How the 18th-Century Gay Bar Survived and Thrived in a Deadly Environment

Welcome to the molly house.

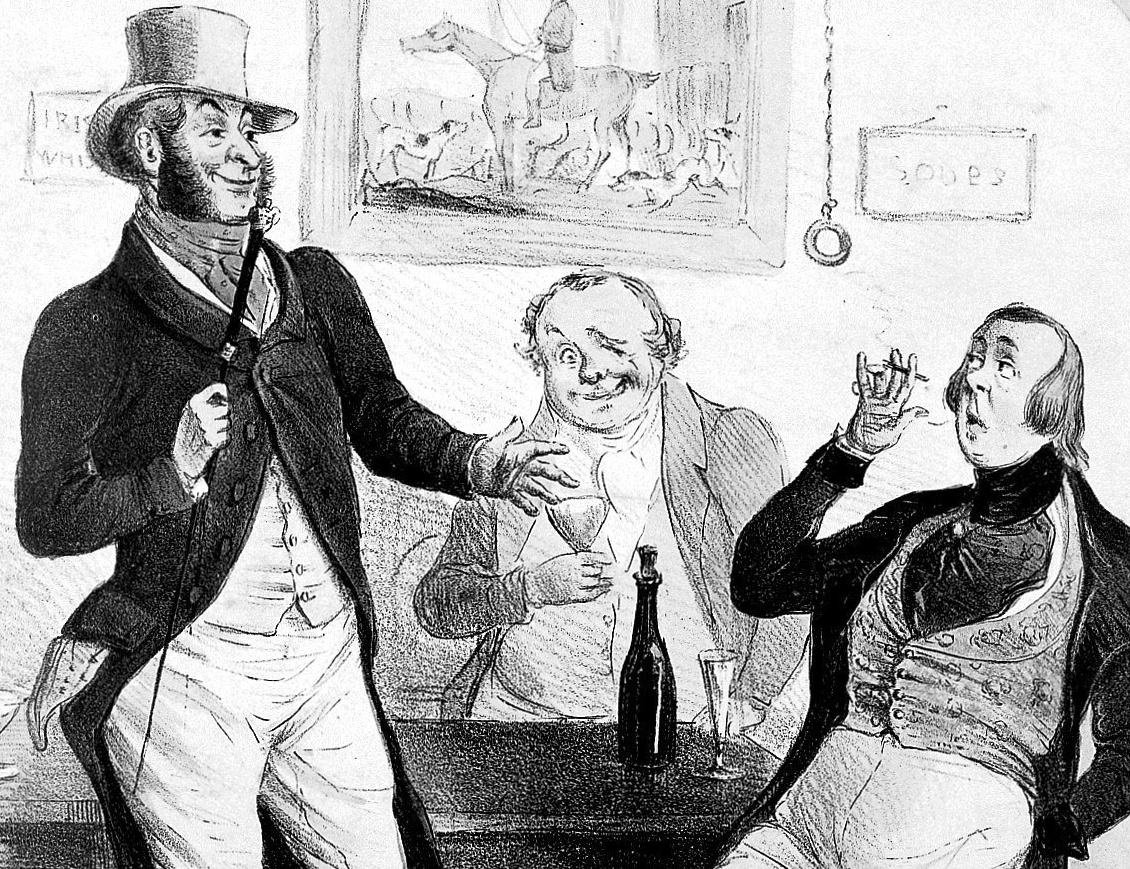

In 1709, the London journalist Ned Ward published an account of a group he called “the Mollies Club.” Visible through the homophobic bile (he describes the members as a “Gang of Sodomitical Wretches”) is the clear image of a social club that sounds, most of all, like a really good time. Every evening of the week, Ward wrote, at a pub he would not mention by name, a group of men came together to gossip and tell stories, probably laughing like drains as they did so, and occasionally succumbing to “the Delights of the Bottle.”

In 18th and early-19th-century Britain, a “molly” was a commonly used term for men who today might identify as gay, bisexual or queer. Sometimes, this was a slur; sometimes, a more generally used noun, likely coming from mollis, the Latin for soft or effeminate. A whole molly underworld found its home in London, with molly houses, the clubs and bars where these men congregated, scattered across the city like stars in the night sky. Their locale gives some clue to the kind of raucousness and debauchery that went on within them—one was in the shadow of Newgate prison; another in the private rooms of a tavern called the Red Lion. They might be in a brandy shop, or among the theaters of Drury Lane. But wherever they were, in these places, dozens of men would congregate to meet one another for sex or for love, and even stage performances incorporating drag, “marriage” ceremonies, and other kinds of pageantry.

It’s hard to unpick exactly where molly houses came from, or when they became a phenomenon in their own right. In documents from the prior century, there is an abundance of references to, and accounts of, gay men in London’s theaters or at court. Less overtly referenced were gay brothels, which seem harder to place than their heterosexual equivalents. (The historian Rictor Norton suggests that streets once called Cock’s Lane and Lad Lane may lend a few clues.) Before the 18th century, historians Jeffrey Merrick and Bryant Ragan argue, sodomy was like any other sin, and its proponents like any other sinners, “engaged in a particular vice, like gamblers, drunks, adulterers, and the like.”

But in the late 17th century, a certain moral sea change left men who had sex with men under more scrutiny than ever before. Part of this stemmed from a fear of what historian Alan Bray calls the “disorder of sexual relations that, in principle, at least, could break out anywhere.” Being a gay man became more and more dangerous. In 1533, Henry VIII had passed the Buggery Act, sentencing those found guilty of “unnatural sexual act against the will of God and man” to death. In theory, this meant anal sex or bestiality. In practice, this came to mean any kind of sexual activity between two men. At first, the law was barely applied, with only a handful of documented cases in the 150 years after it was first passed—but as attitudes changed, it began to be more vigorously applied.

The moral shift ushered in a belief that sodomy was more serious than all other crimes. Indeed, writes Ian McCormick, “in its sinfulness, it also included all of them: from blasphemy, sedition, and witchcraft, to the demonic.” While Oscar Wilde might call homosexuality “the love that dare not speak its name,” others saw it as a crime too shocking to name, with “language … incapable of sufficiently expressing the horror of it.” Other commenters of the time, trying to wrangle with the idea, seem incapable of getting beyond the impossible question of why women would not be sufficient for these men:

“’Tis strange that in a Country where

Our Ladies are so Kind and Fair,

So Gay, and Lovely, to the Sight,

So full of Beauty and Delight;

That Men should on each other doat,

And quit the charming Petticoat.”

In this climate, molly houses were an all-too-necessary place of refuge. Sometimes, these were houses, with a mixture of permanent lodgers and occasional visitors. Others were hosted in taverns. All had two things in common—they were sufficiently accessible that a stranger in the know could enter without too much hassle; and there was always plenty to drink.

Samuel Stevens was an undercover agent for the Reformation of Manners, a religious organization that vowed to put a stop to everything from sodomy to sex work to breaking the Sabbath. In 1724, he led a police constable to one such house on Beech Lane, where the brutalist Barbican Estate is today. “There I found a company of men fiddling and dancing and singing bawdy songs, kissing and using their hands in a very unseemly manner,” the policeman, Joseph Sellers, is recorded as having said in court. Elsewhere, the men sprawled across one another’s laps, “talked bawdy,” and took part in country dances. Others peeled off to other rooms to have sex in what they believed to be relative safety.

Sex may have been at the root of the matter, but everything around it—the drinking, the flirting, the camaraderie—was every bit as important. In the minds of the general public, molly houses were dens of sin. But, for their regular customers, writes Bray, “they must have seemed like any ghetto, at times claustrophobic and oppressive, at others warm and reassuring. It was a place to take off the mask.” Here, men pushed to the fringes of society could find their community.

It’s probable that a certain amount of sex work took place, though how much money really changed hands is hard to tease out. “Homosexual prostitution was of only marginal significance,” writes Norton. Instead, “men bought their potential partners beer.” More moralizing commentators mistook consensual sexual activity for more mercenary sex work, using “terms such as ‘He-Strumpets’ and ‘He-Whores’ even for quite ordinary gay men who would never think of soliciting payment for their pleasures.”

Because so many accounts of these molly houses came from people like the agent, Stevens, or the journalist, Ward, who wanted the houses closed and their customers sanctioned, they tend towards the salacious. Many focus on sexual activity or on particular aspects of this nascent gay culture that seemed shocking or foreign to these unwanted observers. One account delivered in the court known as the Old Bailey creates a vivid picture of an early drag ball. “Some were completely rigged in gowns, petticoats, headcloths, fine laced shoes, befurbelowed scarves, and masks; some had riding hoods, some were dressed like milkmaids, others like shepherdesses with green hats, waistcoats, and petticoats; and others had their faces patched and painted and wore very extensive hoop petticoats, which had been very lately introduced.” In a slew of costumes and colors, they danced, drank, and made merry.

Drag seems to have been common in molly houses, sometimes veering into kinds of pantomime that don’t quite have a modern equivalent. In Ward’s article about the Mollies Club, he describes how the men, who called one another “sister,” would dress up one of their party in a woman’s night-gown. Once they were in costume, this person then pretended to be giving birth, he wrote, and “to mimic the wry Faces of a groaning Woman.” A wooden baby was brought forth, everyone celebrated and a pageant baptism took place. Others dressed up as nurses and midwives—they would crowd around the baby, “being as intent upon the Business in hand, as if they had been Women, the Occasion real, and their Attendance necessary.” A celebratory meal of cold tongue and chicken was served, and everyone feasted to commemorate their bouncing new arrival, with “the eyes, Nose, and Mouth of its own credulous Daddy.”

At one of the most famous molly houses, owned by Margaret Clap, couples slipped into another room, two-by-two, to be “married.” In “The Marrying Room,” or “The Chapel,” a marriage attendant stood by, guarding the door to give the happy couple some privacy as they made use of the double bed. (“Often,” Norton writes, “the couple did not bother to close the door behind them.”) At the White Swan, on Vere Street, John Church, an ordained minister, performed marriage ceremonies for those who wanted them—though it’s unknown whether these nuptials were expected to last more than a single evening.

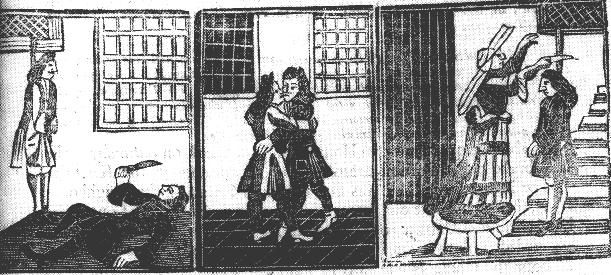

The openness that allowed men seeking sex with men to find molly houses exposed them to the risk of raids, and subsequent convictions. Police constables would occasionally swarm into the festivities, rounding up the men they found there and hauling them off to prison, where they would await trial. In the mid-1720s, there was a rash of these raids, leading many men to the gallows. Embittered informants who were intimately familiar with the molly houses would allow police to pose as their “husbands” in order to infiltrate the club. These constables would be welcomed into the fold—then return later to close it up for good and use what they had seen against the members.

In 1810, one of the most famous raids took place on the White Swan. It had barely been open six months when police stormed the place, arresting about 30 of the people they found inside. A violent mob, of which the women were apparently “most ferocious,” surged around the prisoners’ coaches as they made their way to the watch house. Two were sentenced for buggery, and put to death. A larger number, convicted of “running a disorderly house,” were mostly sentenced to many humiliating hours in the pillory, where members of the public could throw things at them. Three months after the original raid, these men were led through the streets and out onto the pillory. As they went, thousands of people formed a seething crowd, hurling whatever they could at them—dead cats, mud pellets, putrid fish and eggs, dung, potatoes, slurs. The men began to bleed profusely from their wounds. After an hour in the pillory, about 50 women formed a ring around them, pelting them with object after object. One man was beaten until he was unconscious.

These raids forced molly houses, and men who had sex with men, deeper underground. The subculture didn’t die out, but the establishments often did, or became harder to find. And then, in 1861, a sliver of light—the death penalty for sodomy or buggery was repealed and replaced with nebulous legislation around “gross indecency.” (It was for this charge that Oscar Wilde was imprisoned for two years, four decades later.) It would be another 106 years after the repeal that sex between men was decriminalized altogether in the United Kingdom, by which time the molly house was all but forgotten, and its patrons nearly scrubbed from the history books.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook