In 1859, the United States and Britain Almost Went to War Over a Pig

Hundreds of soldiers and sailors faced off over one tiny island in the Pacific Northwest.

San Juan Island is, by any account, a small piece of land—19 miles long and seven miles wide—just off the coast of Washington state. Today farms spread over the island, and a ferry brings tourists ready to soak in the vibes of the Pacific Northwest. It’s not an obvious site for an international conflict between the United States and England. But in 1859, both countries were amassing troops here, ready to start a war over the rights of the farmers who had settled here. It is known today as the Pig War, but before any pigs were involved, there was a fight over sheep.

The Pig War began with a problem specific to the Age of Exploration: A number of different countries had sent men in boats to sail along the western coast of North America and map parts of the interior. Those countries all believed, by virtue of this act, that this large stretch of land now belonged to them. (The people who had been living in these lands before they were “discovered” by European powers were not considered in this political calculus.) In the early 19th century, Britain, the United States, Russia, and Spain all had designs and claims on what was called Oregon Territory, which stretched from what’s now the southernmost border of Alaska, down to California, and east to the Rocky Mountains.

Over time, the United States and Britain convinced Russia and Spain to back off their claims, and through the 1840s agreed to a joint occupation that left the issue unpressed for a spell. As white settlers began to arrive in greater numbers, though, this uncomfortable arrangement became a problem. In 1846 the Treaty of Oregon drew a line along the 49th parallel, cutting the territory into two and creating what’s now the U.S.-Canada border.

But at the edge of mainland, the border went down, according to the treaty, “to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver Island and thence southerly through the middle of the said channel.”

This is the flashpoint of the Pig War. Even when the treaty was signed, the negotiators knew there was a problem: There was more than one channel this line could describe. One, the Rosario Strait, was closer to the mainland and granted San Juan Island to the British. The other, the Haro Strait, was farther west and gave San Juan Island to the United States. It’s easy to guess which country favored which interpretation. For the next few years, this ambiguity remained an abstract problem—until settlers started edging closer to the contested island, at which point a British official sent in the sheep.

James Douglas had risen through the ranks of Britain’s colonial hierarchy to become governor of British Columbia, and he was determined that San Juan Island would remain a British possession. British-held Vancouver Island, valued for its climate, water power, coal, and fisheries, lies just across the Haro Strait from San Juan Island, and controlling both would mean control of access into the Strait of Saint George, and the city of Vancouver. But the political and strategic implications went further. Both sides, writes historian Scott Kaufman in his book, The Pig War: The United States, Britain, and the Balance of Power in the Pacific Northwest, 1846-1872, “believed that whichever country possessed the island would have the upper hand in the balance of power in the Pacific Northwest, with enormous implications for both countries’ regional economic and military interests.”

At first, Douglas tried to convince the people of British Columbia to settle San Juan Island, but, Kaufman writes, they were reluctant to leave the town of Victoria for so isolated a place. Instead, at the end of 1853, Douglas had to be satisfied with having the Hudson Bay Company send sheep, more than 1,300 of them, along with one British man, Charles Griffin, to run the island’s newest farm with the help of native shepherds.

This influx did not escape the notice of American officials, and the local collector of customs, Isaac Ebey, decided that Hudson Bay Company, a de facto arm of the British government, should pay taxes on the sheep. He sailed to San Juan Island to present Griffin with a bill and, when it went unpaid, deputized a tax collector, Henry Webber, to oversee the island. When Webber arrived, he set up his camp directly behind Griffin’s cabin and raised an American flag.

That did not sit well with Griffin, who deputized one of the shepherds, Thomas Holland, to arrest Webber. When the newly appointed constable tried to serve the warrant, though, Webber pulled a gun and leveled it at shepherd’s chest. This was the first threat of violence in the conflict, but neither side pressed the issue. Griffin had Holland back down, and Ebey ordered Webber to stay on the island and keep track of the taxes Griffin owed without trying to collect them. For a few months, things were quiet.

Later that year, though, another American official, the commissioner of newly formed Whatcom County, William Cullen, took an interest in the sheep. Like Ebey, Cullen believed San Juan to be an American island and decided Griffin owed taxes. Four times, the county sheriff demanded $80.33 in back taxes from the sheep farm, as Mike Vouri writes in The Pig War: Standoff at Griffin Bay, and in March of 1855, when Griffin once again refused to pay, the sheriff brought a group of Americans to the island for a tax sale. They rounded up a portion of the sheep, auctioned them off, and got 34 of them into boats before Griffin and his herders knew what was happening. Griffin called in reinforcements, and a British ship pursued the Americans, in their sheep-filled boats, through the contested waters before giving up the chase.

For the next few years, tensions on the island stayed low, as Griffin oversaw the growth of the farm to close to 4,500 sheep, along with pigs and other animals. But in 1859 American settlers started arriving, intent on setting up their own farms. One brought 20 cattle. These newcomers did not take much stock in Griffin’s presence there. One new farm was located smack in the middle of one of Griffin’s best sheep runs.

Despite their best efforts, the humans on the island had managed to avoid direct conflict, but the animals were less discreet. In summer 1859, one of the pigs from Griffin’s farm discovered a plot of tempting tubers on the farm of American Lyman Cutlar and availed himself of the delights. Cutlar, having fended off this same pig before, could not stand for this theft. He shot the pig.

That unceremonious execution quickly escalated. Griffin wanted payment for the dead pig but dismissed Cutlar’s offer of $10. The price, he said, was $100, a bounty Cutlar was unwilling to pay. According to Cutlar’s account, Griffin then lost it, as Vouri recounts in his book. “It is no more than I expected,” Griffin allegedly told him. “You Americans are a nuisance on the island, and you have no business here. I shall write Mr. Douglas and have you removed.”

Cutlar, by his own estimation, stayed cool. “I came here to settle for shooting your hog,” he said, “not argue the right of Americans on the island, for I consider it American soil.”

To be fair to the poor deceased pig, Cutlar’s decision to fire was not the only source of tension on the island. When General William Harney, who commanded U.S. military forces in Oregon, visited the island, the settlers regaled him with many tales of woe. But the pig story stuck in Harney’s head. After hearing about the settlers’ tensions with the British and native tribes, Harney decided to dispatch a small unit of troops to protect the Americans there—and in his report to his superiors about this decision, the pig incident loomed large.

By the end of July, a unit of 66 American soldiers, led by Captain George Pickett, had settled on the island. The British couldn’t abide this, and two days later a British warship showed up off the coast. Douglas, the governor, urged the Navy to send still more ships and land troops on the island. By August 3, there were three ships off the coast. In a parlay with British naval officer in command, Captain Geoffrey Phipps Hornby, the American Pickett held fast to his position that if British troops attempted to land, he would have to stop them.

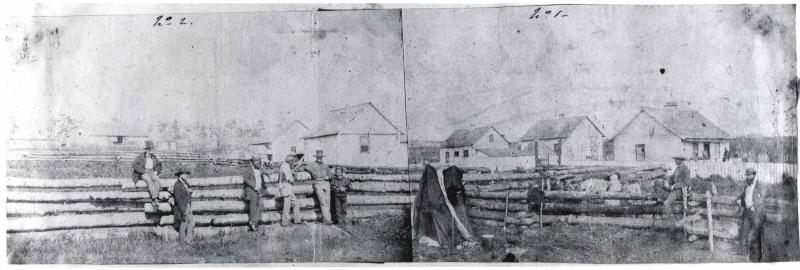

Once again the two sides had come to the brink and cooler heads prevailed. Hornby held back, but both sides built their forces over the next few weeks, until there were hundreds of American soldiers on San Juan, and more than 2,000 British sailors in ships. Meanwhile, the island’s settlements had grown to include more than one groggery, and shacks brought over from an abandoned camp in Bellingham Bay, where soldiers could find whisky and women. Civilians from Victoria also sailed to the island to watch the conflict unfold.

When leaders on both sides heard about what was happening, they immediately decided to to de-escalate the conflict. By the fall, both sides had agreed to draw down their forces, until there was just one company of American soldiers on the island and one British ship off the coast. In March, the two countries agreed to jointly occupy the island, with an American camp on one end and a British camp on the other.

This was the situation for the next 12 years. In 1871, a few years after William Gladstone became Prime Minister of England, the countries agreed to decide their remaining land disputes through arbitration. Both made their cases before a commission appointed by Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm I. The next year, the conflict was finally resolved. The border would go through Haro Strait, and San Juan Island would be American. In the end, the only life that was lost was that of the hungry pig that gave the war its name.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook