How Competitive Walking Captivated Georgian Britain

In 1815, thousands of people came to watch George Wilson, the “Blackheath Pedestrian,” walk 1,000 miles.

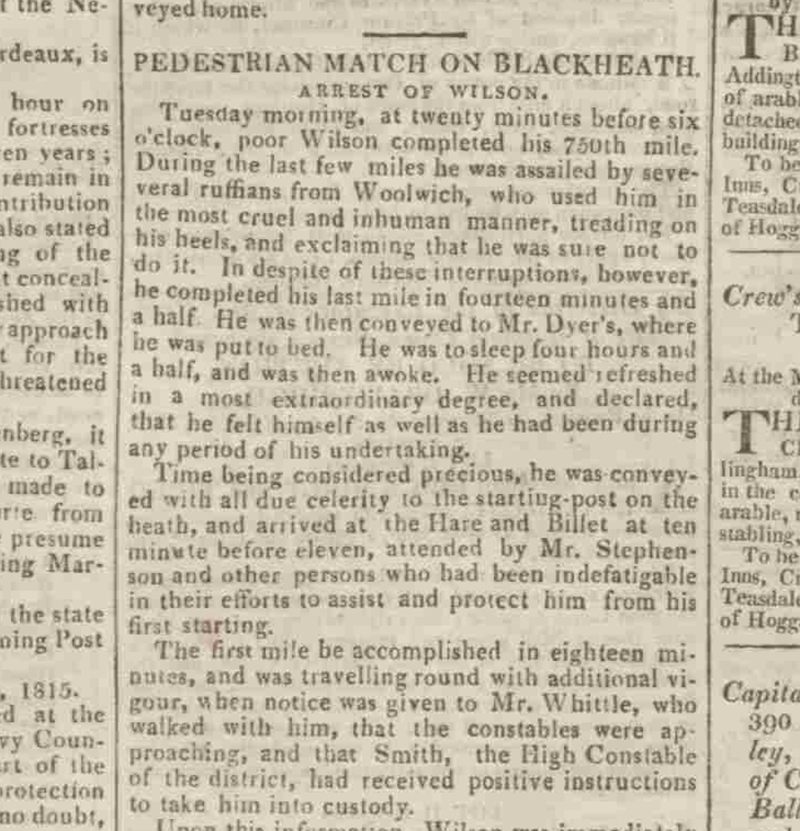

On the morning of September 26, 1815, George Wilson was arrested. For walking.

“It never reached my apprehension, however, until chastised by your all-powerful authority that walking alone on the skirt of a wild heath, remote from the ordinary intercourse of the busy throng, was a violation of public morals or a breach of the peace,” Wilson griped in his memoir.

Except, that’s not exactly what happened.

Just over two weeks earlier, on September 11, 1815, 50-year-old Wilson had taken his first steps on a 1,000-mile walk, one of several feats of long-distance walking called “pedestrianism” that enthralled Britain in the early 19th century. He walked on a pre-measured circuit around Blackheath common, an area of public grasslands outside of Greenwich, for a sum of £100.

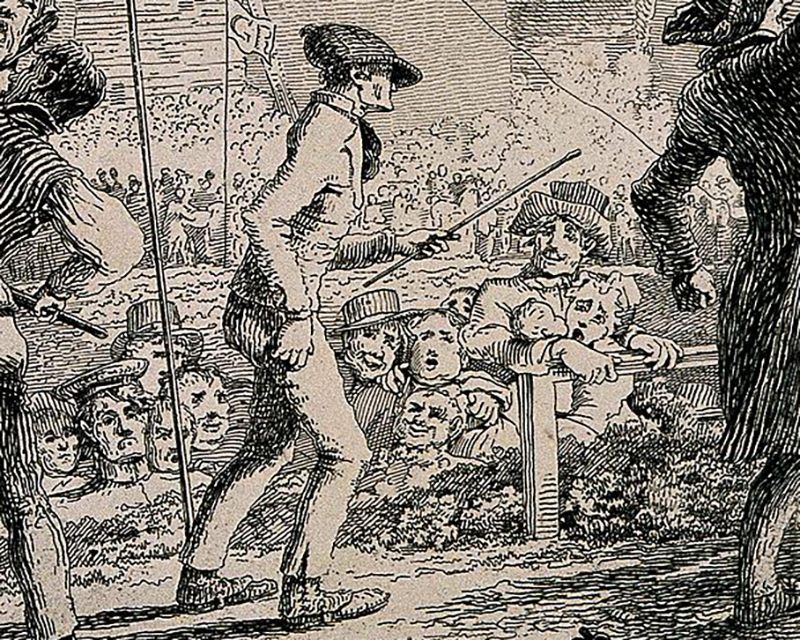

The crowds of people who’d come to watch the “Blackheath Pedestrian,” as the press called him, were lively but manageable. However, as Wilson tramped on, the number of spectators grew. By the day of his arrest, he’d walked an astounding 751.25 miles around Blackheath while, according to a contemporary report, the crowds had grown to “thousands and tens of thousands of idle and disorderly persons.”

“So many mouths required an adequate provision of beer and spirits; booths were erected and the Heath wore the appearance of an extensive fair,” wrote a lawyer who analyzed Wilson’s arrest in the months after. The Heath was alive with acrobats and “rope-walkers,” fire-eaters and ballad singers, dog fights and pony races. “Brothels were brought in from London to the spot, and drunkenness and debauchery were rife upon every part of Blackheath,” the lawyer continued. “At night, the neighborhood was assailed by the shouts of intoxication, and the families in the vicinity disturbed by every species of riot and confusion.”

Bookmakers were doing a brisk business in bets, but after seeing Wilson easily put down 50 miles a day and more, those who had bet against him now tried to stop him. Though Wilson was himself “quiet, inoffensive, and unassuming,” and only 5-foot-4 and 121 pounds, he had protectors armed with 10-foot staves, bludgeons, and in one case, a bayonet, sweeping the path in front of him. Local authorities were understandably nervous: The riotous carnival atmosphere was ripe for insurrection and violence.

So when Wilson was arrested and charged with disturbing the peace, it wasn’t without reason. The magistrates were right in thinking that if Wilson were stopped long enough, the crowds would disperse. During his hearing on October 5, Wilson was acquitted of the charges, and although he’d by then lost the challenge, he hadn’t lost the affection of the nation. A two-pence ballad entitled “The Quizzical Quorum or the Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Black Beaks of Blackheath” made it clear what everyone thought of the magistrates’ “comical warrant,” and even better, the London Stock Exchange allegedly took up a collection of £100 for him.

Wilson was famous the country over for his endurance, but exactly why watching a man walk around in circles for weeks on end was so exciting is down to three peculiarities of late Georgian culture: the growing love of sporting spectacle and sport as entertainment, the deep and abiding affection for gambling, and the prominence of pubs.

Pedestrian matches, along with boxing and horse racing, emerged at the very beginning of leisure culture, when the Industrial Revolution had begun to mean that more people had more free time and more free money. These matches prefigured the later sport-as-entertainment model: They were among the first organized sporting events for the masses, relying on both the athleticism of the participants and the pageantry of the event itself, offering a respite from the grim realities of working down a mine, in service, in trade, or on a farm. “It was just something different in their lives, because life at the time was harsh, certainly for the working classes,” says Archie Jenkins, a former physical education teacher and now sports historian.

Pedestrianism also had an advantage over other sports: There were few barriers to participating. All a contender needed was the ability and will to walk, and working people did that all the time. “Everybody had to walk, unless you were one of the 10 percent who had a horse,” says Derek Martin, a retired lawyer and sports historian who has researched the history of pedestrianism. Spectators therefore already had a built-in understanding of the sport. “You appreciated a good walker.”

Couple that with the fascination of watching someone do something that seemed physically challenging to the point of impossibility, and pedestrianism was a hit. “It’s the fun in watching people kill themselves slowly in front of you, to some extent. Or like Formula 1 racing, secretly you want to see a crash,” says Martin.

This fascination was certainly present from the beginnings of popular pedestrianism, which started with the exploits of Captain Robert Barclay Allardice. Barclay, a 29-year-old Cambridge-educated Scottish gentleman and son of a Member of Parliament, walked 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours in 1809 on Newmarket Heath near Cambridge. When he limped over the finish line on July 12, he had earned his enormous pay-off.

Barclay’s initial wager was £1,000, a mind-boggling sum considering that the average farm worker earned just £50 a year. As Professor Peter Radford writes in his book The Celebrated Captain Barclay, side-bets pushed Barclay’s take up to £16,000, roughly 320 years of income for most of the people cheering for him. The total amount of bets made by spectators on Barclay’s walk, The Times reported at the time, came to £100,000, or about £7.5 million in today’s money.

Britons loved, and still love today, gambling. “They would gamble on anything—if it moved, they would gamble on it,” says Jenkins, explaining that there were virtually no laws restricting gambling. “We used to gamble on people running backwards, how many stones they could pick up in an hour over a set distance. [Pedestrianism is] something to gamble on.”

That fact was not lost on anyone, particularly publicans. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, pubs actively organized pedestrian matches. They would put up the competitors, advertise, take bets, offer spectators a place to discuss the bouts over a pint, and then sit back and reap the profits. “The publicans became the entrepreneurs, they saw a way of making money getting people into the pubs, with gambling as well,” Jenkins says.

The Blackheath Pedestrian’s aborted attempt to walk 1,000 miles in 20 days was by no means his only feat of long-distance walking. Wilson, son of a bankrupt shipbuilder father and pawnbroking mother, was a working man, whether that meant peddling books and pamphlets door-to-door or tax collecting in the villages around his native Newcastle. But by 1814, Wilson was penniless and in debtors’ prison. Desperate, he took bets from his fellow prisoners: He claimed he could walk 50 miles in 12 hours. After measuring up the prison yard (33 feet by 25-and-a-half feet) Wilson made 2,575 circuits, finishing the full 50 miles with four minutes and 43 seconds to spare. He won £3 and 1 shilling.

After he was released, Wilson turned to walking for money full time, making him one of the first professional sportsmen, but soon found that Barclay’s windfall was the exception, not the rule. There wasn’t a lot of money in professional walking. To supplement his income, Wilson sold picture postcards of himself in his walking kit (his green silk cap and pantaloons), made public appearances on stages across the country, and wrote his memoirs.

In 1822, he decided to end his career on a spectacular note: walking 90 miles in 24 hours. On Easter Monday, before a rowdy, ballooning crowd of 40,000 people at the Town Moor racecourse in Newcastle, he did it with 14 minutes to spare. A day that could have ended in triumph, however, was plunged into disappointment when Wilson’s appeal to the crowd for donations in appreciation of his magnificent endurance yielded a pittance. He walked away in disgust.

Wilson died on the 11th of April 1839, in Newcastle, at the age of 73. By this time, the popular passion for pedestrian events was waning. “I suspect that was because the financial situation of the country got worse and people were more concerned with making a living and keeping their head down,” says Martin. “After that, people weren’t prepared to go and give money to walkers.”

There was another reason, too: Newly-minted Victorian morality was starting to disapprove. Over the next 30 years, pedestrianism took on new dimensions as a sport, encompassing running and sprint races, but to many Victorians, it remained too working class, too mired in gambling and boozing, and, when it came to the long-distance feats, too easy to fake or cheat.

Middle and upper class athletes, often Oxford and Cambridge grads who wanted to raise the sport out of the muddy morass of the pub-cum-betting house, began forming athletics clubs. Initial membership was restricted to only other middle and upper-class sportsmen and explicitly not artisans, labourers, or “mechanicals.” These more structured clubs nevertheless flourished, giving rise to running, football, rugby, and cricket clubs. By the end of the century, football took the place of pedestrianism in the hearts of working class sport fans and several former pedestrians found new vocations as trainers of new football clubs.

Today, pedestrianism of the kind that Wilson and Barclay might recognize still exists in racewalking, an Olympic sport. But it can’t command nearly the crowds that they did. And it’s got a bit of a reputation for, well, looking silly. In 2012, long-time sports commentator Bob Costas told American Way magazine, “Look, I know that they are athletes…. But it looks so funny. You know what it really looks like? It looks like a person who has to go really bad. ‘I gotta go, gotta go, gotta go right now’—except they just don’t want to break into a full-scale sprint.”

Entertainment starved Georgians would almost certainly not agree.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook