How a Librarian and a Food Historian Rediscovered the Recipes of Moorish Spain

A new cookbook is a translation of a rare, 13th-century volume.

“Take large fine-tasting carrots, lightly scrape their skins, cut them in half lengthwise, and then split each half into two pieces.”

For centuries, that’s as far as any cook could get when preparing “A dish [of carrots in sauce]” from Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī’s Fiḍālat al-Khiwān fī Ṭayyibāt al-Ṭaʿām wa-l-Alwān (Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib), a cookbook composed in Tunis around 1260. The rest of the recipe (more on that later), together with dozens of others, disappeared sometime after the late 1600s.

Most of the cookbook’s 475 recipes survived in copies. Yet that maddeningly incomplete carrot recipe, along with missing chapters on vegetables, sauces, pickled foods, and more, left a gaping hole in all existing editions of the text, like an empty aisle in the grocery store.

That was until July of 2018, when the British Library’s curator of Arabic scientific manuscripts, Dr. Bink Hallum, was cataloguing a text on medieval Arab pharmacology in the library’s collections.

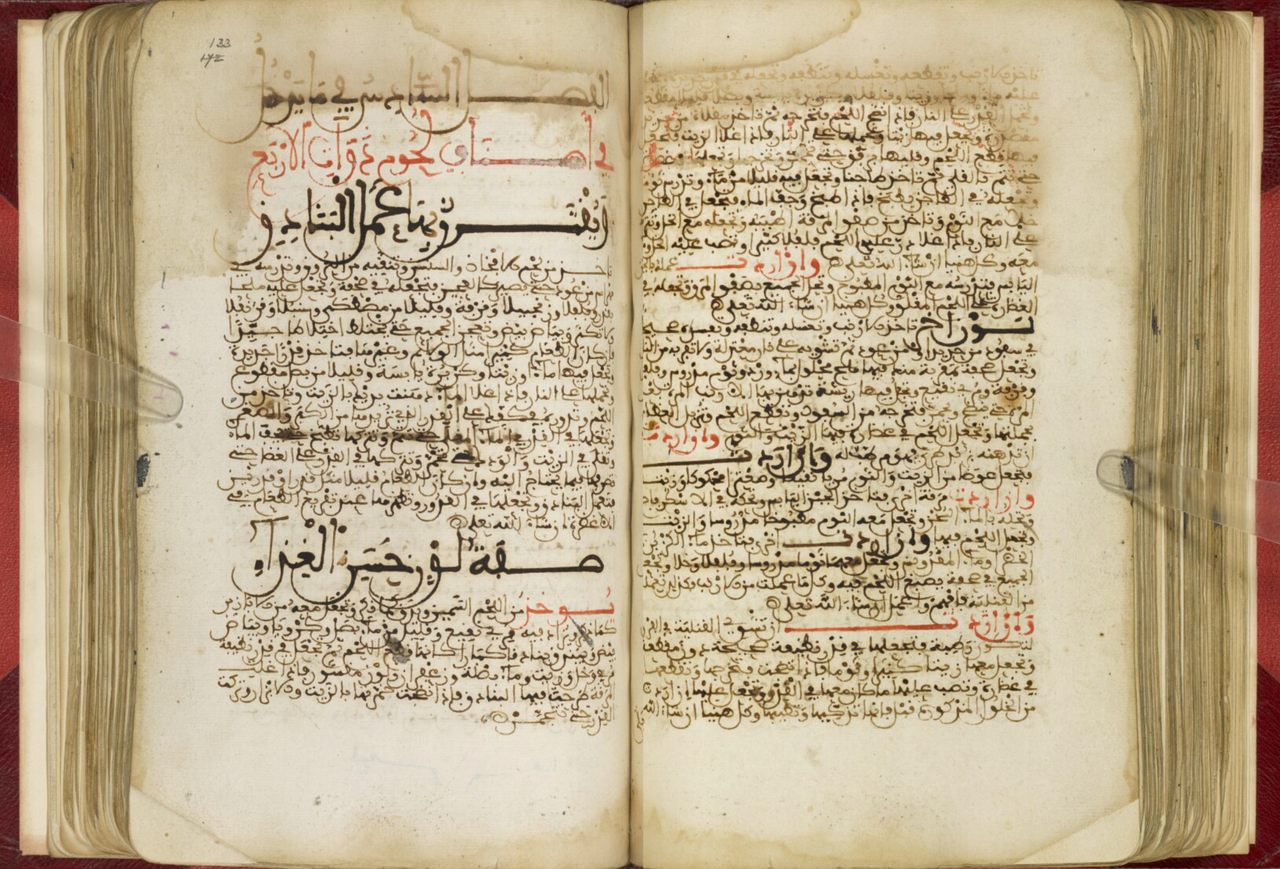

“I was very surprised when I found that the manuscript also contained a very long fragment, a little over 200 pages, of a cookbook,” says Hallum. What he had stumbled upon was a nearly complete copy of the Fiḍāla dating to the 15th or perhaps 16th century, making it the world’s oldest extant copy.

Still, because the document lacked a title page, its identity remained a mystery. Acting upon a colleague’s recommendation, Hallum eventually sent a link to the manuscript to food historian Nawal Nasrallah, who, as it happened, was busy translating one of the incomplete copies of the Fiḍāla from Arabic into English.

“It was just like a gift from God,” says Nasrallah. “I hated the idea that I was working with an incomplete book and was coming nearer and nearer to the missing parts.”

In addition to the title page, the table of contents was also absent from the British Library copy. Yet Nasrallah immediately realized what she was looking at.

“I knew right away. I was reading the manuscript on the screen, and I saw that there they were, the missing recipes,” says the Iraqi-born Nasrallah, an experienced translator of historic culinary texts from the Arab world.

With this new material in hand, including 55 missing recipes, she was able to piece together the first full English translation of al-Tujībī’s Fiḍāla, which was published this September by Brill. It remains one of only a handful of surviving cookbooks from Moorish Spain, an era when food was deeply intertwined with those traditionally taboo dinner-table topics: religion and politics.

From roughly 700 to 1200, most of Spain was under Muslim rule. Christians and Jews were free to worship, and observe their dietary customs, in an atmosphere of coexistence known to history as Convivencia. Whereas Jews and Muslims shared food prohibitions, such as pork, commonly eaten by Christians, cooks from all three religions enjoyed many ingredients first brought to the Iberian peninsula by the Arabs: rice, eggplants, carrots, lemons, sugar, almonds, and more.

“Even couscous, widely seen as one of the most indicative items among ‘Muslim’ foods, was also eaten and enjoyed by Christians in late medieval and early modern Spain,” observed the late scholar Olivia Remie Constable in To Live Like a Moor.

This was the age of al-Tujībī, a well-educated scholar and poet from a wealthy family of lawyers, philosophers, and writers. As a member of the upper class, he enjoyed a life of leisure and fine dining which he set out to celebrate in the Fiḍāla. Even if many of the recipes were too daunting for most cooks, al-Tujībī promised that they would “rarely fail to please with their novelty and exquisiteness.”

But starting around 1200, the high cuisine that al-Tujībī loved faced extinction as the tolerant spirit of Convivencia began to erode. Christian armies marching south gradually captured the city-states of al-Andalus (Andalusia), heartland of Muslim Spain, in a campaign known as the Reconquista. By 1492, many Jews had either been massacred or expelled from the peninsula, while Muslims faced the same fate a century later. Those remaining were hunted by the Inquisition and forced to either convert, which meant openly adopting a Christian diet, or face expulsion or even death.

Many reluctant Jewish converts (Conversos) and their Muslim counterparts (Moriscos) publicly worshipped as Christians while practicing their true faiths behind closed doors, including those of the kitchen.

“Food became a marker of identity,” says Ana Gómez-Bravo, a professor of Spanish and Portuguese Studies at the University of Washington.

“We know from Christian records that there was a lot of surveillance of who cooks the food, what ingredients go into that pot, and also who is present while the food is being prepared and consumed,” says Gómez-Bravo.

This level of scrutiny spawned Jewish and Islamic “crypto-cuisines,” foods prepared according to religious custom but intended to fool the authorities, such as faux chuletas (pork chops), which were actually thick slices of fried, egg- and milk-soaked bread.

“Conversos would throw an actual pork chop on the fire, to have the scent permeating the house, but were eating these things that were really French toast,” says Genie Milgrom, a descendent of conversos from Fermoselle in Spain’s Zamora region and author of Recipes of My 15 Grandmothers, a collection of family recipes dating back to the time of the Inquisition.

While much of this persecution occurred after al-Tujībī’s time, by 1247 he recognized that to remain a Muslim in Christian Spain was untenable. So at the age of 20, he and his family fled the southeastern city of Murcia with multitudes of Andalusi refugees headed for Islamic North Africa, known to Arabs as the Maghreb.

Now impoverished, he ended up in the port city of Bijāya, in what is now Algeria, where he picked up what amounted to temp work as a scribe for the ruling Hafsid dynasty. By 1259, he settled in Tunis where he began writing the Fiḍāla, at the age of 33, and lived there until his death in 1293.

While he wrote other books on history and literature, only the Fiḍāla survives. Its composition, says Nasrallah, was an exercise in culinary nostalgia, a wistful look back across the Strait of Gibraltar to the elegant main courses, side dishes, and desserts of the author’s youth, an era before Spain’s Muslims and Jews had to hide their cultural cuisines.

“His aim was to preserve the beautiful cuisine he grew up on. He was seeing everybody fleeing Andalusia and was afraid that sooner or later people would forget this cuisine that he knew and enjoyed,” she says.

When flipping through the 600 or so pages of the Fiḍāla’s recipes, their “novelty and exquisiteness,” as al-Tujībī characterized them, quickly becomes evident.

In tūma (eggplants “Looking Like Ostrich Eggs”), whole peeled and boiled eggplants are arranged vertically in a casserole topped with grated cheese, garlic, olive oil, and chopped walnuts.

Somewhat less elaborate, though no less self indulgent, were the breakfast treats mujabbanāt, fritter-like balls of fried semolina dough stuffed with cheese. Mujabbanāt spread to the rest of the Arab world where they were commonly served soaked in honey. Yet al-Tujībī specified that those “who want to serve mujabbanāt the way Andalusis do, [i.e.,] plain, without drenching them in honey” should place them on a platter, “sprinkle them with Ceylon cinnamon, pounded aniseeds, and sugar,” and serve with “a small vessel filled with honey in the middle of the platter” for dipping.

The book also includes less laborious recipes such as the long-lost carrot recipe which calls for boiling the pieces until tender, browning them in olive oil, and simply finishing them with vinegar, garlic, and a sprinkle of caraway seeds.

Throughout, al-Tujībī doesn’t hide the politics behind the book, nor his fondness for the cuisine of his homeland.

“[I]n the field of cooking and whatever is related to it, Andalusis are indeed admirably earnest and advanced,” he wrote. They create “most delectable dishes, and in spite of the constricting limitations of their borders, and their proximity to the abodes of the enemies of Islam,” by which he meant the steadily encroaching Reconquista.

While the “enemies of Islam” no longer hammer at Andalusia’s borders, some modern chefs are looking to its rich culinary past for inspiration, embracing and recreating dishes al-Tujībī himself might recognize.

After honing his kitchen management skills in al-Tujibi’s hometown of Murcia, fellow Andalusian Paco Morales returned to his hometown of Cordoba to open Noor in 2016. The restaurant’s menu is entirely derived from the Arab cuisine of pre-Reconquista Spain, including the Fiḍāla. (Dedicated to historical accuracy, Morales eschews using New World ingredients that were unknown in medieval Spain, such as chocolate, opting instead for carob in his “Almoravid carob” ice cream.) And at La Vara, in Brooklyn, chef-owner Alex Raij says menu items such as berenjena con miel (crispy fried eggplant served with labneh and honey), garbanzos fritos (fried chickpeas), and her almond torta Santiago reflect “the push and pull” of Andalusia’s Sephardic (Spanish Jewish) and Islamic culinary past, if not al-Tujībī’s very own story.

“La Vara imagines what Spain’s regionally specific dishes would look like if these [exiled] communities returned from the many parts of the world they left,” says Raij.

While al-Tujībī never saw his beloved al-Andalus again, thanks to the discovery of a 300-year-old clerical error, all of his favorite recipes have now returned home.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook