The Lesbian Pulp Fiction That Saved Lives

How potboilers and pin-ups showed gay and bisexual women they were not alone.

When Reva Hutkin’s friend from night school offered to lend her something to read, it must have seemed wholly innocent. It was the early 1960s, in Montreal, and Hutkin had recently married at 21. At the time, she says, marriage “was the only way a young woman could get out of her house.”

Her friend presented her with one salacious-looking book, then another, and another—she had “millions” of the volumes, Hutkin remembers, with the same “wonderful” covers and suggestive taglines: “twilight women,” “forbidden love,” “illicit passion.” Once Hutkin was hooked on the stories, her friend made a confession: “I think I’m like that.”

At first, Hutkin says, she was horrified. Then, she was bewildered. Finally, she wondered whether she might, in fact, be “like that,” too. Soon after, the two became lovers; Hutkin left her husband, and they began a new life together.

Not every first encounter with lesbian pulp fiction was so transformative. But for many women of the 1950s and 1960s, these slim paperbacks were pivotal, and sometimes even life-saving. Within their pages lay physical proof that they were not entirely alone in the world. “It was an era of just incredible isolation—a lot of us grew up thinking that we were the only ones,” says the writer Katherine V. Forrest, who compiled the 2005 anthology Lesbian Pulp Fiction. “The books were like water in the desert.”

In her introduction to the anthology, Forrest describes chancing upon Ann Bannon’s Odd Girl Out for sale in Detroit, Michigan. The year was 1957, and she was 18. “I did not need to look at the title for clues; the cover leaped out at me from the drugstore rack: a young woman with sensuous intent on her face seated on a bed, leaning over a prone woman, her hands on the other woman’s shoulders,” she writes. “Overwhelming need led me to walk a gauntlet of fear up to the cash register. Fear so intense that I remember nothing more, only that I stumbled out of the store in possession of what I knew I must have, a book as necessary to me as air.”

Forrest’s experience was not atypical. In a 1995 essay, Donna Allegra recounts grappling with feelings of embarrassment and shame on her way up to the front desk. But however hard she found it, she wrote, “It was absolutely necessary for me to have them. I needed them the way I needed food and shelter for survival.”

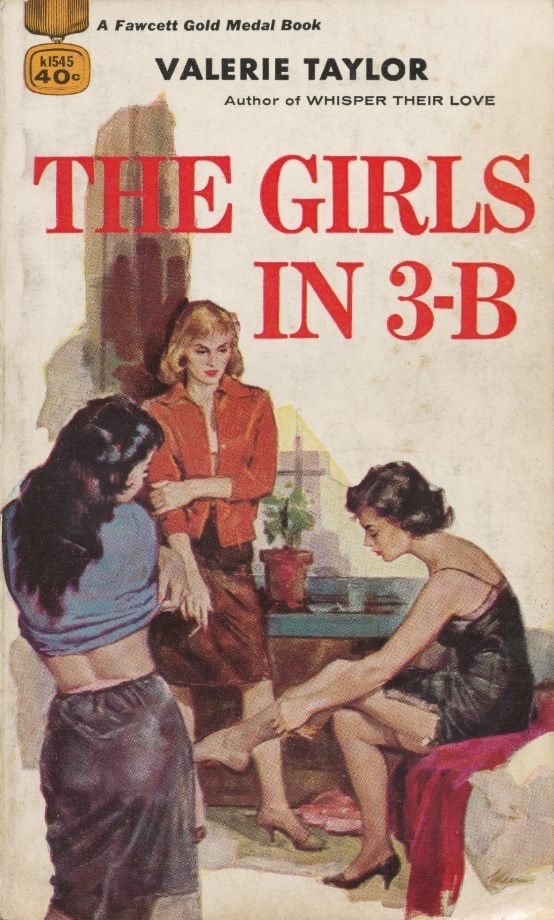

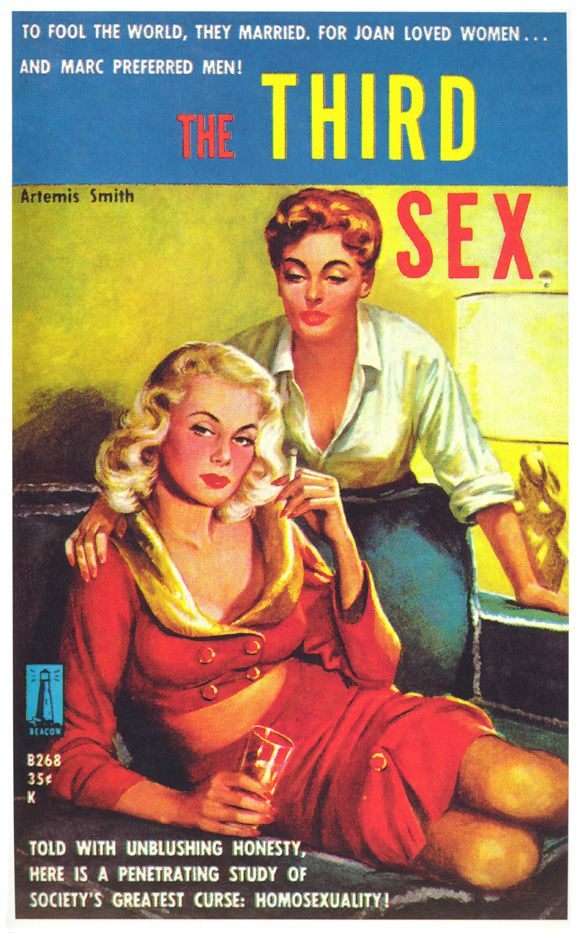

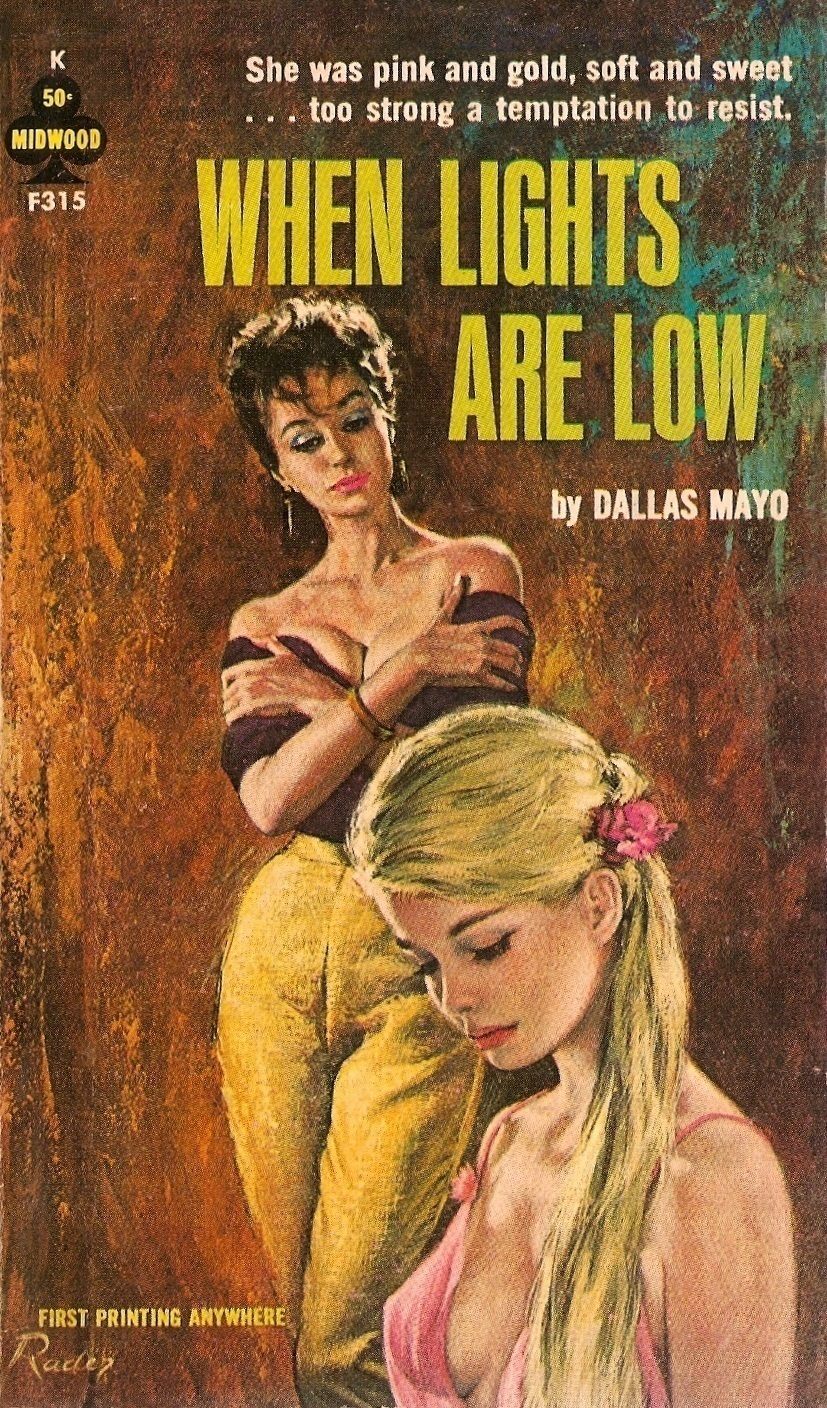

Women like Allegra and Forrest didn’t have to look far for their fix: America’s drug stores and airport bookstores sold lesbian pulp fiction quite openly. The novels were displayed cheek-to-jowl with stories of alien invasions and Nazi torture. Pulp novels had tawdry titles, conspicuous covers, and taglines that promised readers everything from “the sex traps of vacationing she-wolves” to a glimpse into “the intimate sex needs of America’s 900,000 young widows.”

Publishers likely never intended any of these books to tumble into the hands of impressionable young women, and certainly not those about lesbian love. A publishing revolution in the 1940s had put millions of inexpensive paperbacks in the pockets of soldiers—a democratic way to entertain troops that transformed the way people thought about paperback books. Pulp fiction was the end result. The books offered as many racy subgenres as there were sexual proclivities, all marketed to the men who had now come back from the war. They were cheap and disposable, designed to be read and tossed out. Yet the most successful among them sold in the hundreds of thousands or even the millions—and many of these were lesbian pulps.

Tereska Torrès’ 1950 novel, Women’s Barracks, is often cited as the first example in the genre, and the one that launched hundreds more. Inspired by her own experiences of the war, the novel tells the tales of torrid affairs between butch officer types and their femme subordinates. It sold some 2.5 million copies, and was the 244th best-selling novel in the United States before 1975, despite being banned for obscenity in multiple states.

Marijane Meaker’s Spring Fire, published two years later under her pseudonym Vin Packer, sold a similarly eye-watering 1.5 million copies, while the male novelist Jess Stearn’s The Sixth Man spent 12 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. The potential for huge sales shone a light on these books and earned the “frothy” novels places on the review pages of even quite serious newspapers. In 1952, a male reviewer at the Times called The Price of Salt by Claire Morgan (pseudonym for thriller writer Patricia Highsmith*) “pretty unexciting”—though he was likely far from its intended readership. (It forms the inspiration for the British film Carol, released in 2015.)

Lesbianism was such a popular theme for pulp, one writer explained to the New York Times in September 1965, because the reader “gets two immoral women for the price of one.” For many readers, this may have been the case—certainly, a significant portion of the books were as homophobic as their covers. Set in women’s dorm rooms or prisons, a significant portion are seamy “true accounts,” written by men with women’s pseudonyms, and marketed as cheap thrills to male readers.

But perhaps 50 titles were written by women, for women. The scholar Yvonne Keller calls these “pro-lesbian,” as opposed to the more common “virile adventure.” The pro-lesbian novels are the ones that changed women’s lives, and in so doing, passed the test of time—the books of Marijane Meaker, Valerie Taylor, Artemis Smith, and Ann Bannon. These authors wrote for women, and it showed. “I did hope women would find them and read them,” says Bannon, a doyenne of the genre, now in her mid-eighties. “I wasn’t quite sure enough of my skill or ability to reach them, or even how widely the books were distributed, to hope that they would do some good in the world. But I certainly had that in the back of my mind.”

In fact, she says, she scarcely thought about her male audience, and so was blindsided by her publishers’ choice of cover illustration. The characters within were complex and three-dimensional, but those on the covers were either waifish and gamine, or pneumatic and heavy-lidded with passion. “That artwork was meant to draw in men through prurient interest,” she says—a far cry from her original intent. But if as many men had not bought them, she says, they might never have been so widely disseminated, or have fallen into the hands of the people who needed them the most.

In burgeoning lesbian communities, pulp novels were treasured and passed from person to person. The author Lee Lynch, now in her 70s, was part of a group of “gay kids” in New York, who met up and sat in Pam Pam’s, a sticky ice-cream parlor on 6th Avenue. “I just remember the milling about that took place there, of kids, of gay kids,” she says. “We were not ashamed, together. Maybe it was a folly of however many, of the multitudes, that when we were all together, even if we didn’t know each other, we could talk about the books.” They’d buy flimsy softcovers from a newspaper store and read the books until they were dog-eared and tatty—before secreting them away, far from their families’ prying eyes.

Lynch describes herself as hugely fortunate to have had this kind of circle, including a first girlfriend, Susie. But for those who didn’t, the books were perhaps even more valuable. In a 1983 essay in the lesbian magazine On Our Backs, Roberta Yusba writes: “The pulps also reached isolated small-town lesbians who could read them and see that they were not the only lesbians in the world.”

In 1983, the lesbian publisher Naiad Press reprinted a selection of the best lesbian pulp novels. Bannon’s were among them. These books were cherished not necessarily for their literary value, but as an early blueprint for lesbian life, all centered around a utopian Greenwich Village. Without older lesbians or bisexual women within their community, lesbian pulp fiction was often the only model women had. And while the books weren’t perfect, they were significantly better than the vacuum that had preceded them.

In the 1950s, Bannon says, homosexuality was often spoken of as a kind of pathogen: You weren’t just sick, you were contaminated and contagious—especially to the young and impressionable. “You didn’t want to have, or to acknowledge having, gay friends, or to be consorting with gay people, or defending them,” she says. “And I think at the root of that was a lot of anxiety about converting children to a gay life, because it seemed to be so seductive and fascinating that merely having contact with a gay person or reading a gay book would lead you down the wrong path.”

Many of the women who read these books and came out to their peers in the 1960s and 1970s never told their families, dodging questions for decades about their apparent singledom and lack of children. Though Lynch remembers prevailing feminist wisdom that said that you had a responsibility to come out to your parents, she struggled to find a way to do so that wouldn’t “basically ruin [her mother’s] life.” Her mother had, on one occasion, walked in on Lynch with Susie, that first girlfriend, but chose to ignore what she saw. “She would have thought I was going to burn in hell,” she says.

Even though Bannon wrote lesbian pulp fiction for lesbian and bisexual women, coming out was impossible. She had married an engineer shortly after graduating from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, then written her first book, Odd Girl Out, in her home in suburban Pennsylvania at 22. It was published under a pseudonym. (Her birth name is Ann Weldy; she chose Bannon from a list of her husband’s customers.)

At first, Bannon says, she hoped the books might be a launchpad into a career as a writer. “I did think I could write, and I did want to do it, and I did need to get started somewhere. I was about as ignorant as anybody could have been back then,” she says, laughing. She had read Vin Packer’s Spring Fire and wrote to its author, Marijane Meaker, who put her in touch with her editor at Gold Medal Books. Odd Girl Out would go on to be the publisher’s second best-selling title of 1957. It launched a series of six books, later known as the Beebo Brinker Chronicles, after their charismatic heroine, who shows up in New York at 18 and finds her way there as a butch lesbian.

Throughout this time, Bannon was living a kind of double existence, split between married life in Pennsylvania, and occasional weeklong visits to see friends in Greenwich Village. Hearing her talk about these visits, you get the sense that they were as much to research the books, as she told her husband, as they were an exploration into what could be, what alternatives she might have had.

Bannon recalls walking through the Village alone late at night—“I mean, I must have been out of my mind, but I wasn’t even afraid”—and staying in bars until two or three in the morning, talking to women for inspiration for the books. She was surrounded by people who were “young and adventurous and willing to try things” and, she says, “I was sort of pretending to be single. Those trips to the Village, I really was beginning to wonder if I’d done the right thing to get married, and trying to rethink my life a little bit.”

Her husband never read the books, and only really reconciled himself to them when they began bringing in significant amounts of money. Bannon remembers tense evenings typing away with the children in bed, while her husband sat in the other room and watched television. Eventually, the marriage broke down, and Bannon abandoned her writing career for the good of her children, and a successful career in academia.

But this brief foray into fiction had helped lay the ground for decades of lesbian writing, as gay and bisexual women came to realize how much they needed to be represented in print. Lynch remembers going from one section to the next in libraries and bookstores, in pursuit of some kind of literary mirror. “I was driven,” she wrote in an essay, “searching for my nourishment like a starveling, grabbing at any crumb that looked, tasted, or smelled digestible.” She read the pulps and what few other early lesbian novels there were, such as Radclyffe Hall’s 1928 The Well of Loneliness—but venturing deeper into the library yielded “crumbs” that were sometimes quite toxic. “I would go to the criminology section,” she says, “in the sociology area, because there were lesbians in those books.”

She remembers one rattling 45-minute subway ride back to Flushing, Queens, from the Village, with her then-girlfriend, Susie. “We were acting out, you know, being out lesbian kids in front of a carload of presumably straight people,” she says. “All of a sudden, Susie said to me, ‘You know, we’re actually juvenile delinquents. What we do is against the law.’” She pauses. “I hadn’t thought of it like that before—I actually probably didn’t even know that.” By the age of 15, she says, “Our self-image was already, ‘You’re a criminal, and sick, and rejects, you’re societal rejects.’ To find anything about ourselves was extremely exciting.”

The pulps weren’t like that. Their messages might have been mixed, but they acknowledged feelings these young women had without writing them off. In her introduction to Lesbian Pulp Fiction, Forrest describes the books as life-saving: In some cases, this was literally true. Bannon recalls a young woman who later became a good friend. She had reached a point of “absolute despair,” she told Bannon, and planned to cast herself off the big bridge that ran through her city. Then, on the day she resolved to do it, she passed a drugstore and saw Odd Girl Out, Bannon’s 1957 novella, on the shelves. She bought it, sat down, read the whole thing—and then went home for dinner.

“You hear things like that and it just turns your heart over. I don’t know how many there were who went through that, but that anyone should have gone home for dinner, instead of jumping off the bridge…” says Bannon, her voice catching. “Oh, my goodness—I mean, you never get over that.”

The impact of that representation was tremendous. Lesbian pulp novels appear again and again in lesbian memoirs and personal essays, always with the same mingling of pleasure and pain. In Kate Millett’s 1974 autobiography, Flying, for instance, she describes herself hoarding them, “because they were the only books where one woman kissed another, touched her, transported to read finally in a book what had been the dearest part of my experience recognized at last in print.” She hid them away in a drawer until she left the country for Japan. “Afraid the sublet might find them, I burned them before I set out.”

In the best cases, the books weren’t just proof that lesbians existed, but that they could be proud of who they were and what they wanted. Ten years before Stonewall, Artemis Smith’s 1959 novel Odd Girl, shows this confrontation with the hero, Anne, and her father:

“No daughter of mine is going to be a—a lesbian!” He said the word with intense hate.

“I’m afraid you have nothing to say about that,” Anne said quietly. “I am what I am.”

“You’re a victim of this—this awful woman,” her father sputtered. “She has you hypnotized!”

“No, Dad,” Anne continued, quietly, “I have always been this way. I won’t be changed by you or anyone else. This is the first time my life has really felt right and happy.”

“You are breaking the laws of nature—” her father said.

“The law I’m breaking is against nature,” Anne returned, strongly. “The law will have to be changed.”

But not every book was quite so affirming, nor quite so radical. The ones by men made no real effort to reach female readers, and even women writers were at the behest of their publishers, who forced them to introduce sad endings. Readers, they said, didn’t want to see these women happy and fulfilled by their lesbian dalliances. So heroines threw themselves off high things, renounced their sexuality, or were abandoned by their lovers and went mad with grief. Even novelists with the very best intentions were not immune to these demands. By the time Bannon was writing, she says, the pressure had lessened only a little. She wasn’t required to kill off her protagonists, at least, but giving them a happy ending was virtually unfathomable.

All of this, Lynch writes, had a somewhat ambivalent effect on both her incipient pride and her self-esteem. On the one hand, the books were validating, insofar as “they acknowledged the existence of lesbians.” On the other, they left little room for hope. “The characters were more miserable than Sartre’s, and despised as well.”

For Hutkin, in Montreal, who had no lesbian community to speak of, the books provided a deeply depressing exemplar. They changed her life only by showing her that “another kind of me” was possible, she says. “Those books had terrible, awful endings. No lesbian ever should buy those books! They all had to be saved by some man, or some horrible tragedy befell them. I mean—they weren’t happy books, or anything. They were awful.” Even when she realized that she had feelings for her friend at night school, with whom she later spent almost a decade, “I fought with that all the way. I didn’t want to be like that.”

Characters’ love lives mostly played out in bars, and particularly in Greenwich Village—and so, desperate to find their people like them, Hutkin and her girlfriend traveled from Canada to the Village in search of “the lesbians.” In the books, she remembers, there was a clear binary between butches and femmes. “There seemed to be nothing in between, so we dressed appropriately.” Her girlfriend put on a dress, and Hutkin selected the most masculine outfit she owned: pants, and a red blazer. The journey took all day, but when they arrived, the lesbians were nowhere to be found.

“We just looked around, and didn’t see anything that looked like dykes,” she says, laughing. “We were pretty innocent, we knew nothing. We were in our early 20s and had never encountered any of this stuff, except in these books, which obviously weren’t really true to life.” From the books, she says, they assumed it would be obvious, that you could walk down the street and see bars and restaurants with “Lesbians!” lit up in lights. Instead, despite asking passers-by and taxi drivers where they were, they didn’t find the lesbians—so they spent the night in New York, and then went back to Canada.

Of course, there were lesbians in Greenwich Village, even if Hutkin and her partner didn’t come across them. Much of Bannon’s inspiration for the books came from little details she saw while visiting. It’s hard to acknowledge now, she says, but these darker aspects of her characters’ lives weren’t necessarily unrepresentative: It was simply very hard to exist as a gay or lesbian person at that time. Knowing how to show that wasn’t always easy.

“I remember learning that high school kids, for example, would come down to Greenwich Village on the weekends,” she says. “They walked around where they knew lesbians were living, and terrorized them, and threatened to come back in the night, and kill them, or kill their pets.” This discovery made its way into one of her books—in a fashion. In a perverse, alcohol-fueled attempt to win back a lover, her heroine, Beebo Brinker, brutally kills her own dog. “I have been sorry ever since,” Bannon says, “because it wouldn’t have been the woman herself. It would have been one of these gangster kids egging each other on. And even the kids would have grown up and been scandalized that they did such an ugly thing.”

The books, she says, are a product of their environment, and of a time when people were under colossal stress from constant marginalization—a cultural context in which straight people genuinely believed that their LGBT peers had “perversely chosen and pursued their lives” to defy the norms of those around them. “That these people were deliberately attracting attention to themselves and that whatever punishment they received they deserved.” It’s hard for the books not to reflect that context, Bannon says. “It takes a while to step out of that mindset—to get away from it.” She pictures herself looking back at the time as from the summit of some imaginary hill. “You begin to realize that you were being fed a line of nonsense because people didn’t know any better.”

Their re-release in the 1980s, and Bannon’s subsequent “outing” to the general public as Ann Weldy brought that tension to the fore. Some 1980s readers thought of them with tremendous affection, certainly—but others saw them as a vestige of a more unhappy time, with a roaring undercurrent of homophobia just barely out of sight. The journalist Joy Parks, in one 1980s review, describes her teeth being “set on edge” by their apoliticism, and the way these women are consistently referred to as “girls.” “These romances have a genuine, down to earth, life-in-the-raw quality, plus love scenes that appear very fresh and (I hate to say it) rather sweet in their innocence and lack of graphic detail,” she writes. “But the fringe life of the lesbian of the ‘50s and ‘60s lacks something vital: self-love, pride, dignity.”

Around the same time, the writer Andrea Loewenstein, who had loved the books in her youth, struggled to respond to friends who found them “boring and badly written.” Other acquaintances, she wrote, were angered and upset by them and the bitter past they represented. But ignoring that challenging recent history, she writes, borders on revisionism. “It is important for us, as readers, to remember that other lesbian writers were drawing different conclusions from the same … life evidence,” Loewenstein concludes. “But it is also important to understand and to bear witness to the kind of pain which is behind the clichéd writing in these “pulp” novels. This pain and self-hatred is not our only past. But it is a part of it.”

The novels have two important legacies: First, they showed lesbians that hope and community were possible. And second, they helped to kick-start a rich tradition of lesbian writing. As a teenager, Lynch loved these books, writing down cherished passages on yellow note cards. (She still has them today.) As an adult, she says, they instilled in her a commitment to writing books that could inspire lesbians, in a way that she had never had. “The books were bombarding you with negative stereotypes,” she says, “but inside, I was in love with my girlfriend. We were really proud of being gay.” Today, she says, she identifies as a lesbian writer “who only wants to make lesbians happier, by reading my books. The positives came out of the negative, I think.”

Though it may have started with Beebo, Laura, Stephen, Carol, and so many other troubled heroines who were doomed to suicide, misery, the loss of a child, or marriage, the same was not true for many of their readers. Instead, these sad stories were simply a prologue to their own happy ones.

It was a “rocky beginning” in Detroit in the 1950s, Forrest says, but it had a happy ending. “I’ve met some wonderful women along the way, and have been very lucky to have been loved by a few of them. It’s been a good life.” Hutkin never did find the legendary lesbians of Greenwich Village, but eventually found a community of people like herself through the women’s movement. She has a daughter and a grandchild and lives with her partner of over a decade in Victoria, Canada. Lynch had a successful career as a writer and novelist and eventually married. She lives with her wife in the Pacific Northwest.

After Bannon’s divorce, she did not remarry and instead threw herself into her academic work. She thinks of the books almost as an alternate life she constructed for herself on the page, “bits and pieces of which I would have liked to have lived. It became sort of a satisfying outlet, where perhaps, looking back, it should have been a lived experience instead of an imagined experience. It was to some degree,” she says, “in those brief little vacations when I was up there and was fully into it. But it was also—it seemed just beyond my reach, something you could see through a window, but you couldn’t pass through. You could visit, but you couldn’t live there.”

* This article was updated to state that Claire Morgan was a pseudonym for Patricia Highsmith.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook