The Vermont Town That Has Way Too Many Organs

After decades of organ donation, Brattleboro is looking for new homes for old musical instruments.

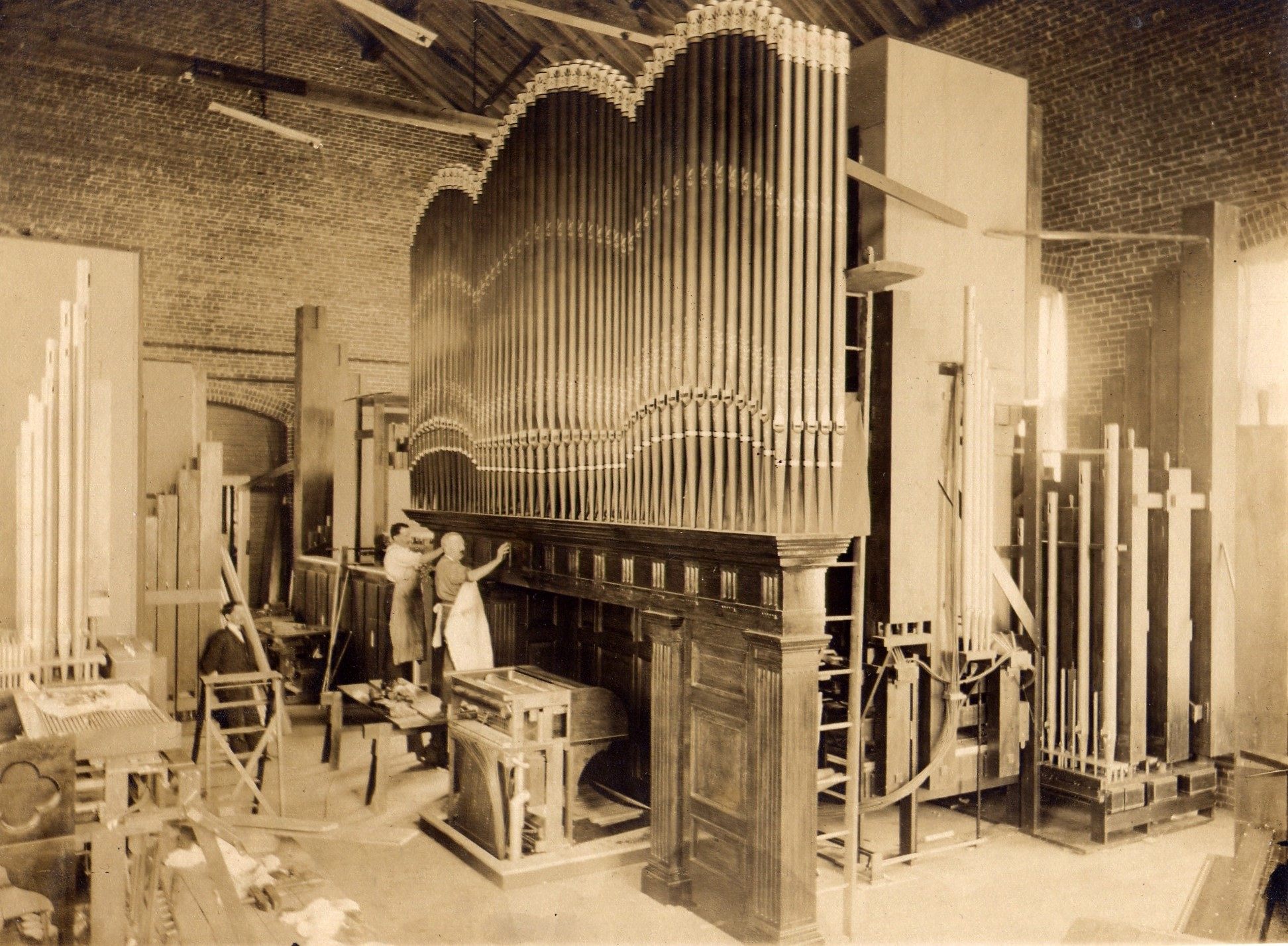

In its heyday, the Estey Organ Company factory was the beating, bleating heart of Brattleboro, Vermont. It produced more than half a million organs in total and, at its peak, employed more than 500 people. On a fateful day in 1960, however, the assembly lines shut down and workers departed. After nearly a century in operation, the organ factory had gone silent.

And then, like the most improbable boomerangs, the organs started coming back.

Families with old, unwanted Estey organs started to donate them, one by one, to the Brattleboro Historical Society. First a few, then a few more, and the organs kept coming. Over the years, hundreds of organs have made their way back home. At first, the historical society was at a loss for what to do with them all.

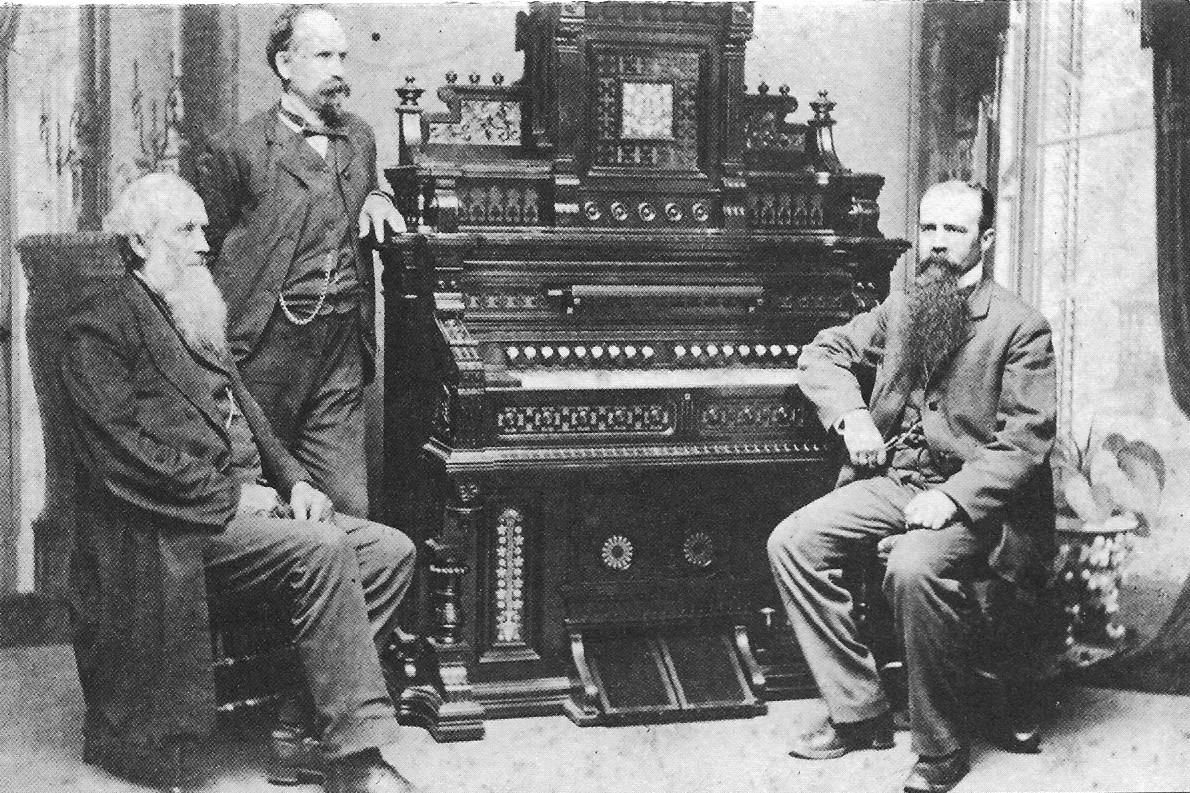

In 2002, the society chose the most interesting and playable organs and opened the Estey Organ Museum on the premises of the old factory. A once-booming coal-fired engine room became a showcase for the great variety of organs that were manufactured in the surrounding buildings: the ornate, carved Pompadour, the mother of pearl–keyed Melodeon, a deconstructed pipe organ that you can walk inside, and many others.

Beyond the museum, since the 1970s, the Brattleboro Historical Society amassed what might be the largest organ collection in the world, at around 200 instruments. The majority are stored in other adjacent factory buildings owned by Barbara George, a historic preservationist and longtime Brattleboro resident.

“In a way, it’s my fault that we have all these organs,” says George. She was generous with the old factory space, which at first provided ample room. But after years of accepting any and all organ donations, many of the buildings began to fill up. It was a unique predicament for any local society. What do you do with hundreds of antique, mostly unplayable organs?

Twenty-four of the factory’s original 29 buildings still stand, recognizable by their blue-gray slate shingles, installed in 1870 to prevent fires. Inside them, piles of sawdust speak to a family of raccoons that might take up residence in the winter. But even a thick layer of dust can not hide the elegance or craftsmanship of the instruments—carved wood, mirrors, elaborate bracketry. Some of the organs are arranged neatly in rows. The children’s organs are stacked on shelves. In some rooms, heavy organs are strewn about, creating mazes.

“They’re a curse,” George says, only half-joking. Today, the museum only accepts donated organs in perfect working condition, or rare or unusual examples. But this hasn’t completely stopped the tide. On a couple of occasions, organs have been anonymously left outside the door of the museum. “In the museum world, we call that a ‘drive-by donation,’” says George. The museum received between five and 30 organs a year when it was still accepting them.

When an organ does arrive at the museum it gets cataloged and assigned a unique number. In the labyrinth of organs on the second floor of one of the factory buildings, George points out an instrument with a tag that reads, “2004.024.” The 24th organ of 2004.

Estey’s flagship product was the reed organ, a musical chimera with the air power of an accordion, the metal reeds of a harmonica, and the keys of a piano. A foot-powered pump pushes air through reeds, resulting in resounding notes that are determined by the fingers on the keyboard. Reed organs reached the height of their popularity in the early 1900s. Cheaper than pianos and easier to maintain, they became a staple of the middle-class family parlor. The Estey Organ Company was one of the largest producers in the world.

They came in an astonishing range of shapes, sizes, and uses, from children’s toys, to living-room centerpieces, to the crown jewels of community churches and theaters. Some of the organs were designed to fold up into little suitcases and could be taken anywhere. The historical society has photos of chaplains playing portable Estey reed organs in World War II, and the society boasts that their organs have pumped out tunes on six of the world’s continents (poor Antarctica). “The Estey Organ Company provided hundreds and hundreds of jobs and put Brattleboro on the map,” says Dennis Waring, ethnomusicologist and author of the book, Manufacturing the Muse: Estey Organs and Consumer Culture in Victorian America. “This was one of the more important enterprises in American music history.”

Rock ‘n’ roll and the rise of electric instruments, however, did the old organs in. “The sound of the reed organ is pretty snoozy … lugubrious. It’s not a lively instrument,” Waring adds. “The reed organ was becoming outmoded with other kinds of upbeat sounds.” However, the instrument is still occasionally found in contemporary music—John Lennon and Nico were fans.

Collecting so many of them, in one place, was never George’s plan. “The mission of the museum is to promote continued use and enjoyment. They’re certainly not doing anyone any good in here,” she says, referring to the dozens of organs in yet another factory room. As she walks around, she occasionally presses down on a foot pedal, which generates a wheezing sound and suggests hope for that particular organ. “If they play, we want to find new homes for them.”

That applies to the ones that don’t play anymore, too. George and others have organized “re-homing” events, where members of the public can visit a part of the old factory and adopt an organ. George hopes that some of the non-playable ones can be fixed by amateur engineers or people who like tinkering—or repurposed into something else entirely. “They make wonderful furniture,” she says, suggesting that old organ parts may provide the basis for a creative bookshelf or bar. She points to a pile of ornate organ parts and pipes, which are arranged in a neat row, sorted by size. “Someone could make something out of this stuff.”

Estey may have the most inventory, but isn’t the only defunct organ factory in New England. The famous Sterling Organ Company factory was located in Derby, Connecticut. The Derby Historical Society’s website explicitly states that it does not accept donations. John Carnahan, who manages the Estey Organ Museum’s email account, says that he receives at least one message a week from someone looking to donate an organ.

“People don’t want them,” says George, “but they also don’t want to throw them away.”

Brattleboro’s best bet for its tidal wave of busted organs is to raise awareness about just how many they have, so they can find people willing to breathe new life into them. Says George, “We’d most like to see a reed organ revival.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook