See Two Decades of San Francisco’s Wildest Queer Halloween Parties

The rise and demise of the night of the living dead.

As far back as 1948, Halloween held a special magic for San Francisco’s LGBT community. That one night was like “a chapter from a Cinderella story,” writes Randy Shilts, in his biography of the activist and politician Harvey Milk.

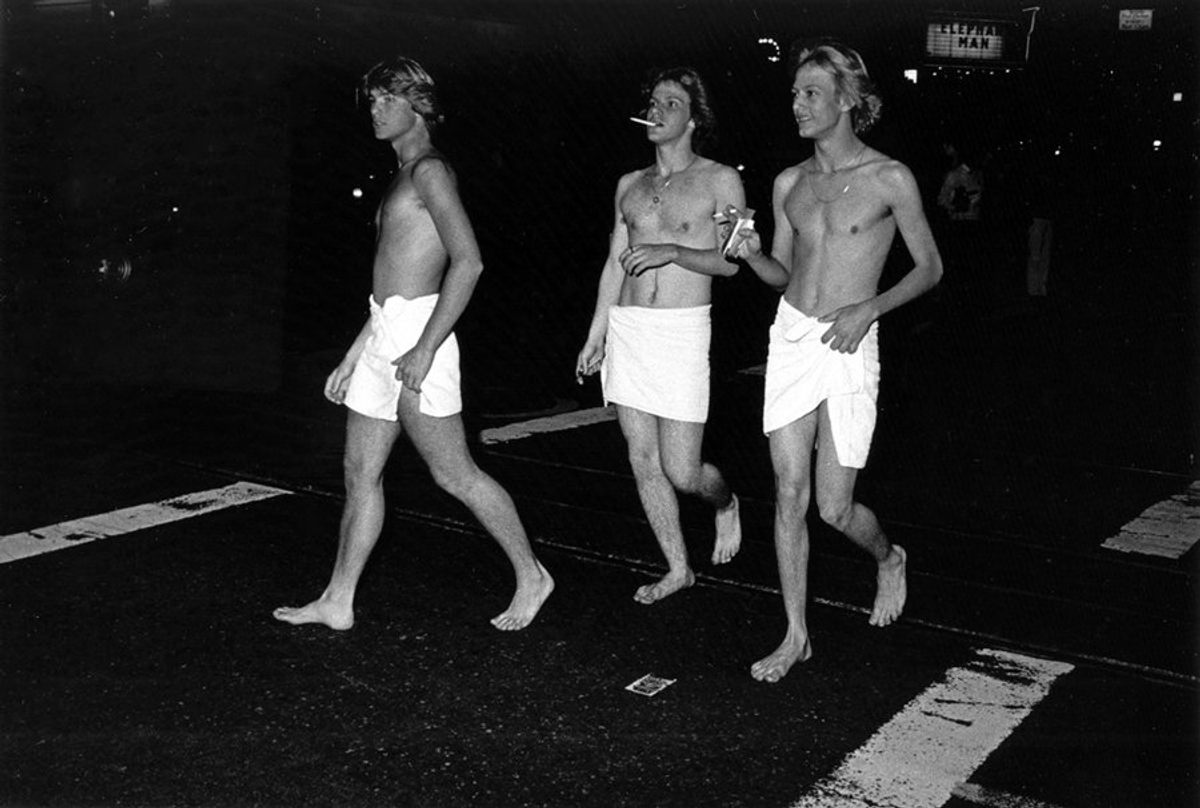

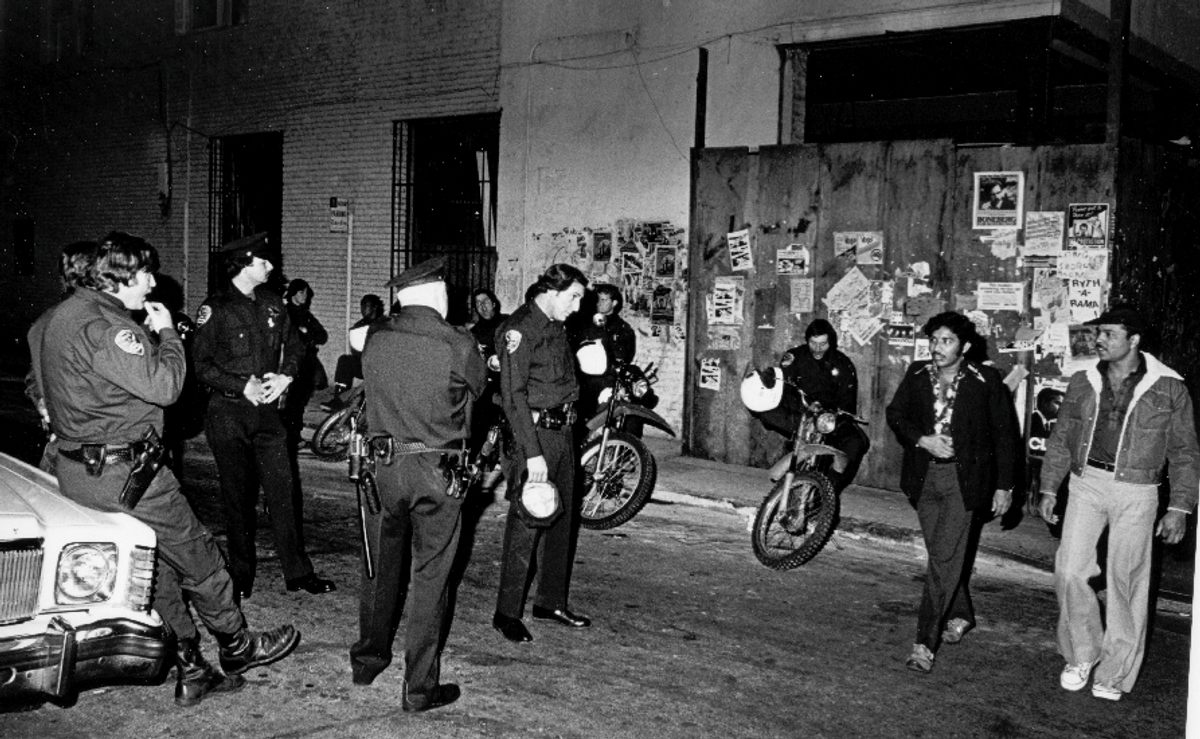

From the late 1940s until at least the decriminalization of California’s sodomy laws in 1976, friction between the mostly Irish-Catholic police department and the city’s queer citizens intensified. Police were often openly homophobic while, in the meantime, more and more young LGBT people were moving to the city, seeking the opportunity to be themselves. Clashes ensued. But, on Halloween, the residents of Polk Street had a free pass. It “had been staked out years before as the homosexual high holiday,” Shilts explains: “gays did, after all, live most of their lives behind masks.”

The night began with a traditional send-off from the chief of police: ‘“This is your night—you run it.”’ And for the rest of the evening, at a time when it was illegal even for gay people to “peaceably assemble,” these San Franciscans were free to celebrate and carouse in a tremendous street party—until the clock struck midnight. “When the hours shifted from October 31 to November 1, the iron fist of Lilly Law,” the then-current gay slang for a policeman, “would fall again.”

For the next six decades, that night would be a highlight of San Francisco’s gay calendars—until, in 2007, when the Halloween party was cancelled by city officials, due to overcrowding and repeated incidents of violence.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Polk Street had played host to queer Halloween festivities. But homophobes began causing trouble, setting fire to gay-owned businesses or lurking at the edge of the crowd, waiting to attack people they believed to be gay or lesbian. In 1976, tear-gas canisters were let off.

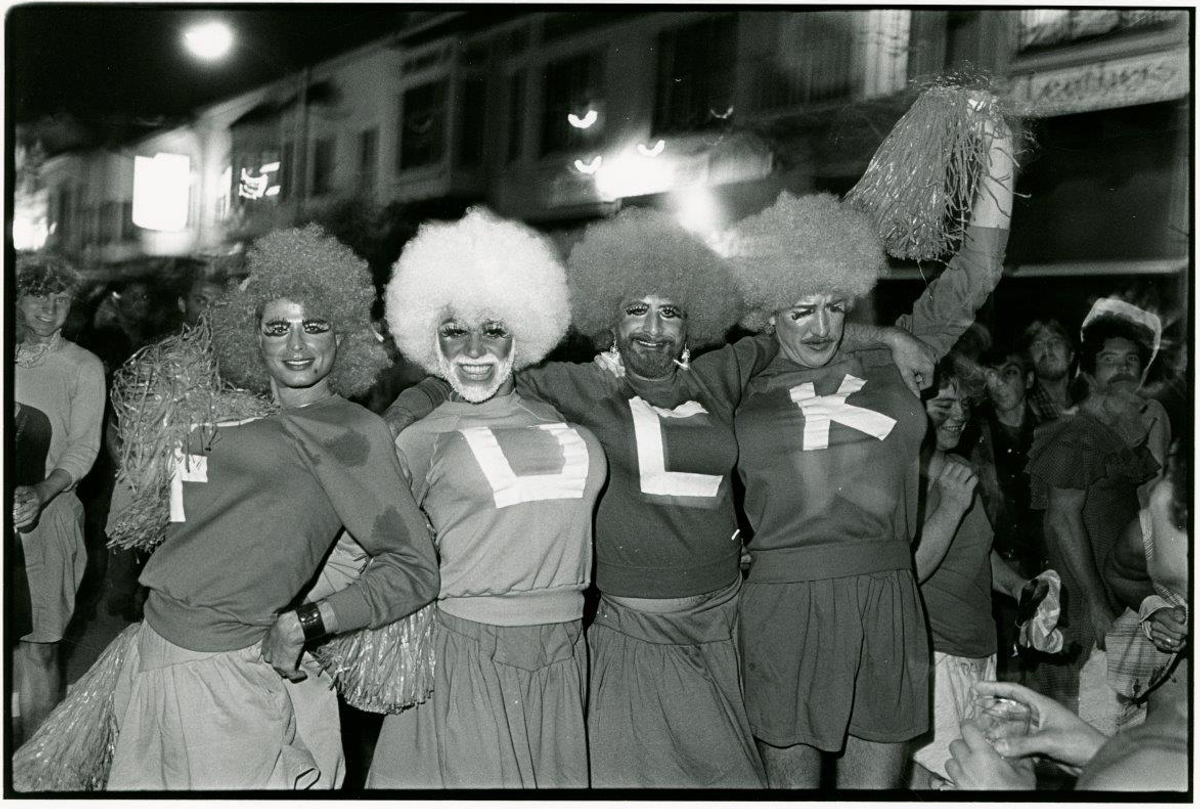

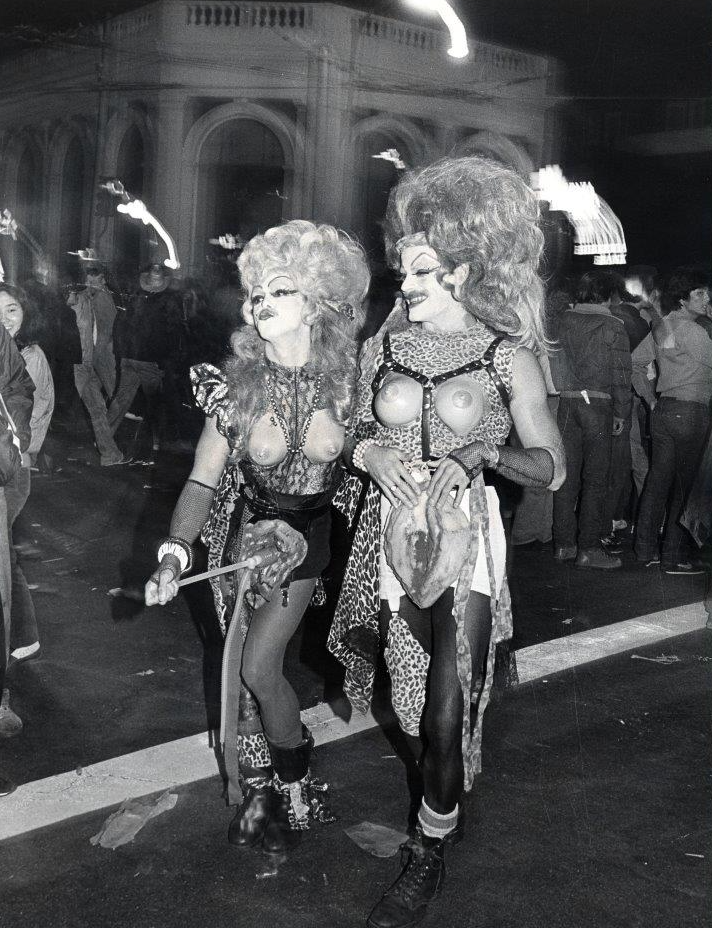

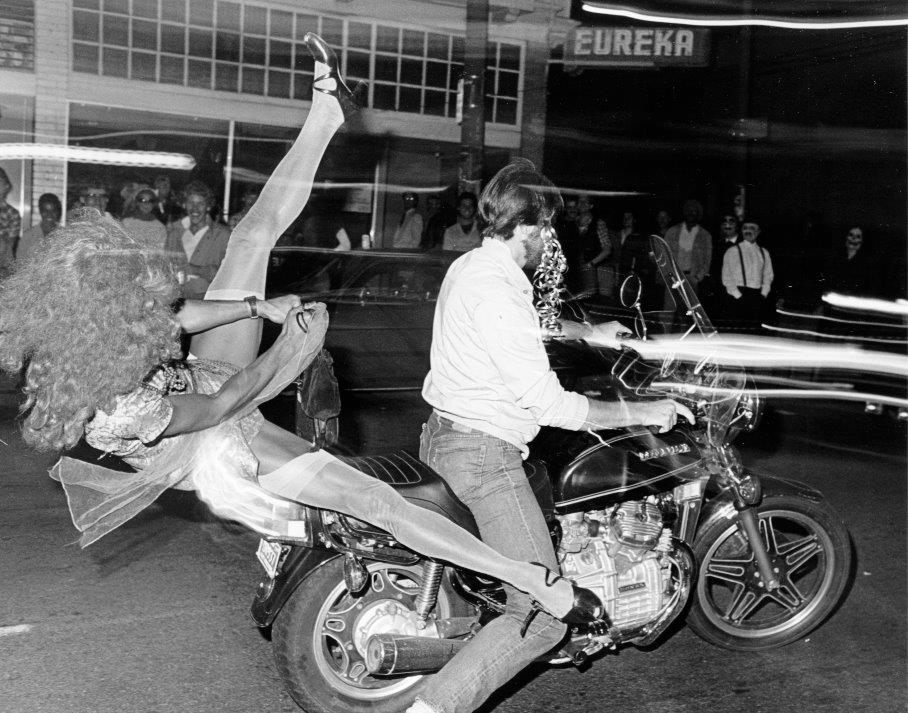

Sometime that decade, the party relocated further south to the Castro. A new era of sexual openness had brought a wave of gay migration crashing down on San Francisco’s shores, ready to take to its streets. By 1980, the tiny Castro neighborhood would have 30,000 people celebrating Halloween. The children’s party that had been held there for decades was swiftly cancelled as drag acts, trashy nuns, and assless chaps stormed the strip.

But in the Castro, too, the Halloween joy had a limited shelf life. Within 15 years, people began to fear that Halloween’s days in the Castro might be numbered. “This annual Halloween party is a victim of success,” reported the San José Mercury News in 1995. “It simply got too big for its britches—although not all partygoers have bothered to wear them. Part of the event’s appeal has been its disdain for good taste and conventional modesty: The only dress code has been that imposed by the chilly night air.” That initial 30,000 was now closer to half a million.

Revelry bred raucousness; raucousness bred rioting. Stabbings and misdemeanors in the Castro on that one, magical night had led to a need for increased police presence. Streets were closed on an “emergency” basis, with no one individual or group prepared to take responsibility. Something had to be done: In 2007, the city of San Francisco spent $40,000 on television ads and fliers encouraging people to stay away from the area, in an official campaign called “home for Halloween.” The magic was over.

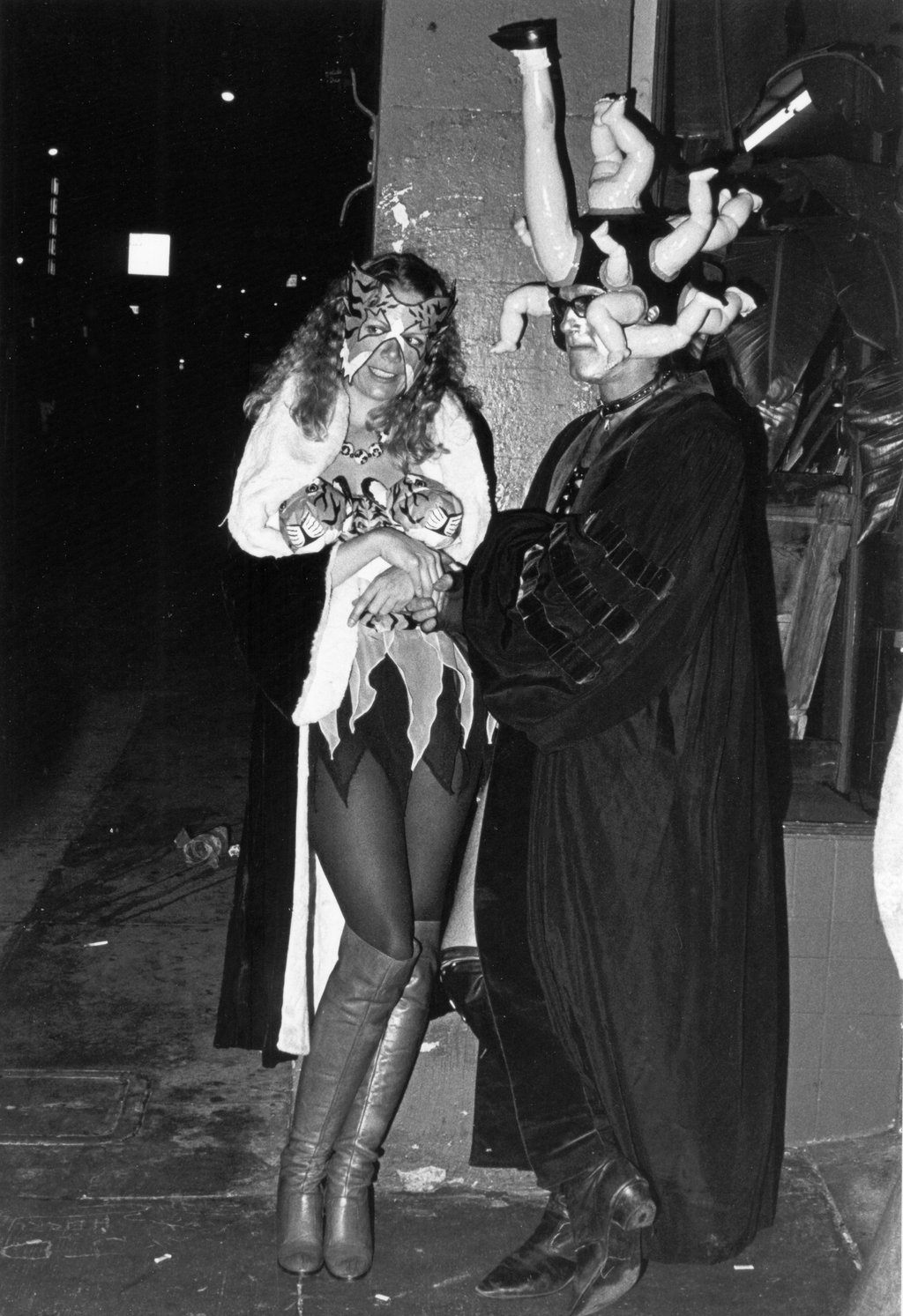

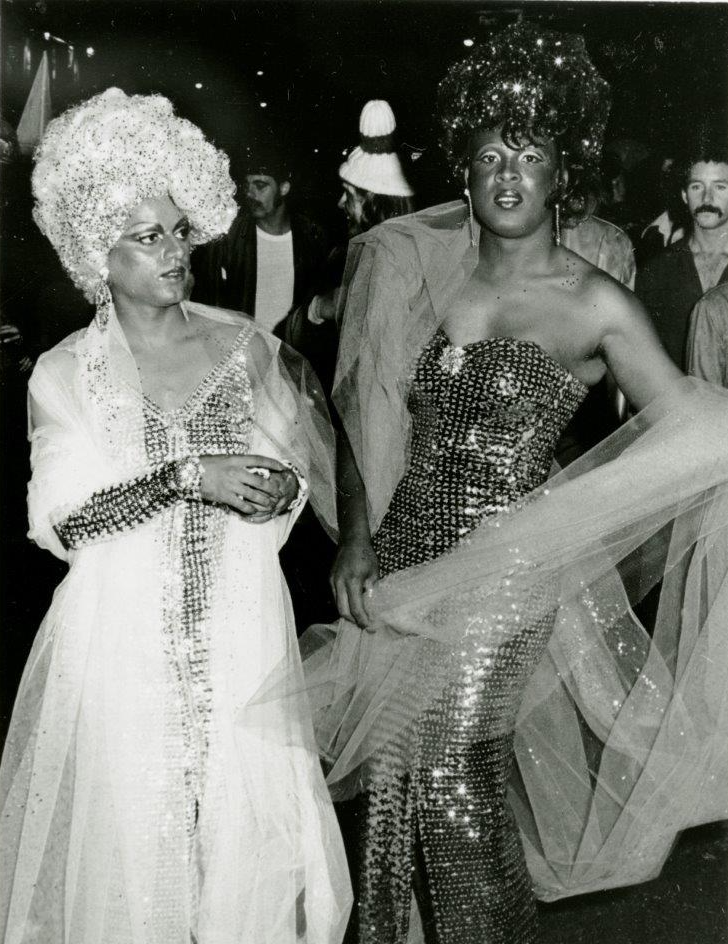

For a long time, Halloween held a special importance for the community, perhaps dating to that early police reprieve. “Queens worked for weeks on their costumes, and made every effort to be the ‘Best of Show’,” remembered photographer Donald “Uncle Donald” Eckert, who died last year, on his blog. “There was still a lot of police harassment in the 1970s and wearing ‘drag’ in public was sometimes used as grounds for arrest. So, Halloween was the only day of the year that it was ‘safe’ for a man to go out in public wearing a dress, or at least this was the accepted ‘wisdom.’” Police had, from the 1940s, violently enforced an archaic ordinance that forbade posing as a member of the opposite sex: drag queens responded by pinning paper notes to their dresses that read: “I am a boy.”

The other outcome of the law, writes David J. Skal in Halloween: The History of America’s Darkest Holiday, was “a distinctly over-the-top drag aesthetic … Since travesty drag didn’t fool anybody, it couldn’t be considered a legitimate attempt at identity fraud.” Eckert recalled high-octane drag queens and their tuxedo-ed escorts making dramatic entrances in the neighborhood’s watering holes: “They would rent limousines and drive from bar to bar showing off their elaborate creations. The custom grew in popularity and people would gather outside bars and watch the exotic parade of furs and rhinestones and feathers and glamour.”

Today, the so-called “exotic parade” has been retired once and for all. On October 31, traffic flows normally down the street; bars and nightclubs are open as usual; party-goers seek alternative events for HallowQueen parties elsewhere in the city. The final death knell was in Halloween, 2007. For the first time, bars closed early, parties moved out of the area, and 500 members of the police force patrolled the streets to keep the peace. With the Castro’s Halloween’s festivities gone, it was, instead, a ghost town.

These images from the San Francisco library archives recall the high spirits of queer Halloween on Polk Street and in the Castro throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook