Every Time They’re Found, Underwater Volcanoes Just Burst With Life

New discoveries off the Chilean coast include dozens of species new to science.

I have not been to the bottom of the ocean, but I’ve spoken to a fair number of scientists who have, and no two chronicle the experience in the same way. I think the most memorable comment came from a seafloor geologist, who described the slow descent into the abyss as akin to “being an astronaut in reverse.” That stuck with me—the thought of heading into the watery underdark, enclosed within a cramped capsule, frequently enveloped in an eerie quiet.

There is, of course, (at least) one key difference between being an astronaut and an aquanaut: Space, at least the part of it we’re able to experience, is lifeless. But every single time an aquanaut heads into the sea—either in person or using a robotic envoy—life explodes into view. It was no different during a recent expedition off the coast of Chile, when scientists cruising above a nearly-1,800-mile-long chain of submerged volcanic mountains found a zoological bastion—home to more than 100 newly discovered species, from spindly lobsters to coruscating fish.

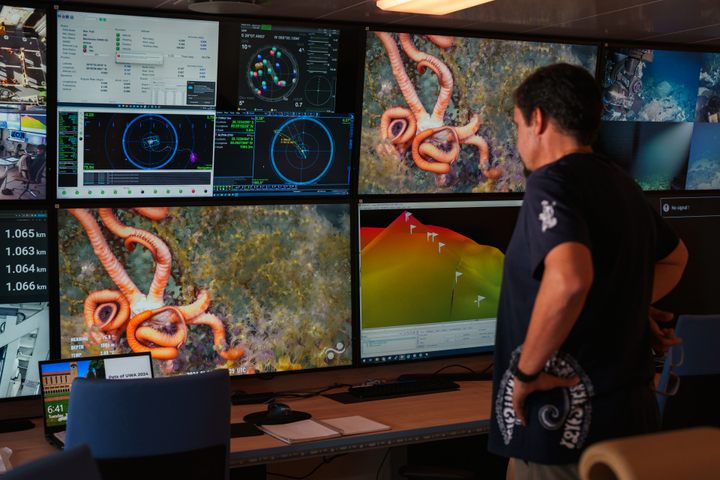

The expedition—operated by the United States–based nonprofit Schmidt Ocean Institute, and commanded by Javier Sellanes, a marine biologist at the Universidad Católica del Norte in Chile—didn’t opt to send fragile humans into the depths. Instead, while aboard the research vessel Falkor (too), they deployed SuBastian, a remotely operated submariner armed with a suite of scientific instruments.

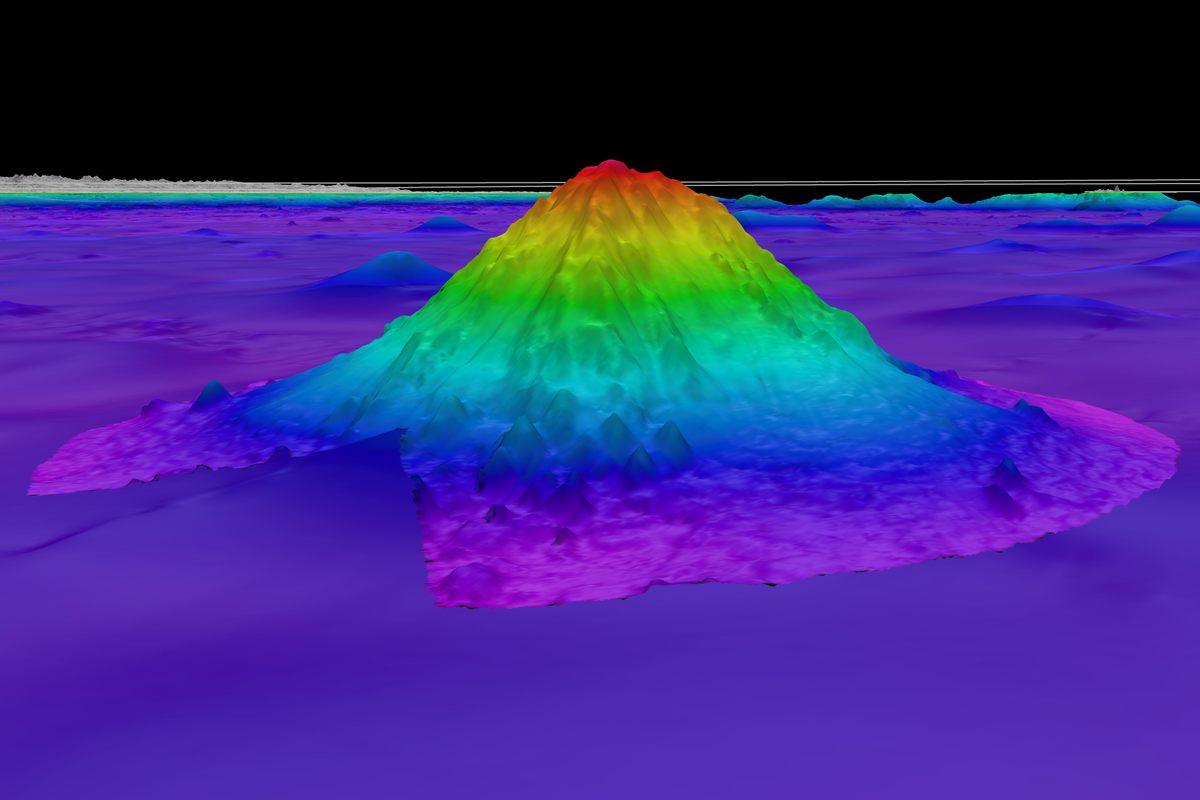

In recent months, the mission spied four newly described seamounts—underwater protuberances that are often extinct volcanoes—in Chilean waters. All four were vertiginous; one of them, rising almost 12,000 feet from the seafloor, is as tall as Japan’s Mount Fuji. And, as was announced in February 2024, the robotic sleuth found them to be decorated by a cornucopia of critters. Peach-hued corals seemed to wave hello in the shimmering water. Squid-like beasties flitted about as if drifting through a zero-gravity cosmos. Sponges with a glassy lustre danced in slow motion.

This may sound like a world beyond imagination, but none of this came as a surprise to the scientific team. Sure, they were delighted, remarking that this discovery far exceeded their expectations. But they weren’t shocked because the deep sea is almost always bursting with biology. You’d have to go out of your way to find corners of the seafloor that aren’t oozing with some sort of life.

Undersea volcanoes have been known to be citadels of life for several decades. Marine life appears to consider them prime real estate. Some use these mountains as permanent abodes, places to feast and breed, sleep and nurse their young. Others see them as Stygian waystations—rest stops on long journeys across the sea.

Extinct volcanoes are comfortable environments for many types of life, but even erupting ones are swarming with animals capable of withstanding high temperatures and pressures, and even the oft-acidic outbursts of active hydrothermal vents. Some animals use those natural exhaust ports as food traps: unwitting fish swim into them, get parboiled, and sink, ready to be snacked upon. And in 2023, for the very first time, scientists found life hiding even inside the rocks of these hellish chimneys—mostly worms, happily wriggling about in what most animals would regard as lethal conditions.

With that in mind, discovering a century’s worth of novel species in a matter of days is thrilling. But deep-sea discoveries become more profound when we contrast them with our myriad adventures into space.

There is probably life somewhere out there in the cosmos. And there’s a decent chance it could be hiding out, in some form or another, in liquid-water oceans hiding beneath the surface of a moon of Jupiter or Saturn—or even further afield. Perhaps we’ll find it someday, perhaps not. But for now, and for some time to come, whenever astronauts pass over that thin blue line that protects us from the frigid, hostile vacuum of space, they will not have the pleasure of seeing a world that teems just beyond our sight.

The opposite is true of the world’s submerged realms. “Normal” rarely denotes something exciting. That doesn’t apply when it comes to the oceans. Life—the sort previously unknown to science—is everywhere in the deep. Almost every single time scientists go looking for life in Earth’s oceans, they find something brand new. The planet’s waters are an embarrassment of alien-like zoological riches. And the unerring pervasiveness and diversity of life in this watery wilderness is so wonderfully normal that finding a hundred new species on an underwater volcano is also, somehow, nothing out of the ordinary.

Wildlife often turns up in the news because it’s in trouble, on the fast-track to extinction. But despite our perverse capacity for environmental destruction, there are corners of the world where life is getting on with it. It must be noted that several of the ecosystems found on the seamounts are potentially or actively vulnerable to ocean warming and acidification, and the rise of deep-sea mining. That is sad to know, but it is good to be aware of them, for future protection efforts. For the moment, these aquatic arcadias are overflowing with zoology—a mote of hope that we can all welcome in challenging times.

Robin George Andrews is a doctor of volcanoes, an award-winning freelance science journalist, and the author of two books: Super Volcanoes: What They Reveal About Earth and the Worlds Beyond (2021), and the upcoming How to Kill an Asteroid: The Absurd True Story of the Scientists Defending the Planet (2024).

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook