The Queer History of a 1937 Guide to London’s Public Loos

The slim volume on city toilets directed in-the-know readers to discreet hookup spots.

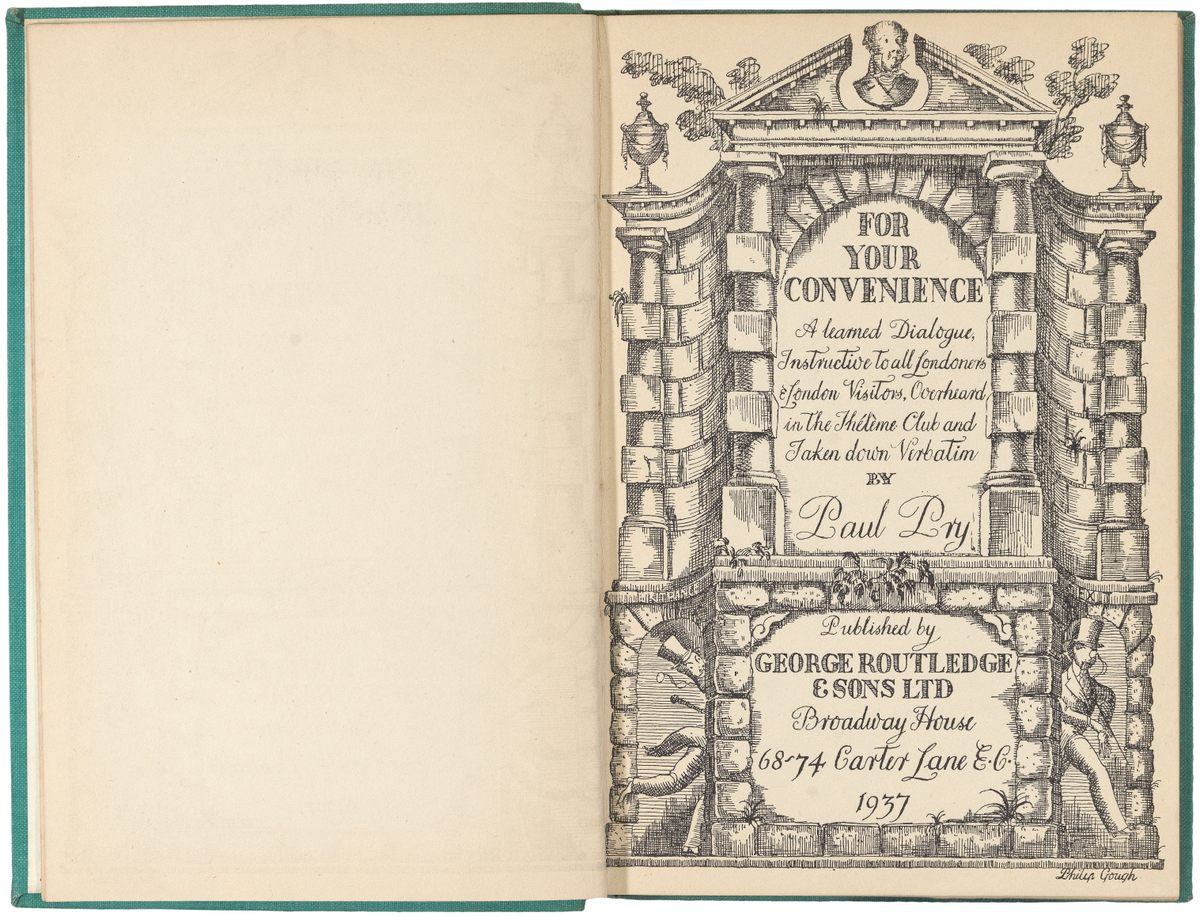

When you’re dashing around a city and nature calls, a public restroom is a godsend. (Some are especially heavenly, like the luxurious commode in New York City’s Bryant Park, where the sounds of flushing toilets mingle with a classical soundtrack.) If you needed to pee in London in 1937, you might have reached for a printed guide, bound in green cloth and sandwiched between two boards. The guide, titled For Your Convenience and written by Paul Pry (the pseudonym of the writer Thomas Burke), is organized as a chat between two men with full bladders, discussing places to relieve themselves while “walking through Wigmore street after three cups of tea.”

For those who knew what to look for, however, the guide wasn’t just telling people where to flush in a hurry—it was pointing men who wanted to be intimate with other men to places where it would be safe for them to do so. “It is, for all intents and purposes, an early guide to cruising in the capital,” writes Charlotte Charteris in Queer Cultures of 1930s Prose: Language, Identity, and Performance in Interwar Britain. A copy recently sold through Daniel Crouch Rare Books.

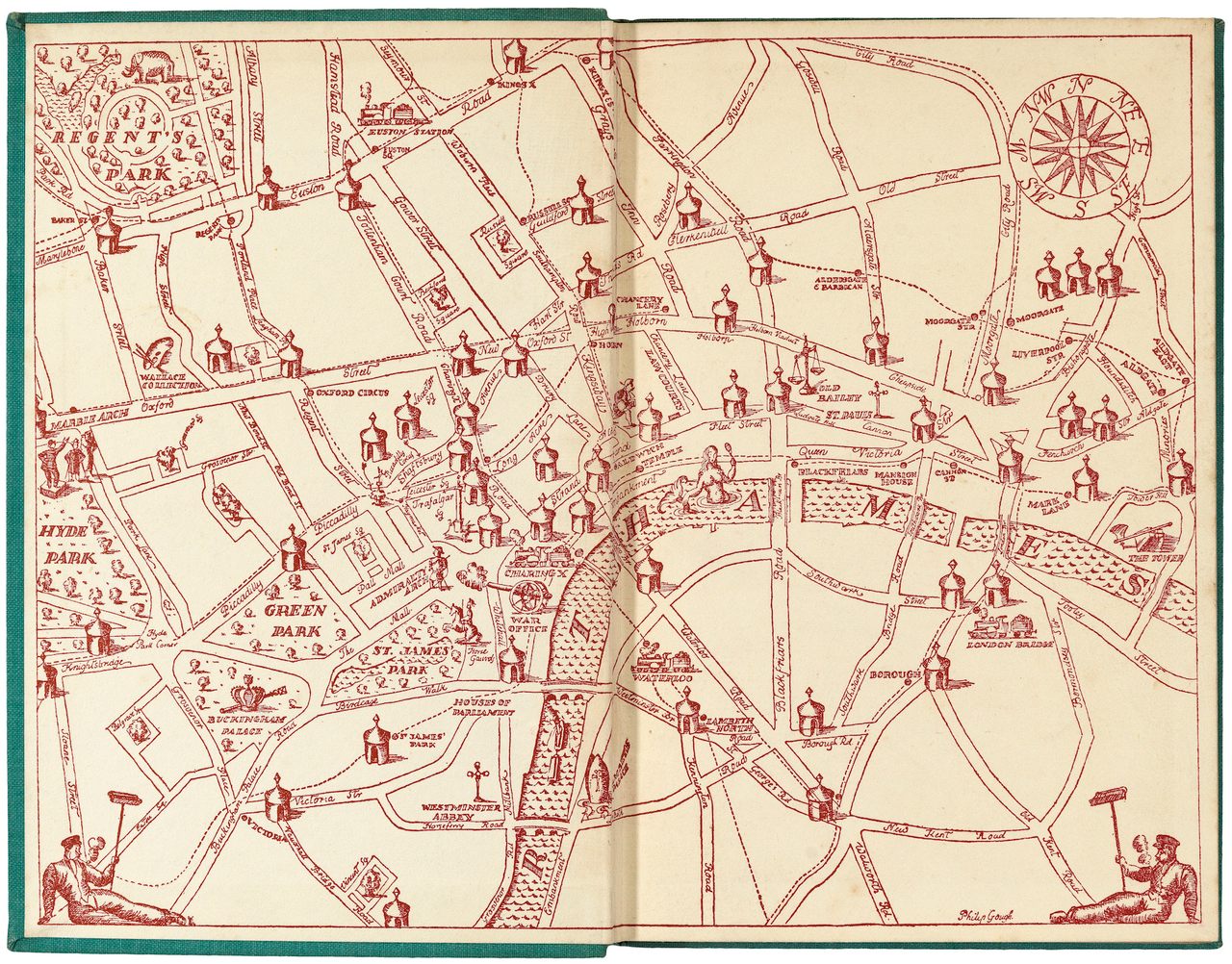

In Pry’s slim volume, an older man supplies a younger man with drink after drink in exchange for a share of his “extraordinarily precise knowledge of the city’s public toilets.” Finally, the younger man shares a map highlighting several dozen public bathrooms, also known as “cottages” and depicted as pavilions. (The illustrator was Philip Gough, who would go on to sketch scenes for editions of Jane Austen’s Emma and Lewis Carroll’s The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland.) The map in Pry’s book was much more than a narrative device: It was a service to readers, disguised as part of a story.

In an era when sexual encounters between men were criminalized under British law, bathrooms were among the few places where discreet relationships could take place nonetheless. Queer sex wasn’t legalized until the Sexual Offenses Act of 1967—and that legislation only permitted same-sex encounters that took place in private, between men aged 21 or older. (The law didn’t recognize or restrict lesbian relationships.)

Still, privacy didn’t insulate men from scrutiny. Police routinely canvassed known and supposed hookup spots, and bathrooms were easy targets. Because restrooms were static and fixed, officers could revisit them often, and that’s precisely what they did: In 1927, nearly all of the arrests made by officers of the city’s E Division occurred in 15 urinals, including ones in York Place and Cecil Court. Because police officers so often kept the toilets in their sight, public loos were places where men risked punishment.

Officers were especially hawk-eyed in Central London, “the symbolic heart of imperial grandeur, mass consumption, and tourism,” writes Matt Houlbrook, a historian at the University of Birmingham, in Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957. The district was home to places like Buckingham Palace and the Houses of Parliament, and police surveillance suggested that queerness clashed with a particular strain of national identity organized around monarchy and a stiff upper lip. In Central London, Houlbrook writes, “the queer was a dangerous incursion onto the defining spaces of Britishness, his presence striking because he seemed so out of place.”

Scrutiny of public toilets was particularly sharp in 1937, Houlbrook adds, as the city prepared for the coronation of George VI and Elizabeth as king and queen. In the year that For Your Convenience was published, “there was a marked intensification in the surveillance of West End streets,” Houlbrook reports, “as officers attempted to cleanse London’s public face.”

The book’s queer content is conveyed through both illustration and innuendo. Gough drew muscular men reclining on the edges of the map, their sculpted thighs and biceps almost bursting through slim-fitting shirts and trousers. In their chat, the speakers discuss how “places of that kind which have no attendants afford excellent rendezvous to people who wish to meet out of doors and yet escape the eye of the Busy [Policeman],” but are vague about the details.

London still has a lot of public loos—and several old ones that are now enjoying a second life as swanky bars and cafes. But many of the men who once looked for companionship in restrooms are a little freer to be themselves in the light of day. In 2013, seventy-six years after Pry published his book, the Parliament of the United Kingdom legalized same-sex marriage in England and Wales. Many same-sex couples tied the knot in London the following year, when the law came into effect.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook