Found: The Remains of an 18th-Century English Coffeehouse

Archaeologists think that calf’s foot jelly was its signature dish.

As Sting explained in “Englishman in New York,” you can tell which side of the pond one hails from based on drinking habits alone. The stereotype says that Brits take tea and Americans dig coffee. Yet up until the 19th century, it was coffeehouses that dominated English high streets. They weren’t the same as today’s café’s, which preside once again, but were more like inns that served a variety of drinks and food. Now newly found relics of one of these establishments from the 18th century are illuminating the role they played in public life.

Archaeologists conducting a survey of the Old Divinity School of St. John’s College at the University of Cambridge found the remains of a cellar filled with more than 500 objects, including drinking vessels used for coffee, tea, and chocolate, a few dishes, some animal bones, and a remarkable collection of 38 pots.

“Coffeehouses were important social centers during the 18th century, but relatively few assemblages of archaeological evidence have been recovered and this is the first time that we have been able to study one in such depth,” said Craig Cessford, from the Cambridge Archaeological Unit, in a press release.

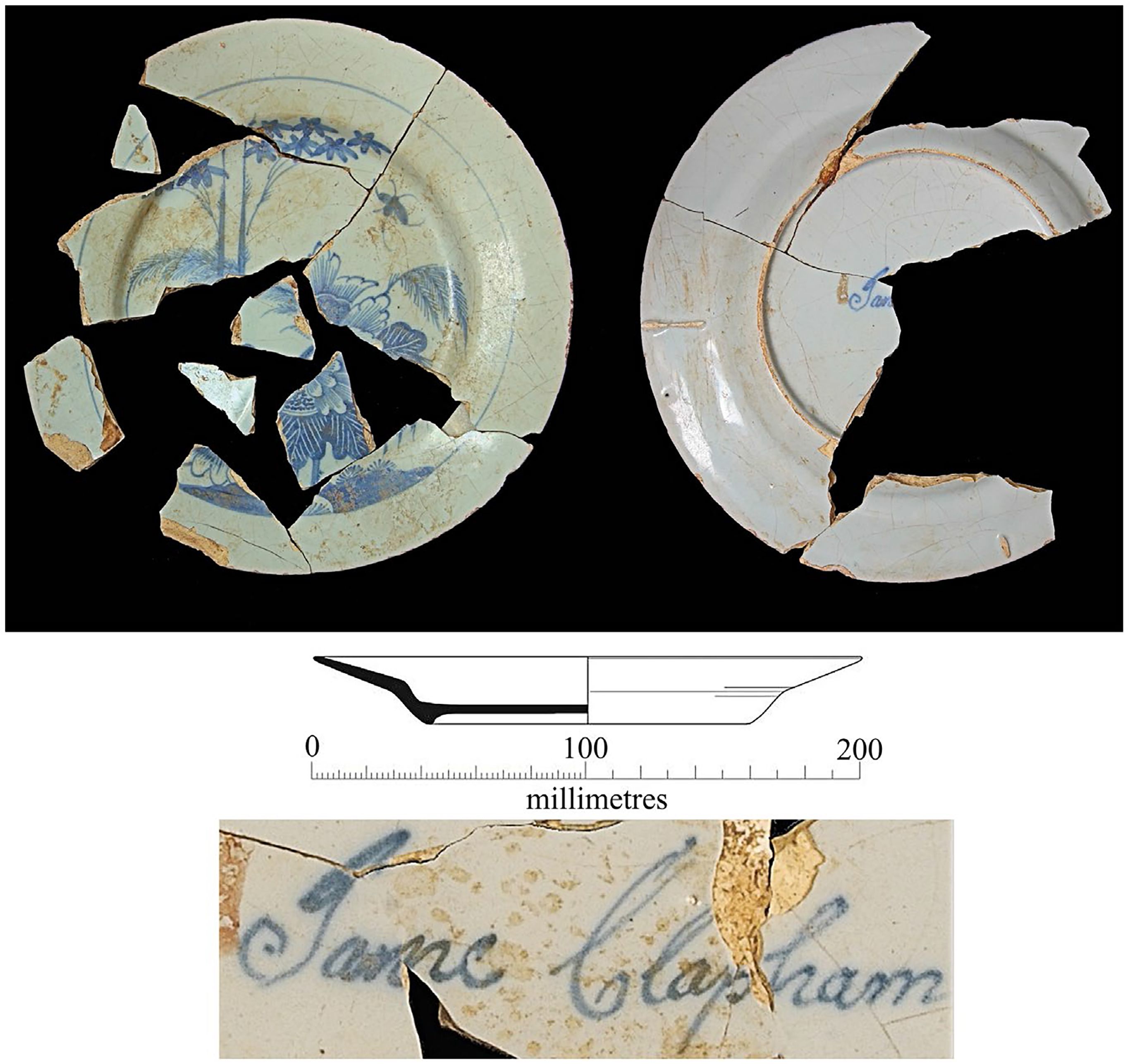

Cessford and his team are now studying the artifacts to better understand the role that cafes such as “Clapham’s”—the name of the establishment—played. “In many respects, the activities at Clapham’s barely differed from contemporary inns,” the archaeologist said. “It seems that coffeehouses weren’t completely different establishments as they are now—they were perhaps at the genteel end of a spectrum that ran from alehouse to coffeehouse.”

That’s why more than just cups were found at the site. There were tankards, wine bottles, clay pipes, and as many as 18 jelly glasses, which, together with bones from the feet of cattle, lead researchers to believe that calf’s foot jelly, a gelatin-based dish, was probably a signature item. Interestingly, the fact that vessels for tea were almost three times as common as those for coffee suggests that, though Clapham’s was nominally a coffeehouse, tea had begun its takeover.

Written evidence reveals that the café, run by William and Jane Clapham from 1740 until the late 1770s, was a popular hangout for students and locals alike. A 1751 student publication read: “Dinner over, to Tom’s or Clapham’s I go; the news of the town so impatient to know.”

Surprisingly, there was no evidence of newspapers or pamphlets, even though their rise is often linked to coffeehouses. Items associated with reading, such as book clasps, had been found at inn sites, for example, but not here. “We need to remember this was just one of thousands of coffeehouses and Clapham’s may have been atypical in some ways,” Cessford added. “Despite this it does give us a clearer sense than we’ve ever had before of what these places were like, and a tentative blueprint for spotting the traces of other coffeehouse sites in archaeological assemblages in the future.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook