Michigan Is Trying to Make Its Historic Markers More Accurate and Less Racist

It can take a lot of time—and some heavy bureaucratic lifting—to tell an honest story about a state’s past.

As a kid growing up in Michigan, Renée “Wasson” Dillard spent long days in the back seat of her family’s station wagon, watching the world blur by.

Back then, before the American Indian Religious Freedom Act passed in 1978, powwows and other Native American ceremonies and gatherings were often conducted in private—in basements or back rooms, or far out in farmers’ fields. So Dillard’s family—members of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians—would travel to these events, crisscrossing the state, driving south, or roving west.

Their literal journey was also a symbolic one. “We were on this journey as family to reclaim our traditional culture,” says Dillard, whose father and grandmother, born in 1898, had been in enrolled in Indian Residential Schools—part of a legacy of whitewashing Native communities and history. As a result, “there was [an] interruption in traditional cultural knowledge.”

On the road, Dillard’s family often pulled over at lookouts or rest stops to read the historic markers that dot the state. “Mom was kind of a history buff,” Dillard says. “And someone took the time to put them up, so we took the time to read them.”

When they studied the roadside signs, Dillard’s family hoped the text might help them weave together more threads of their history, which often received only a passing mention in textbooks. In the tribe’s territory around Harbor Springs, at least, “we pretty well understood the overall history,” says Dillard. “But we hoped the signs would carry some detail.”

Often, though, the opposite was true. In a roadside park on Highway 2—near the narrow Straits of Mackinac, where you can stand on the Upper Peninsula and gaze out at the lower, mitten-shaped one—they saw a plaque describing Lake Michigan. The sign was tall and wide, easy to see from a distance, and its tidy serif font accurately described the lake’s shape (elongated) and size (one of the largest in the world). But it also got a lot of things wrong.

According to the plaque, the lake was “discovered in 1634 by Jean Nicolet,” implying that no one had seen it before the French-born coureur des bois came across it in the 17th century. Then, as the sign tells it, it took another few decades before other European explorers gauged the “general size and outline” of the lake. Seventy-seven words marched across the plaque, and not one of them made reference to the Native communities that had navigated and fished the lake for centuries before Nicolet set sail.

That didn’t sit well with Dillard. “We were here,” she says. “We didn’t need it discovered. ‘Thank goodness for this French asshole [who] showed up to tell us that it was a lake.’ It’s just so ridiculous.” The sign had offended her since she was a kid. Even when she got older, she often thought, “‘Man, I’d like to take a war party up there and just cut it down.’”

Dillard, now in her mid-50s, never demolished the sign, but she did post a photo of it on social media this spring, pointing out the flawed, sparse, and offensive account and wondering how to amend it.

That’s what the state of Michigan is now grappling with on a broad scale. History is past, but it isn’t fixed: Descriptions are always products of their time, and when historians revisit old accounts and foreground voices and perspectives that had been muted, contemporary understandings shift. But while understanding of history are sometimes fluid, the metal markers that describe it are not.

Michigan is speckled with more than 1,700 gold-and-green historical plaques. Like their counterparts across the country, these signs make history plainly visible—but only to the extent that a single paragraph can encompass centuries of nuance, acknowledge several different perspectives, and hold up over time. It’s a tall order.

So now the state is taking up the task of telling its own story in a contemporary manner, rewriting the way its historic markers recount the past.

Custodians of historic sites grapple with complicated histories in various ways. They might topple a structure interpreted as a monument to racism, for example, as was the case when a mission bell was recently removed from the University of California, Santa Cruz campus at the behest of tribal leaders, who argued that it valorized the legacy of forcibly converting indigenous people to Christianity.

In other instances, site custodians—or even an entire town— might reckon with a thorny history that they hadn’t previously confronted at all. That’s the tack that a small town in Ontario, Canada, recently took when it planted Japanese cherry trees and installed plaques recounting the experiences of more than 150 Japanese-Canadian men who had been exiled from British Columbia during World War II and interned on farms to the east, in the agricultural community now known as Chatham-Kent. Though one of the buildings that had held the relocated men is still standing at an intersection in the town, locals rarely acknowledged the uncomfortable history it represents.

“I don’t think it’s very well-known,” Jeff Bray, a local manager of parks and open spaces who worked with the National Association of Japanese-Canadians on the historic markers, told the CBC just before the new placards were placed in the ground. “I never learned it in school, and I know my kids didn’t either.”

Rewriting the account of an event that previously relied on a single narrative might involve amplifying voices that weren’t originally quoted. It might also mean striking offensive, imprecise, or outdated language. In recent months, several U.S. cities have done exactly that. Memphis, Tennessee, and Savannah, Georgia, for example, recently unveiled new markers celebrating their regions’ diverse history by putting up markers to commemorate a community center founded in the 1920s by Chinese immigrants and Chinese-Americans, and 19th-century African-Americans who built lives for themselves along Savannah’s southeastern marshes. Meanwhile, Yarmouth, Maine, recently removed a plaque that referred to Native Americans as “savage enemies.”

In Michigan, the edit will be sweeping, and time-consuming.

Placards have been going up around the state since 1955, and “our concept of history and what should be on the markers has changed since then,” says Sandra Clark, director of the Michigan History Center, which oversees the process.

In Michigan, a historic marker is born when a community member or group nominates a site and submits an application form—along with primary-source documentation, maps, photographs, and a $250 application fee—to the Michigan Historical Commission, a governor-appointed body. If a site passes muster with its historic bonafides, the commission works with the nominator to hash out the text, then the nominator ponies up money to pay for it. (Prices range from $1,900 for a small marker to $3,750 for one that stands four-and-a-half feet tall, with double-sided text.)

It hasn’t been a secret that at least some of these historic markers—especially the oldest ones—contain slurs, or only detail a small sliver of history.

“There’s little to no Native voice, female voice, or African-American voice,” says Eric Hemenway, director of archives and records for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, and a frequent collaborator on Historical Commission projects. The text on the markers often reflects “history told through a very specific lens.”

That lens, of course, has usually been white and male. But until now, there hasn’t been a mechanism for assessing whether the markers, installed decades earlier, need a closer look.

They got one after Dillard sent her snapshot of the Lake Michigan marker to a friend who works at the state Department of Transportation (DoT), which manages the property the marker is on. That friend passed the image along, and the soon donated money to redo it and three other signs about the Great Lakes on DoT land, Clark says. (One marker celebrating Lake Huron, installed in the 1950s and also slated for revision, notes that the lake was “the first of the Great Lakes seen by white men.”) Clark hopes that the new signs will be in place by 2020.

Meanwhile, the conversation about the Lake Michigan marker is part of a larger movement: a more holistic accounting of the story the markers tell about the state. “If you start changing one or two, you’ve got to look at all of them,” Hemenway says. That might start by “finding out which are the worst of the worst, so to speak, and which we need to change right away.” But each and every marker will eventually have to be scrutinized. There’s no shortcut for that, Hemenway says: “You just have to grunt through and read the text.”

The statewide reassessment will also involve revisiting stories that may have been previously overlooked. It’s still in the very early stages, but as the work progresses, Clark plans to seek private funding to host events in local libraries and historical societies, where residents will be invited to tell the commission “what isn’t here, and what might offend some people about what is here.” In service of this goal, the commission is also reconsidering what constitutes a usable primary source.

“Not all groups were privileged to have folks writing down what they were doing, what they were thinking,” Clark says. Church programs and other ephemera likewise hold a wealth of information about communities and events that weren’t necessarily covered in newspapers or formal reports.

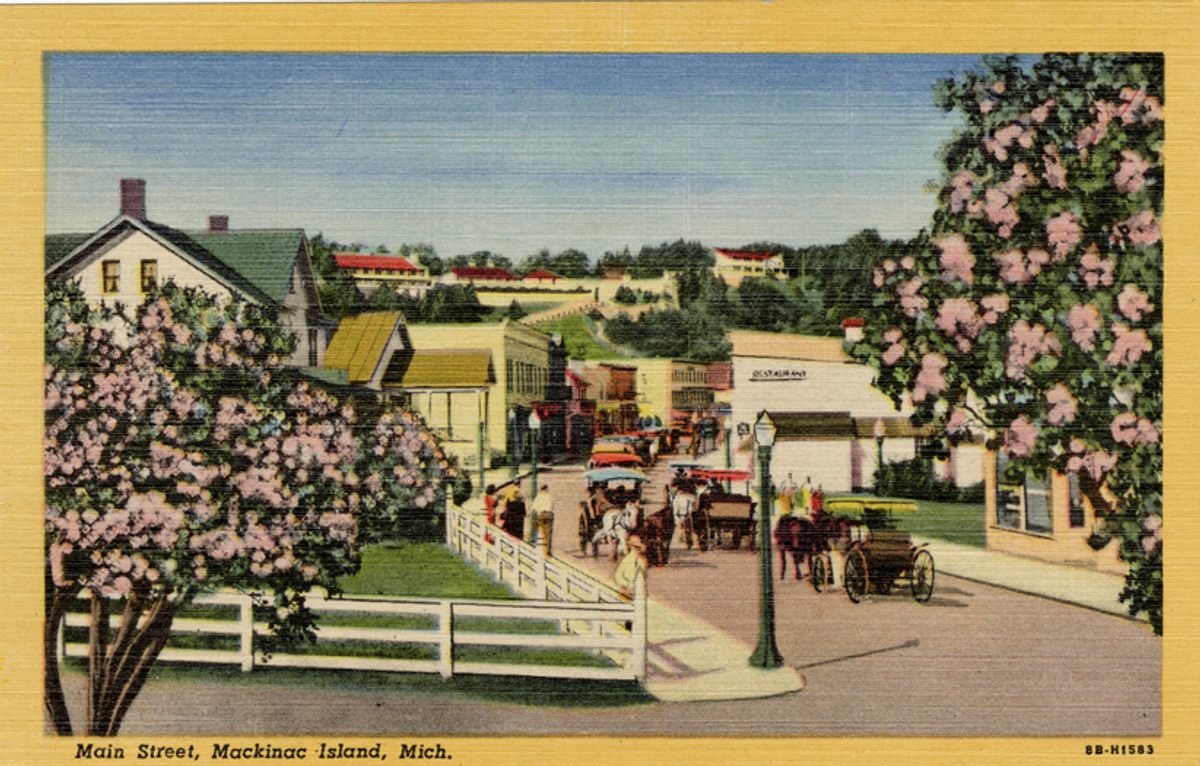

For precedents, teams drafting new text might look to Mackinac Island, a landmass between the state’s upper and lower peninsulas. A few years back, Hemenway worked with Phil Porter, director of the Mackinac State Historic Parks, on a series of signs scattered across half a dozen turnouts along an eight-mile trail.

“The purpose was for us to do a more accurate job of telling the story of Native Americans’ centuries-old connection to Mackinac,” says Porter. This entailed grappling with old conflicts, treaties, and water issues, and bringing the story up to the present day, with photographs of tribal people fishing on the land of their ancestors. “I didn’t want to leave us in the past,” Hemenway says. “In the U.S., Native people tend to drift out of the [mainstream] story in the mid-1800s, and we’re gone.”

Beyond Hemenway and Porter’s sign project, there’s also an effort to revisit the stories told about the Biddle House, an 18th-century home on the island. The house, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is named for former owner Edward Biddle, a prosperous fur trader. Key to his professional success were the relationships and acumen of his wife, Agatha Biddle, a woman of Odawa and French descent. The marker references Edward by name, but Agatha is only invoked indirectly, as “his Indian wife.”

“In my opinion, Agatha was more important,” Hemenway says. She was a chief of her tribe, and known for her philanthropy and caretaking of ailing kids—acts for which she was posthumously inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame in 2018. “From reading the marker today,” Hemenway adds, “you wouldn’t even know her name.”

That will soon change.

“We have been working with our own staff and other researchers to try and flesh that story out,” says Porter. Clark says she hopes “a new marker will give Agatha her due,” and the House will be turned into a Native American history museum, scheduled to open in 2020. The Historical Commission has also begun evaluating other markers on the island that need a red pen, prioritized which should come first in the editing queue, and recommended that a group of historians and other experts work together to draft and review any new text.

As the statewide project gains speed, Dillard and Hemenway note, it will be crucial to connect with members of the communities that the markers describe. “Reach out to the people that you’re telling the story about,” Hemenway says. “If you have a story about Natives, you talk to Natives.” In history books, Native stories are “portrayed as [they were] observed, rather than how [they were] experienced,” says Dillard, who teaches traditional weaving and other fiber arts that help indigenous people reconnect with their heritage.

Hemenway believes that this failure to learn from firsthand knowledge contributed to the text’s inaccuracies and omissions. “There was no reaching out to these groups in the ’50s and ’60s whatsoever,” he says. “If there would have been, the narrative would have been completely different.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook