The Miss Subways Pageant Charted the Highs and Lows of 20th-Century Feminism in New York

From a 1940s beauty queen to a 2017 performance artist.

The winner of the 1940 Miss Subways beauty contest was Mona Freeman, a fresh-faced teenager who went on to appear in more than 20 films. Its 2017 victor was a 61-year-old performance artist, who achieved some notoriety for a public appearance in a Brooklyn art gallery in which she sat naked on a toilet.

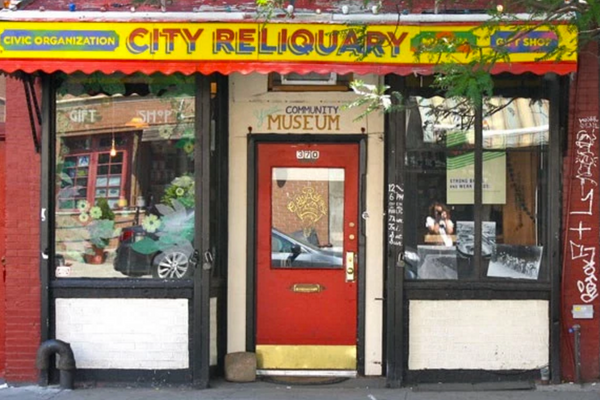

This contest intitially ran from 1941 through 1976 under the auspices of the precursors of the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), and was resuscitated as a pageant by the MTA in 2004 as “Ms. Subways.” This year it has returned again, but it’s nothing to do with the MTA. This incarnation, held at the City Reliquary in late September, was a protest against everything the contest had once stood for: beauty contests, commercialism, the glory of the MTA, even femininity itself. Instead, the organizers welcomed contestants of all genders, encouraged viewers to join the Riders Alliance advocacy group, and proclaimed 2017 the subway “Summer of Hell.”

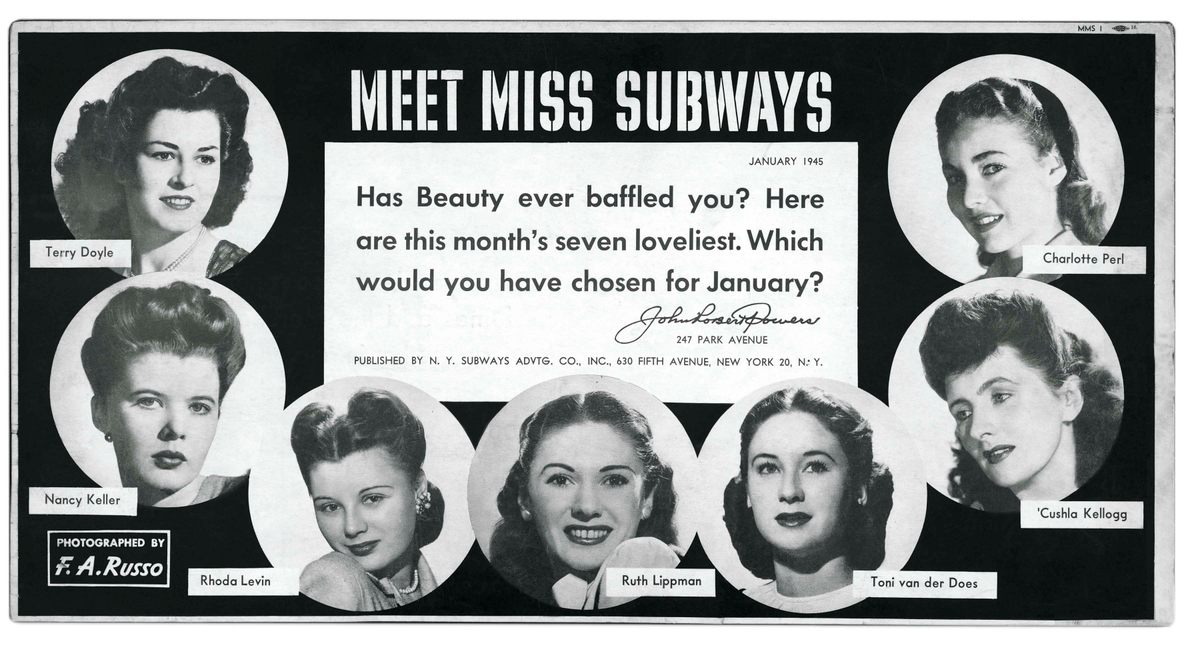

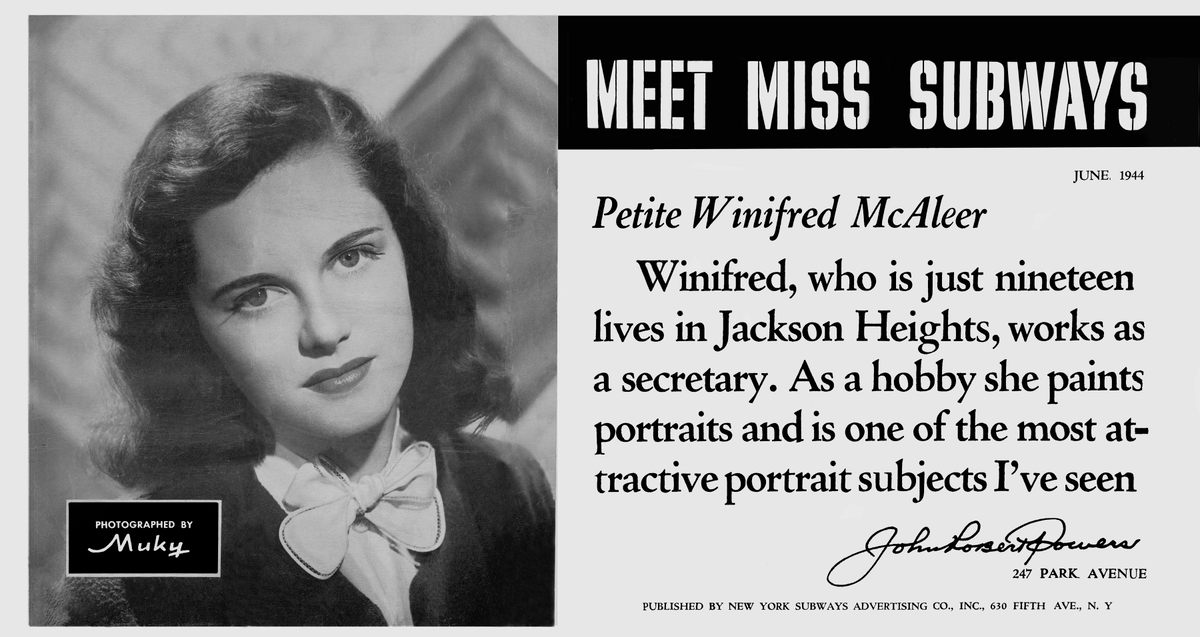

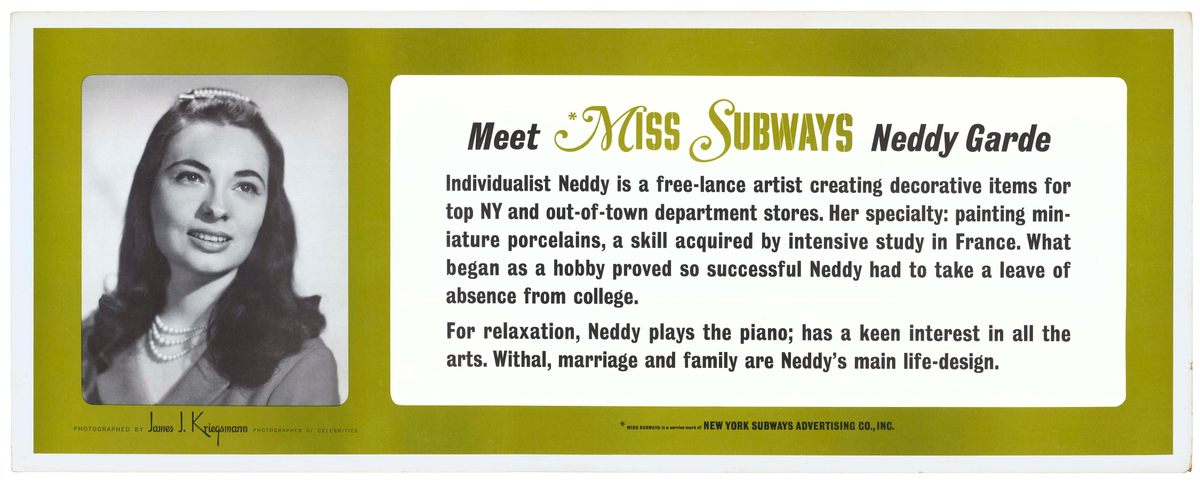

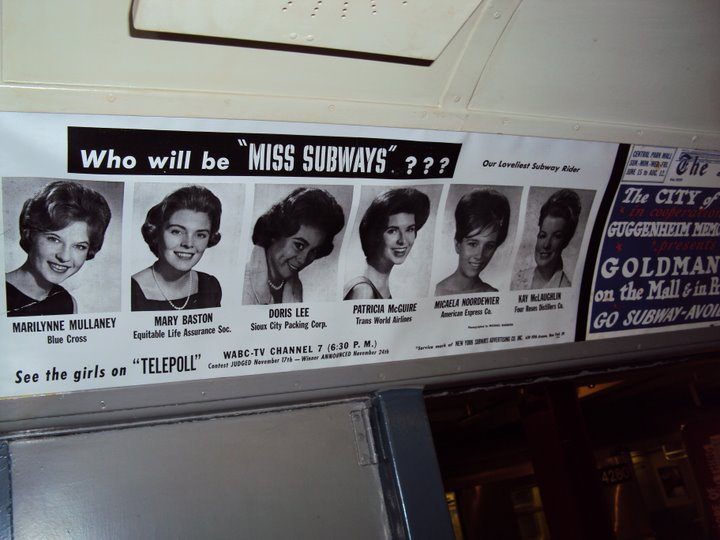

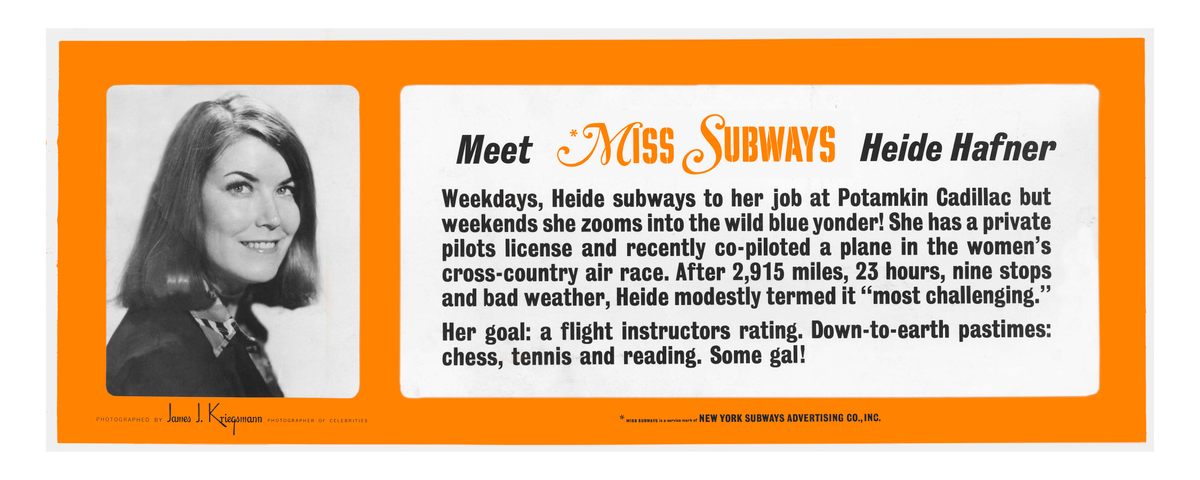

In its origins, the Miss Subways competition (it was more contest than staged pageant) was designed to draw straphangers’ eyes up to smiling faces of beautiful women and then, presumably, over to advertisements for cigarettes or chewing gum. Each month, at the beginning at least, a new queen was crowned, and each month a new poster was made, with a caption highlighting the winner’s hobbies, career, dreams, and, often, marital status. The copy was written by ad men, and sometimes stretched the truth dramatically. At first, the winners were chosen by the advertising company that ran the contest, often from women who wrote in or via a tap on the shoulder, as in the case of the stunning young manicurist at the Waldorf who did some ad man’s nails. Then, in 1960, members of the public were allowed to vote for a winner from among six finalists. Answers on a postcard, please, and no more than one per person.

Miss Subways was the pretty girl next door, with aspirations to marriage, family, and a trip to Bermuda. But she reigned over the wilds of the IND, BMT, and IRT. “They were a snapshot of typical New York working women,” says Amy Zimmer, journalist and author of Meet Miss Subways: New York’s Beauty Queens 1941–1976. “These were working-class women, accessible and inspirational.” They were women whom other women felt they could be, and whom men felt they could date. (Winners often received marriage proposals, flowers, and, once, a three-foot lemon meringue pie.)

The beauty contest tracks the highs and lows of 20th-century, and now 21st-century, urban feminism, says Kathy Peiss, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania who contributed an essay to the book. She writes, “Miss Subways opens to view hidden histories of everyday life in New York that touch upon the changing ideals and aspirations of women, the struggle for civil rights, and the rise of a modern culture of beauty, consumption, fashion, and image-making.”

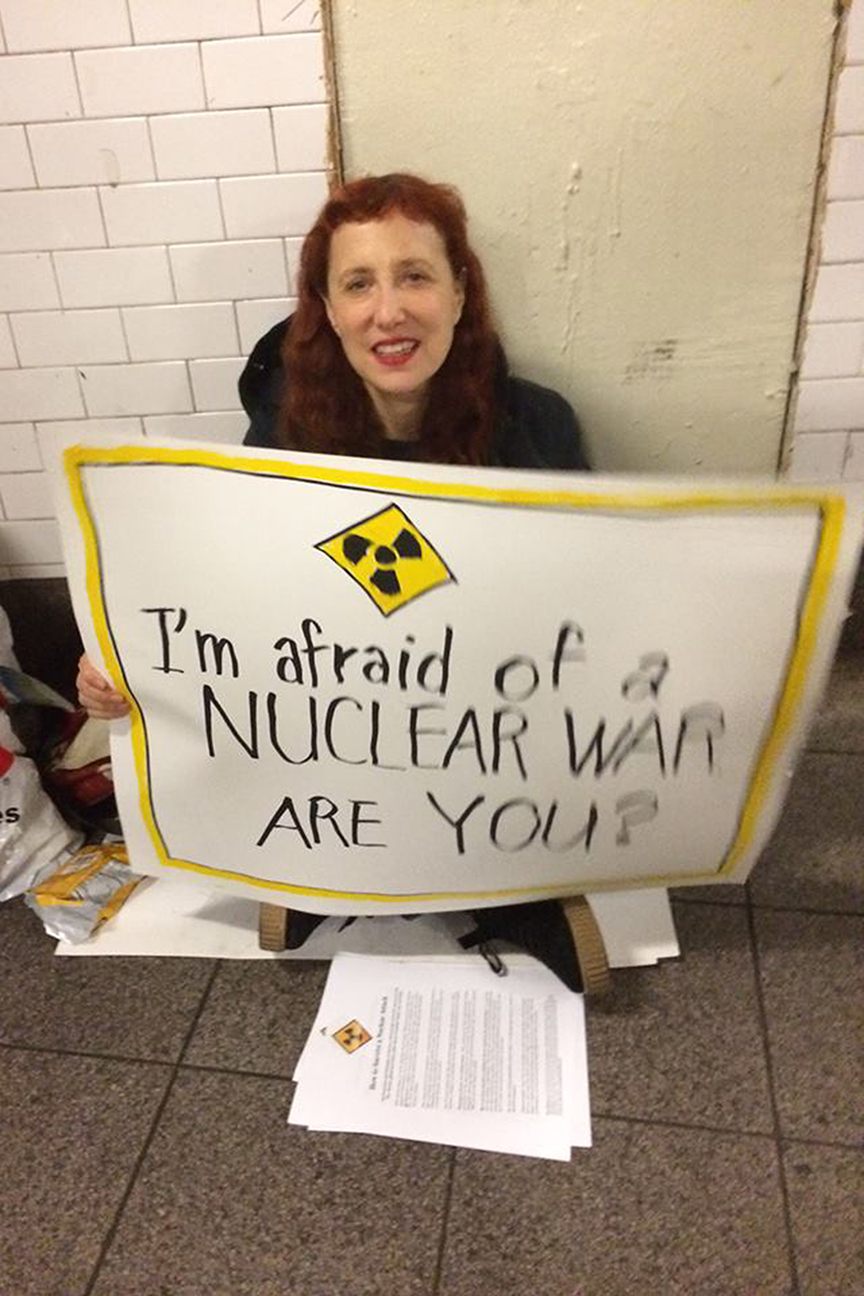

As the competition began, women were charging into the workforce with the beginning of World War II. By the 1950s, they felt the siren call of the suburbs and homemaking. The pageant winners evolved with the times: women who traveled alone for fun, or took to the skies as air hostesses and, in the case of the 1976 winner, a pilot. But it was the rise of second-wave feminism and the 1970s fiscal crisis that seemed to have left the pageant for dead. Soon women were loath to ride the subway, which was thought of as very dangerous. Lisa Levy, the performance artist and 2017 winner, was born within a few years of when the last Miss Subways winner was born, and saw many of these changes first hand. “I have seen a lot,” she says. “I try to really stay in the moment about New York. It changes and evolves, in good ways and not so good ways.”

In 2012, Zimmer released Meet Miss Subways with photographer Fiona Gardner, supported by the New York Foundation for the Arts. For the book, they tracked down as many of the winners as they could, and interviewed them about their lives after the pageant. Initially, winners held their titles for a month, then two, and finally six. Some had divorced and remarried, moved away and could not be found, or passed away.

Some spoke of the contest with derision, others considered it a crowning achievement. Dorothea Mate Heart, who won in 1942, believed that her win went beyond “a pretty face.” “I was a volunteer with the Office of Emergency Management. I think I was a role model.” As she recalled in the book, “It may be superficial, because it’s only looks, but it has helped me over the years.” Meanwhile, Enid Berkowitz Schwarzbaum, who won four years later, pooh-poohed the whole thing. “I don’t regard being selected as an accomplishment,” she told Zimmer. “I think someone who’s really done something, who’s really given something or made something of himself, that’s really an accomplishment.”

Winners in the 1940s were, like many women at the time, involved in the war effort. Singing “triplets” (actually twins and another sister) Dawna, Doris, and Dorothy Clawson claimed to have “sung at every camp within 50 miles—but their hearts belong to [the] Navy.” Others said they passed the time writing letters to “boy friends” serving far away. In the 1950s, women began to try to reconcile professional aspirations with family life. In 1950, Patti Freeman mentioned as her ambition “success in both theater and marriage,” and in 1951, Frances Carton said she hoped to be “an interior decorator but chose marriage.”

Even when Miss Subways winners had, and had achieved, lofty career goals, their press coverage was depressingly sexist. An early Asian-American winner, 1954’s Juliette Rose Lee, was “a Physics technician at Columbia U. Ambitious to be a physicist.” Lee went on to achieve considerable success in particle physics, but at the time was described by gossip columnist Walter Winchell as “a china doll, most tempting Chinese dish this side of chop suey.”

To keep the competition relevant, the competition’s administrators marshaled the forces of feminism. When Bernard Spaulding, sales director for New York Subways Advertising, took over the competition in 1960, he stated that he would not be prioritizing competitors’ good looks. “Prettiness is passé,” he said. “It’s personality and interesting pursuits that count.” Other kinds of political action were woven into the competition as well. Berkowitz’s entry was motivated at least in part by an attempt to prove that someone with an obviously Jewish surname could not win. “I did it as a test,” she recounted later. But New York had a large, and growing, Jewish population, many of whom regularly rode the subway and looked up at those advertisements by her face.

In the late 1940s, nearly 10 percent of New Yorkers were black. The first black Miss Subways, Thelma Porter, won in 1948, 35 years before the first black Miss America. Black newspapers in the city had been campaigning for an African-American Miss Subways, and New York Amsterdam News columnist Dan Burley observed, in 1942, that “Harlem’s younger female set is mad as hell about the implied insult to them in the subway cars.” Like contemporary ad men, the minds behind Miss Subways saw that there was money to be made in embracing diversity. The last winners in the 1970s reflect the fact that by then almost half of New York was non-white.

Some winners, who dreamt of more than a secretary’s pink-collar opportunities, hoped that a win could get them discovered and launch a glittering career, says Zimmer, “whether in modeling, or acting, or on-stage, singing.” For one contestant it did, sort of. Ellen Hart Sturm, who won in 1959, went on to open all-singing, all-dancing Ellen’s Stardust Diner in midtown Manhattan. Its walls are lined with the advertisements of former winners. “My fantasy on the Miss Subways poster said I was going to be a famous singer,” she related to Zimmer. Instead, she got married at 21 and was pregnant “right away, because in those days we knew so little about sex.” The first legal contraceptive pill went on the market the year after her win, and two years before she got pregnant. “I didn’t work hard enough to be a star,” she said. “You have to give up everything.”

The final winner, in 1976, Heide Hafner, told Zimmer: “I didn’t want to be a dopey beauty queen. I just wanted to promote aviation. It was my first love, more or less.” By then, the competition was decided by public vote, so she bought and stamped 500 postcards, which she gave to people she met. “By that time, Miss Subways was losing its glamor. But we didn’t want the glamor scene any more,” she said. “I was happy with the results, just to know I got aviation out there.” By then, the subway was at a low ebb, with the MTA saddled with a $500 million deficit.

A scathing New York magazine feature that year described how winners were mortified to see themselves defaced (“sex organs [balloon] from her ears”) on the graffiti-covered cars, and hated the advertising copy and chintzy bracelet they received. Men they met asked them questions about the “size of their tunnel” or doodled obscenities coming out of their mouths on the signs. The winners would have been happier to just get a subway pass instead. The days of aspiring to the “glamor” of ruling New York’s underground (often from a distance, the 1941 winner had never handled a pole or hung from a strap) were over. Within months of the publication of the magazine story, the competition was over.

Two years after that, Lisa Levy, who spent her early years in the city, had returned to New York after more than a decade away. Following an incident with a pickpocket, when she pushed to get off the train and hit with a newspaper, she suffered a panic attack and was unable to take the subway for years. In the time since, Levy worked first as a commercial illustrator and then an art director in advertising for a quarter-century. She’s also launched a career as a performance and conceptual artist: Levy sold “Studio 54 Reject” T-shirts to those who failed to get in to the famously debauched club, starred in a documentary about not wanting to get married, and launched an advice show, Dr. Lisa Gives a Shit, on Radio Free Brooklyn.

This year, she decided to enter the new incarnation of the Miss Subways pageant. Unlike their forebears, the 2017 entrants at the City Reliquary did not, generally, appear to be seeking husbands in the burbs or careers in Hollywood—at least not as traditional leading ladies. Filmmaker Dylan Mars Greenberg writhed on the ground, shoveling dirt into her mouth, in a vigorous display of how to handle a public masturbator (disturbingly not-all-that-rare on the subway). Drag queen Glace Chase, who gives tours of the city, sported a luxuriant merkin over her fishnets. And, perhaps most bizarrely, “Sundae Fantastique,” aka Carrie-Anne Murphy, dressed up as a kind of haute subway rat to perform a crying soundscape over the distant strains of a 3 a.m. Q train that would never arrive. In the 1970s, women felt the pageant pigeon-holed and objectified them. At the City Reliquary, beneath a great rusted ladder that rose into the air like a ship’s mast, rigged fairy lights illuminated a ramshackle crew of all genders and all ages. Pigeon-holing of any kind would have been impossible.

Levy declared that she wanted to be the first postmenopausal Miss Subways, to communicate something important about aging, femininity, and the discomfort women are supposed to feel in their changing bodies. “I feel really passionate about the lack of consciousness around women’s sexual currency,” she says. “Women need to own that, and we need to take charge of that ourselves. I don’t think we’re ever going to have equal rights unless we own our value, in getting older, for better or for worse.”

Sexual currency was not among the criteria for this year’s pageant, which prized charisma, the quality of answers to questions, and performance. In a long red dress, Levy gave a monologue about her experiences on the subway, while her husband (she got married after all), artist Phillip Buehler, beamed at her from the audience. After she was crowned, he watched recorder-clutching journalists and flashing cameras envelop his wife. “I guess I’m Mr. Subways now,” he said, looking almost dizzy with pride. “The First Subways.”

There’s something fitting in the idea that a woman who was once too afraid to take the subway late at night now “rules” over it. “You were really judged, on how cool you were, on whether you would go out and take the subways at all hours of the day or night, or go over to Avenue B or C,” Levy says. “I really was a nerd, I was afraid of that, and it limited my cool factor. I wasn’t really that cool, because I was truly afraid.” She barely remembers the original version of the beauty contest, despite having ridden the train at the time. “I don’t have a really strong memory of it,” she says, “but it’s not unfamiliar, either.”

For Levy, like so many others, Miss Subways was just woven into the fabric of New York’s underground life—a fleeting piece of pop culture and an artifact of the lives of women in a modern city. Levy is going to wear her crown for a year—presumably not all the time, but she is a performance artist, so who knows?—and then, the folks at the City Reliquary suggest, pass the title on to the new winner.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook