill. You should do this every year.” That would be ideal for me. And then other people see that, other people start replicating it—if we can build a network of private enterprise supporting the arts and recognizing where artists can come in independently and work with them in a way that’s mutually beneficial, I think that’s about as good as we’re gonna get under a system of late capitalism, and a Republican president and Congress.

Is there anything you’re nervous about going into this Mall of America gig?

The thing I’m worried about, and working on problem solving for, is how to manage the flow of people. Obviously, as many people as possible who want a poem should be able to get a poem. But also I’m one guy, and the Mall is a large place, and this has had a decent amount of publicity. So I’m really interested in the challenge of how to curate who those people I’m writing for are—how to make sure that I’m being fair and accessible, but also that I’m having real interactions, rather than just jotting off three lines as fast as I can.

As far as the writing—one of the really nice things about Amtrak, about Mall of America, about all of this is, I’ve done public writing in so many weird places that I’m not worried about that aspect of it. I did a gala last Friday night where I was outside, and I had to keep a door open to get light because none of the lamps and lights and stuff reached the area that I was. So I was sitting in this open doorway of light. I’ve really worked in many and varied writing conditions. And so I’m not like, “Oh, it’s going to throw me to be next to a Nordstrom.” I think the Nordstrom will be fine.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook