Meet the Giant Salmon With a Weaponized Mustache

Spike-toothed salmon grew nearly nine feet long and sported tusk-like teeth.

A Chinook salmon cuts through the clear, cold waters of the Deschutes River of Central Oregon, his iridescent red scales glinting in the sunlight. And he’s not alone. He is just one of thousands of salmon returning to the spawning grounds where they were born.

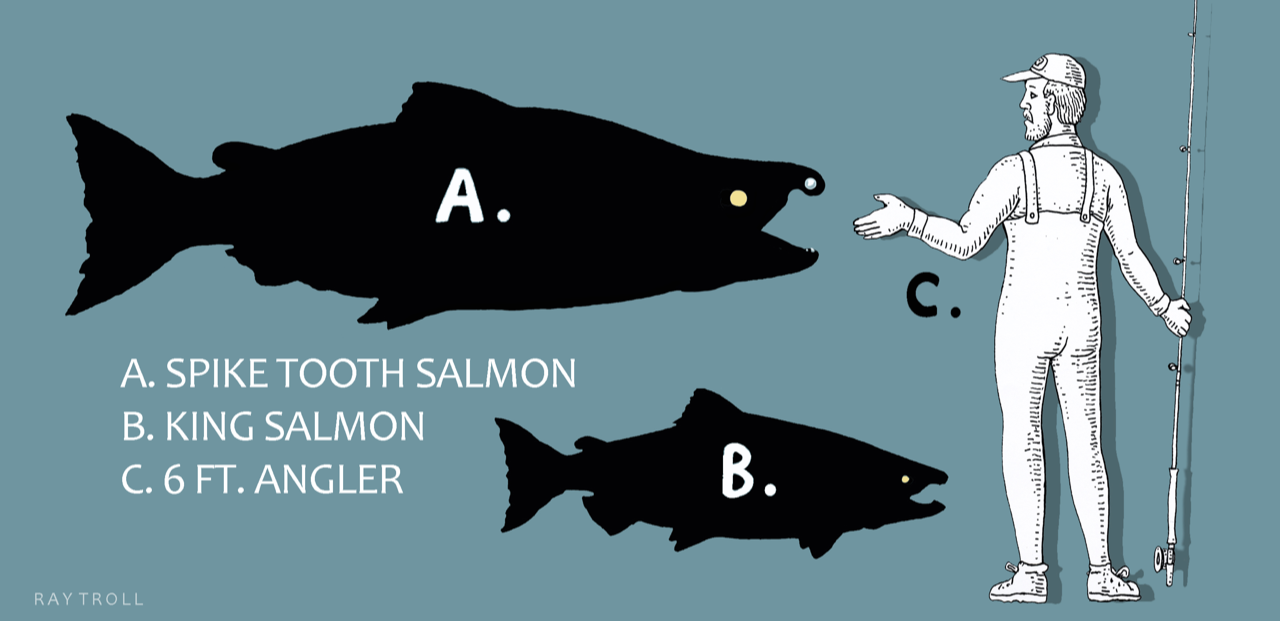

Today, Chinook are the largest living species within Oncorhynchus, the salmon genus, reaching up to five feet in length. But seven million years ago, a now-extinct species of salmon in the Pacific Northwest, O. rastrosus, would have dwarfed their modern relatives. The fish could grow up to nearly nine feet long—and that’s not even the most intimidating thing about them.

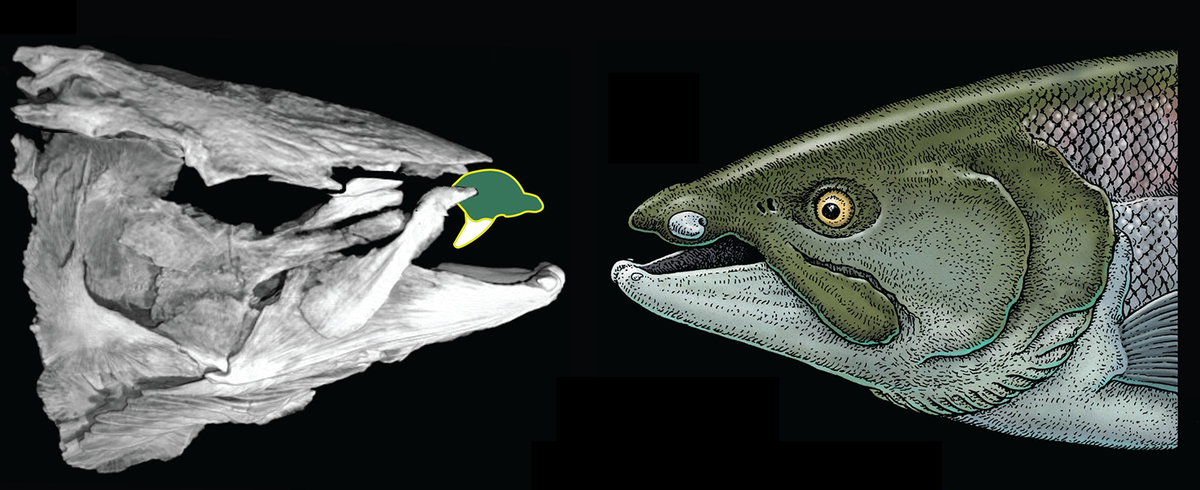

Previous research described the fearsome fish as having two enlarged teeth, earning them the nickname “sabertooth salmon.” Now, a new paper in the journal PLOS ONE shows that these teeth were more like tusks, protruding straight out to the sides from the tip of their jaws, earning them a new moniker: the spike-toothed salmon.

“I’m a little bit over six feet tall and that salmon is broader than I can reach from head to tail,” says University of Oregon paleobiologist and coauthor Edward Davis. “It’s an impressive animal. Thinking about trying to wrestle one of those on a fishing line is a difficult proposition.”

In the 1970s, researchers found the first fossil of the giant salmon species in eastern Oregon. To their dismay, the skull was crushed. The team made an educated guess, based on the anatomy of modern salmon, about how the ancient fish pieces fit together, including a “saber tooth” reconstruction for two fang-like fragments.

In 2011, Davis was approached by members of the North American Research Group (NARG), a collection of fossil hunters and amateur paleontologists. At the time, the site where the fossils had been found decades earlier was privately owned and off limits. But NARG members peeking through a fence believed that they’d spotted additional fossils at the site, and enlisted Davis to help them get a closer look. “That’s the benefit of all those volunteers and amateur paleontologists who are keeping their eyes peeled,” says Davis.

The club’s hunch was right. With the property owner’s permission, Davis and his team found additional bones in 2011 and 2014, including their holy grail.

Davis remembers the day in the lab that volunteer Pat Ward, going through the 2014 material, came running up to him, excited about what he’d just found: not one but two nearly complete skulls.

“We ran downstairs and sure enough, we had two skulls and they both had these sideways teeth,” says Davis. “Neither one of us had expected that. That was the moment when we realized that we had something special.”

The unique, tusk-like teeth protrude from the sides of the snout tip, curving slightly, like a weaponized mustache. They would have been useful for defense when making the perilous journey upstream, says Davis, but he thinks there may be more to the salmon’s story.

Among several modern salmon and related species, at sexual maturity only males experience structural changes to their jaws, an adaptation used for fighting competitors and defending females during spawning. However, Davis and his team found the unique, tusk-like features on both male and female giant spike-toothed salmon.

“Whatever explanation we can come up with for the teeth has to be something that would be useful for both males and females,” says Davis.

He suspects the salmon could have used the spikes “like elbows to clear out the space around them and get to the best spots.” Modern salmon behavior includes females digging nests, or redds, by pushing their snouts into the sand—if the ancient salmon did the same thing, Davis says, “By having these spike teeth, they’d actually be able to bulldoze out a wider furrow.”

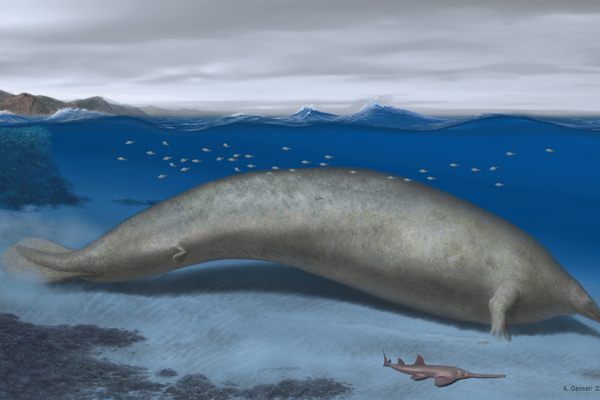

Alas, the reign of these giants wouldn’t last. While modern salmon are typically considered diet generalists, these ancient fish were specialized filter feeders. It’s possible that, as oceans cooled, the spike-toothed salmon were outcompeted by other, larger filter feeders, such as baleen whales. The last giant salmon disappeared five million years ago and, even as oceans warm once more, we won’t see their like again.

“Just because it warms up a bit, I don’t think we’re going to see spike-toothed salmon swimming around,” says University of British Columbia zoologist Eric Taylor, who was not involved in the study but is writing a book on salmon. The evolutionary processes that led to these wondrous “tusked” giants were complex and occurred over millions of years, and are unlikely to reoccur. But, adds Taylor, “There’ll be something else that none of us are going to be around to see.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook