Can Redwoods Save the World?

Not by themselves, but the Archangel Ancient Tree Archive is out to show how they can help.

For a tree too big to wrap your arms around, the California coast redwood, Sequoia sempervirens, is surprisingly elusive. Their bases might be elephantine, but the upper reaches, they’re lofty, inscrutable. It’s this zone that I’m preparing to enter, a fog-shrouded crown on the northern California coast. A guide cinches me into a harness, and before I know it, I’m 140 feet up, then 150, 160. I stare at the tree’s dark, gnarled bark to quell the vertigo rising in my temples.

By the time I’m about 20 stories off the ground, the dot-sized people staring up at me are gone, replaced by intertwined branches and needles that close around me like a net. Clumps of sage-colored moss dangle and an inexplicable calm descends. Somewhere, my mind is scrambling like a squirrel, aware that I’m dangling 200 feet off the ground, but the tree’s unrelenting solidity—it’s been here since before the Magna Carta, after all—is having an effect. There’s a stillness up here that passes understanding.

I should have seen this coming. It’s just the way David Milarch described it. Milarch’s singular goal in life is to bring these primeval forests back from the brink, and he knows just how to win people to his cause. The best baptism is the experience. I see it in the faces of others after they return from a crown visit: blooming cheeks, starry eyes, deep sighs. They’ve gotten big tree religion.

Milarch is counting on this kind of conversion, and he approaches his life’s work with a religious zeal. He is the founder of a nonprofit called the Archangel Ancient Tree Archive, and he’s out to spread the gospel of California’s coast redwoods. Years of droughts and shifting temperatures have already driven these evergreen giants out of some coastal zones they once inhabited. The trees can live for as long as 2,000 to 3,000 years, but some scientists think, the way things are going, that they could disappear from California in a fraction of that time.

Milarch spends his days tracking down the heartiest coast redwood specimens he can find, cloning them in his own lab, and then planting them in carefully chosen plots where they can thrive, hopefully for millennia. One site is a new experimental bed in San Francisco’s Presidio, part of the U.S. National Park system. Milarch’s goal is both to strengthen the coast redwood gene pool with clones of the strongest individuals, and to store loads of climate-change-causing carbon—more than 1,000 tons per acre of redwoods, more than any other kind of forest in the world. It’s a complicated mission with a simple philosophy: Save the big trees, and they’ll save us. Reckoning with climate change will take much more than that, but Milarch’s singular devotion is at least a reflection of the kind of zeal we’ll need.

For millennia, California coast redwoods seemed like the last tree species that would need to be saved. They are endurance champions that survive through thousands of years of natural floods, droughts, tsunamis, fires, and wild temperature swings. They can thrive and recover from damage so long as they can count on rainwater and coastal fog banks that roll in every morning. And it is those critical water sources that are dissipating as temperatures rise. The damp conditions the trees like—mostly in pea-soupy pockets of California and Oregon—are rarer than they used to be. Coast redwoods now occupy less than 10 percent of their original range. Their loss will have ripples—economic, ecological, emotional—particularly in the vast amount of carbon they can store.

In places where coast redwoods remain, their silent grandeur is simply overwhelming. So it’s at least a little ironic that one of their greatest advocates is such a talker. If you strike up a conversation with Milarch, you’ll get his life story inside of 10 minutes—from his motorcycle gang days in Detroit to the revelation that set him on his current path, involving a near-death experience, angels, and a disembodied voice that dictated a plan he wrote down in the wee hours of the morning. When he woke up fully the next day, he says, “There was an eight-page outline on that legal pad. It was the outline for this project.”

The angel who tapped Milarch for this mission seems to have picked the right person—not only is he an able tree-vangelist, but he is a third-generation shade-tree grower. His sons Jake and Jared, both of whom work for Archangel, make up the fourth. So he knows all the secrets of getting balky arborial species to reach their potential by locating the healthiest specimens, clipping and propagating them, and then nurturing delicate new trees.

In the primeval forests of California’s northern coast, Milarch knows what he is looking for: redwoods that have proven their mettle by surviving for a millennium or more. Some of these aren’t the fully grown behemoths, but just stumps or “fairy rings,” the term for a circle of sprouts that are exact clones of a fallen parent tree, thriving on its decaying remnants. “Redwoods, just before they die, they know they’re dying,” Milarch says. “They self-clone. There are a dozen trees [sprouting] from the root system, so that when she passes, she lives on.”

Once Milarch and his team find the right tree—if it’s not a stump already—they zip up to the canopy in harnesses and harvest hundreds of pale green branch tips, each about the size of a fingertip. These are spirited carefully back to Archangel’s lab facility in Copemish, Michigan. Taking these cuttings at just the right time is critical, it turns out. “We stay away from collecting material when the tree is stressed out,” Jake Milarch explains. “It has to be at a certain point of hardening off.” Too green and it will wilt, too mature and it won’t root properly.

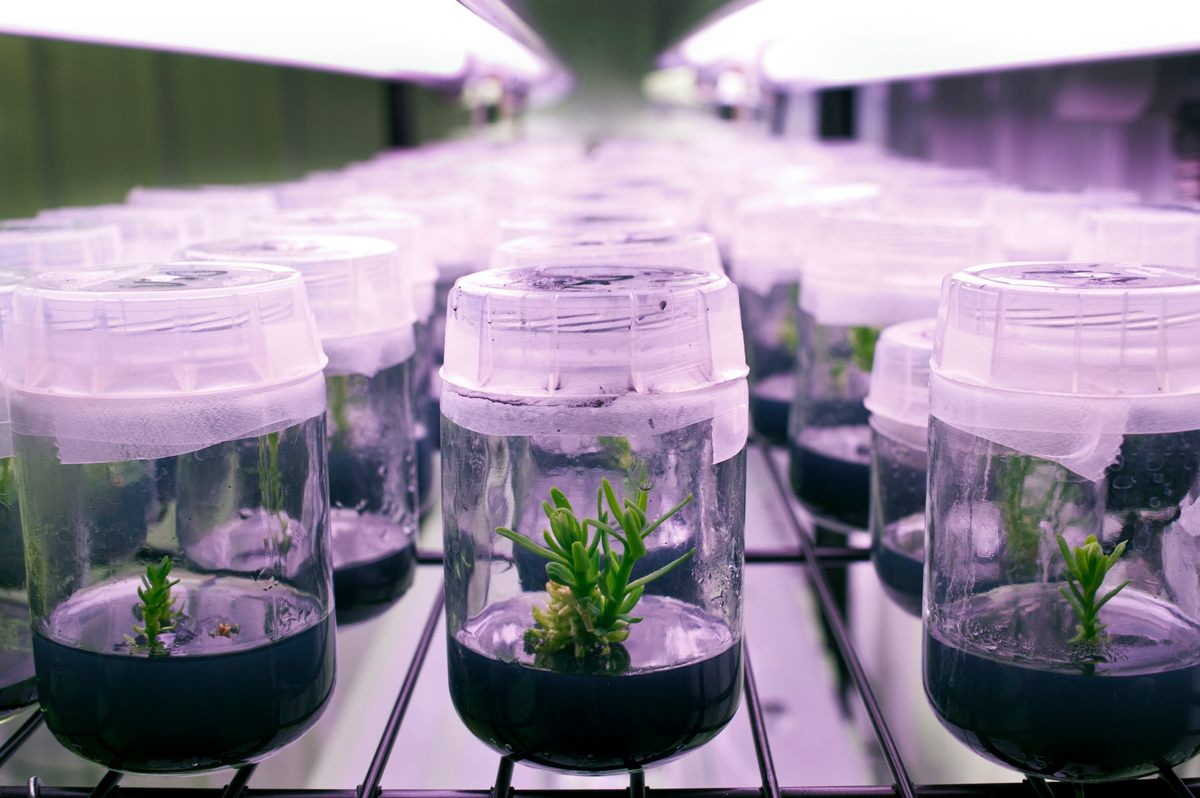

The next step is getting the cuttings to take root. Some thrive in rich soil with a dose of rooting medium, while others, Jake says, need more help—a process called micropropagation. “We’re taking tiny tips and basically multiplying them in vitro. Not down to the cell, but down to a stem the size of this—” he points to a dot on a spread-out map. These bits get nursed along in sterile vessels to prevent bacteria from interfering with a critical stage in development. But there’s still a lot of trial and error involved. Typically, only 3 to 4 percent of the tiniest coast redwood cuttings survive long enough to make it into the ground.

Deep in San Francisco’s Presidio, which sprawls under the southern approach to the Golden Gate Bridge, behind a chain-link fence, there is a sun-dappled clearing where dozens of wooden stakes are lined up in neat rows. Tethered to each is a spindly little Charlie Brown tree about a foot tall. When Presidio foresters wanted to plant an open area with coast redwoods and heard about Milarch’s cloning project, they reached out to him for healthy tree starts.

When Presidio staff planted these 75 cloned redwoods in late 2018, the National Parks Conservancy issued a press release—but it’s not a tourist draw, not yet. “It’s kind of tucked away,” says Presidio head forester Blake Troxel. “No one comes up here except us and the coyotes.”

The grove features a backdrop of gnarled old shade trees, including a few coast redwoods the park’s one-time military management planted back in the 1800s, each now more than a hundred feet tall. The smaller trees, all reared in Milarch’s Michigan lab, came from coast redwood stumps that predate the Roman Empire. The silver-gray fog bank that rolls over the site in the wee hours just about every night makes this ideal coast redwood territory, despite being more or less in the middle of a city. Even so, Troxel says, the new trees’ success in the grove isn’t guaranteed. The Presidio team tends the site aggressively to make sure the redwood starts aren’t eclipsed by faster-growing competitors. “The grasses are what make it difficult,” Troxel says. “We come through and brush-cut.” The baby redwoods also get drip irrigation a couple hours a week when it’s not raining, as well as infusions of compost from elsewhere in the park. To help the clones feel more at home, eventually, Troxel and his team will plant understory species that appear in natural redwood forests, such as coast live oak, California buckeye, and elderberry.

Milarch is hoping that the Presidio site will demonstrate how redwood clones can be planted on a larger scale, and Troxel’s feedback will be an invaluable source of information. If a certain sub-species of redwood does particularly well there, California planters will know that variety might do well at similar planting sites around the state.

Of course, not all 75 of these trees will one day dominate here. As redwoods mature, they need progressively more space around their top branches so they can get the sunlight they need. “In five years,” he says, “their crowns will be touching.” After the trees get their park legs under them, Troxel plans to thin them selectively to give the strongest ones the best chance to make it.

When Milarch launched the Archangel project, he imagined groves of saplings like this, but as scientists and activists raised the alarm about greenhouse gas emissions, his vision began to broaden. These days, he talks more and more about pressing coast redwoods into service to capture atmospheric carbon. “We need a viable, measurable solution to reverse excess carbon, which is causing highs and lows and storms and droughts,” he says. “It’s about our children and grandchildren having a shot at life.” The signature line on his e-mail reads, “Champion Trees Are the Answer.”

Some science supports Milarch’s outsized faith in these trees. In a Science article published in July 2019, Swiss researchers estimate that 900 million new hectares of forest—a swath about the size of the continental United States—could capture enough carbon to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide levels by about 25 percent. New redwood groves could be a start, as they store a lot of carbon per acre, but they don’t thrive just anywhere and take a long time to grow.

Troxel hesitates to put too much stock in the carbon capacity of tree-planting. “As a cure-all, I’m not so sure,” he says. He stresses the importance of restoring entire natural ecosystems that include the big trees. As University College London earth scientists Mark Maslin and Simon Lewis point out in The Conversation, reforestation is hardly a magic bullet against climate change. It can take centuries, even millennia, to have its effect, and that’s time the climate problem does not have. Some of the land areas earmarked for reforestation in the Science study may end up too hot for forests by the time people get around to planting them. “Reforestation,” Maslin and Lewis write, “should be thought of as one solution to climate change among many.”

Even if champion trees aren’t an answer by themselves, Milarch is determined to see them at least become part of the answer. If there’s anything worth being downright messianic about, he figures, it’s creating eternal groves of thousand-year-old, self-replicating giants that could benefit all humankind. “We have a list of the 100 most important trees to clone. We have our marching orders. We know where we need to go,” Milarch says. “I raise my hand every morning and I say, ‘Use me.’”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook