Utah’s First Federal Surveyor Fled the Territory Fearing for His Life

And helped start a war between James Buchanan and Brigham Young.

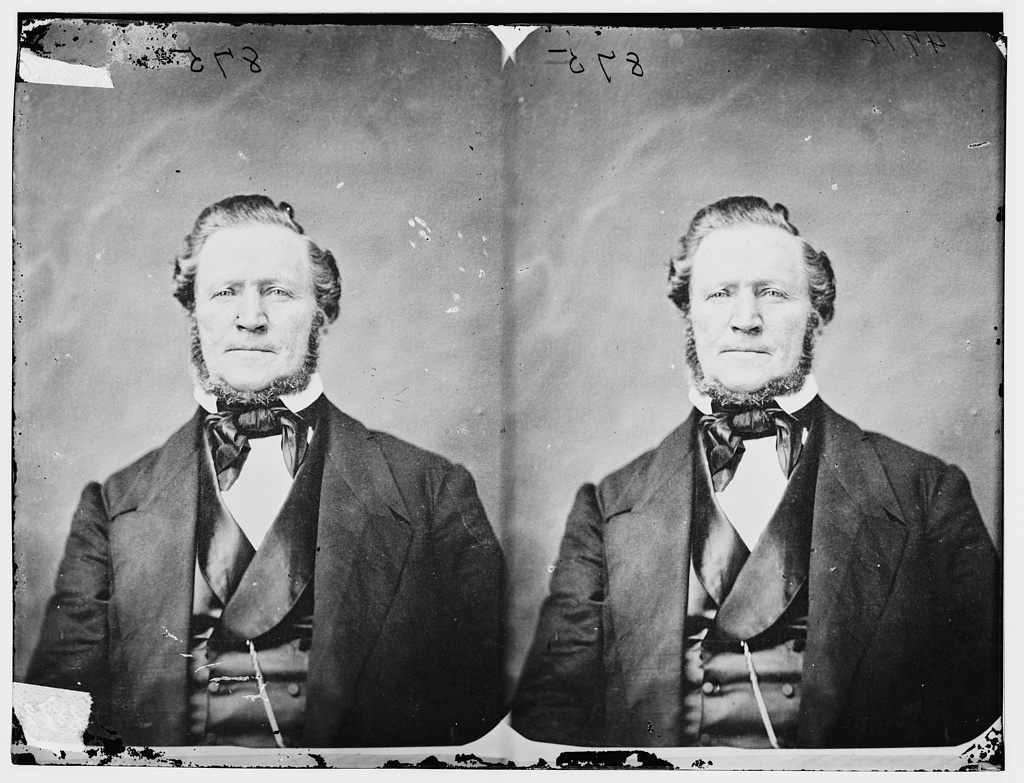

When David H. Burr, the first Surveyor General of Utah Territory, showed up in Salt Lake City in July 1855, Brigham Young, then territorial governor, was almost certain he was a spy for the federal government. “Burr has been watching for evil ever since he has been here,” Brigham Young wrote to Utah’s representative in Congress.

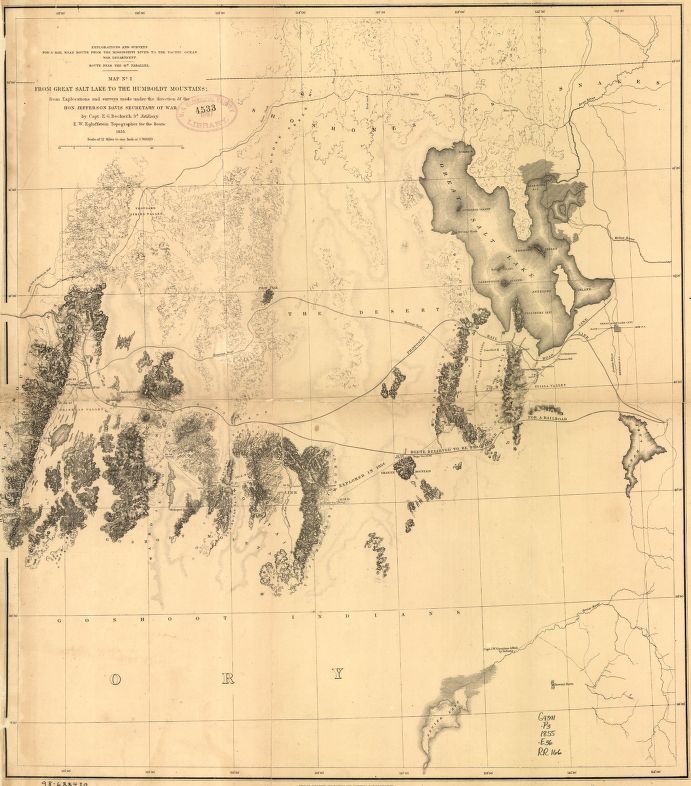

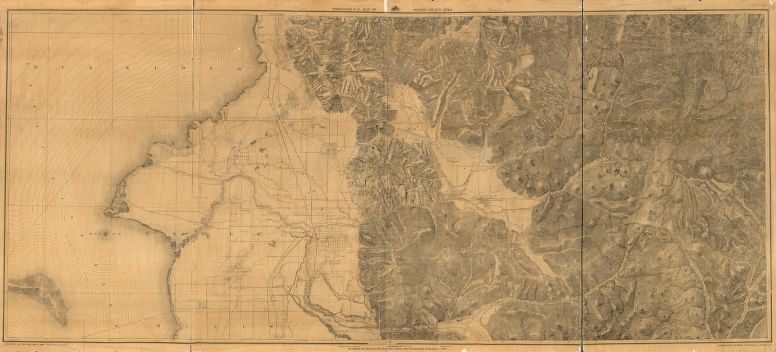

Young, also the spiritual leader of Utah’s Mormon settlers, did not have a high opinion of federal officers in general. He called them “dog and skunks … sent here by the authority of Government to rule over men as far above them as they are above the low and vicious animals they so faithfully represent.” But Burr posed a particular threat. He had made his name mapping states further east, but his task in Utah was a very different kind of job. He and his men were meant to parcel out the land of the territory into plots that could be sold or settled, and to the Mormon communities who already lived on some of the land, that work was a threat. Once the federal government had measured the ground beneath their feet, there was no guarantee they’d be allowed to stay.

In 1850s Utah, “no conflict created more distress than the battles over federal land surveys,” writes historian and professor emeritus at Brigham Young University, Thomas G. Alexander. For two years, Burr and his team were harassed, spied on, and accused of fraud. At the time, Burr was sending distressing reports back to Washington, warning President Buchanan that Utah’s Mormons were preparing for battle.

Just two years after they arrived, having surveyed 2.5 million acres—a small fraction of the territory—Burr and his team fled the territory in fear for their lives, and Buchanan sent in 2,500 troops to install a new governor.

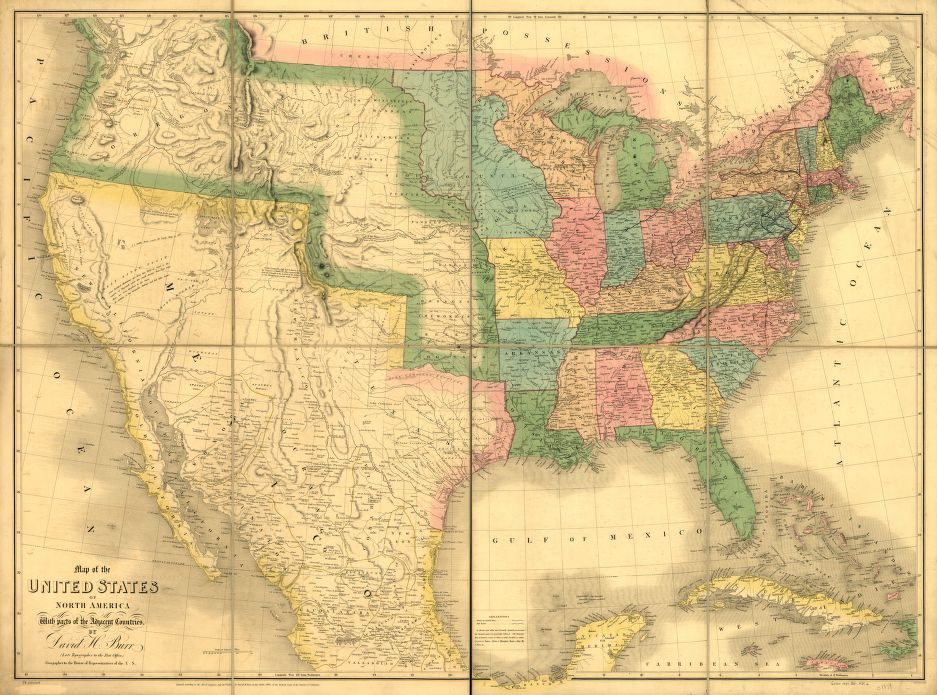

Mormon settlers had first come to Utah in 1847, after the church’s founder, Joseph Smith, was killed by a mob in Illinois. Smith’s followers had settled in Illinois after the governor of Missouri, their previous home, had ordered them “exterminated.” Young, the group’s new leader, decided to move west, to the isolation and freedom of the desert. Not long after the Mormons settled by the Great Salt Lake, though, the United States took possession of the area as spoils of the Mexican-American War, and the church’s followers were once again pushed into negotiations and clashes with unsympathetic and often prejudiced American politicians.

Even though some settlers had been living in the territory for close to a decade, they had little claim to the land they occupied. The federal government still recognized, to some extent, the land claims of local tribes, but ultimately considered itself the owner of all land in Utah. Although the Utah legislature had created land-use laws and authorized county surveys, settlers were still living outside of any framework that would allow them to make legal land claims, so the Surveyor General’s work was a source of great anxiety to them.

Young and his allies weren’t wrong to be suspicious of Burr, even if they did use underhanded strategies to confirm their worries. They intercepted Burr’s mail, and found that he was sending complaints to Washington. Salt Lake City, he communicated, was larger than a town it was allowed to be under federal law. Burr also worried about the power and influence of the Mormon church. The territory gave control of scarce resources—such as the timber that grows only in canyons—to prominent Mormon leaders, who were supposed to manage them for the public good. Also, about a third of the church’s members had to give what legal rights they could claim to their land to Young and the church, an arrangement that Burr saw as a dangerous merger of church and state.

After reading Burr’s mail, a group of territorial officials, including the acting attorney general and the territorial marshal, confronted him. He needed to stop writing these letters, they told him, and “they would always know if he did so again,” according to Alexander, the historian.

At the same time, Mormon leaders were waging their own epistolary campaign against Burr. The Surveyor-General, according to Young, “was never anything else than a snarling puppy, snapping and biting at everything that comes in his way .... swindling the Government extensively, all the surveying that has been done by his party is not worth a groat.” Though they were supposed to be marking the survey lines with permanent monuments, Young wrote, “they stick down little stakes that the wind could almost blow over … . Not a vestige of all they do will be left to mark where they have been in five years.”

If Burr and his team weren’t doing their best work, it may have been in part because of the obstruction they faced from settlers. One surveyor, Charles Mogo, had his oxen stolen, and had to go out on one job with a team of guards. They received reports that Mormons were trying to turn native tribes against them by saying that they were coming to take away the land—which was not inaccurate, even if it was not the stated purpose of the survey. In some cases, according to Burr, hostile Mormons simply removed the markers his team had set down.

Soon these tensions escalated into violence. Another of Burr’s surveyors, Joseph Troskowlawski, was beaten almost to paralysis. Sunday sermons started to mention Burr and his men by name and inveigh against them. Burr soon left and federal troops came in. The resulting conflict, the Utah War, was not exactly a show of strength by Buchanan’s government. After a two-year standoff with Young and his people, negotiations ended the conflict and brought in a new territorial government. It was a black eye for the president, who was accused of acting in haste and ignorance, or of failing to sufficiently supply the troops he had sent.

The staff Burr left behind did not fare well either. Mogo was accused of stealing horses and was almost stoned to death by a Mormon mob. He fled—without his pregnant wife. (Their newborn son would later die on a cold and snowy journey to join him.) An office clerk, C.G. Landon, was beaten with rocks and clubs but managed to escape. A mob found him two days later at home, in bed, nursing his wounds, and he had to jump out of a second-floor window to escape. He headed, barefoot, out of Salt Lake City and disappeared. For months no one heard from him, and he was presumed dead before he finally showed up months later in Placerville, California, hundreds of miles away.

Back in Washington, Burr tried to explain himself and even asked to return to his post after the war. But the General Land Office fired him and had his replacement, Samuel C. Stambaugh, investigate the accusations of shoddy surveying. In his report, Stambaugh was not kind. He found Burr guilty of “great remissness … in not providing proper checks upon his deputies,” and the surveys themselves faulty. All the work had to be done over. Although tensions had dissipated somewhat, the new surveyor was not much friendlier to Mormon interests than Burr had been. He recommended the federal government not sell any land until Congress could “induce other than Mormon emigration to the Territory.”

It would be another nine years before the federal government opened a land office to facilitate sale of land to settlers, well after neighboring territories. Utah didn’t then become a state until 1896, again, years after the Dakotas, Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. Even then the federal government remained suspicious of the state’s Mormon population: Utah was let into the union only on the condition that the church’s official support of polygamy be abolished.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook