Savvy Bacteria Parents Distribute Damage Unevenly Among Their Children

Like Lucille Bluth, bacteria play favorites like crazy. (Video: Youtube)

Compared to human dynamics, bacterial family-making seems like a walk in the park: grow, split in half, repeat. No biological clock, no complicated debates about egg-freezing, no “work-life balance”. But researchers in Dr. Lin Chao’s lab at the University of California San Diego have found that the reproductive strategies of bacterial are more complex–and more cutthroat–than previously thought.

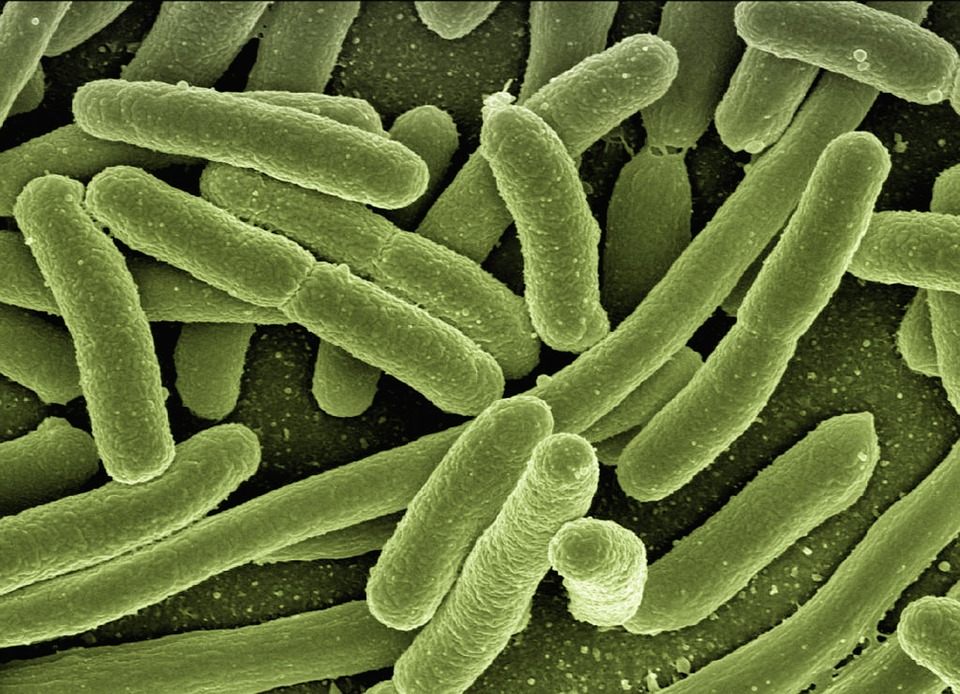

In ongoing studies of E. coli colonies, they have watched as replicating bacteria build some kids better than others, distributing accumulated damage unevenly among their descendants in order to improve collective survival. What was formerly considered an equal division is more like some kind of bacterial Sophie’s choice.

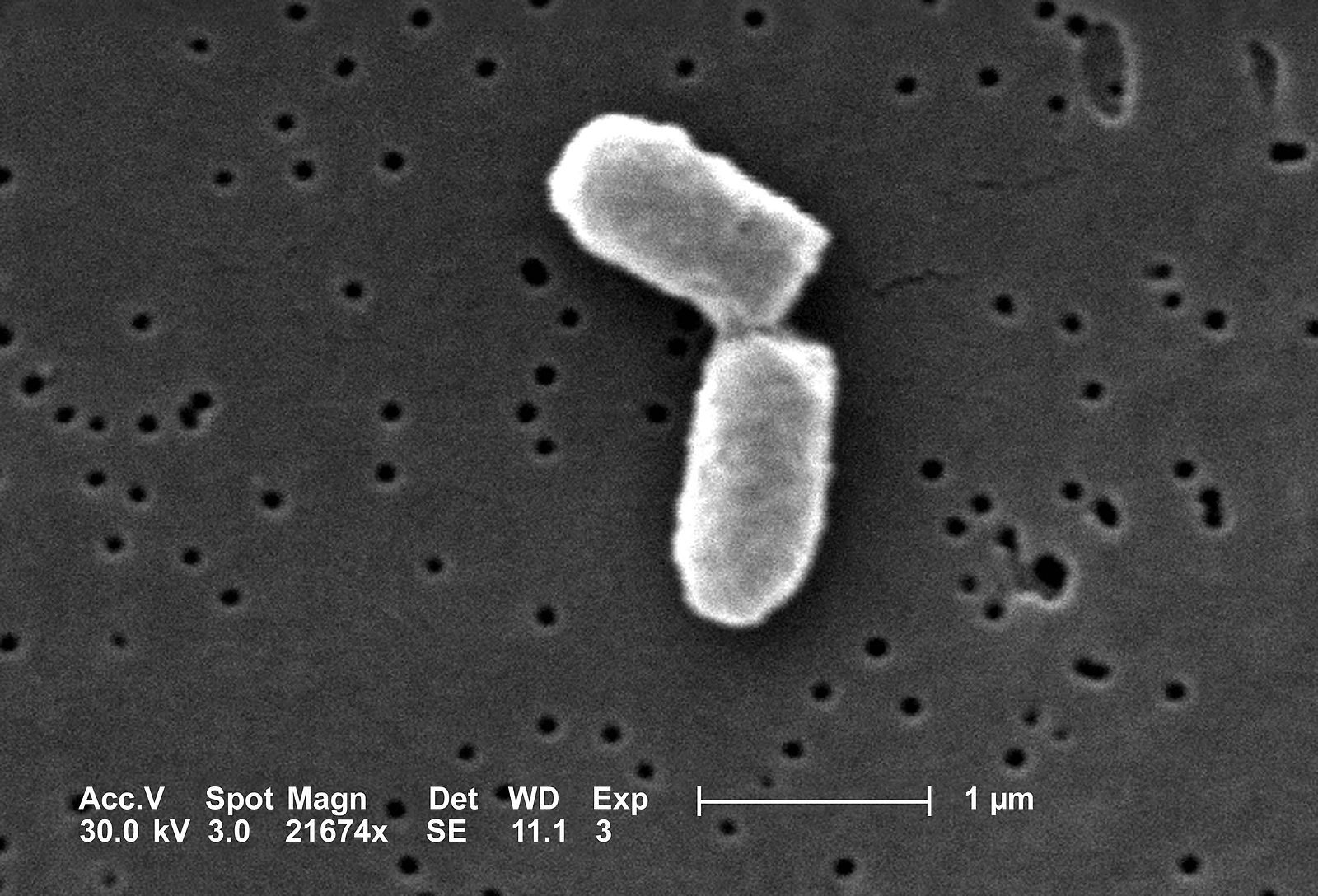

Most bacteria reproduce through a process called binary fission, which is basically just splitting in half. A mother bacterium will double in size, and then divide itself into two daughters, each of which contains everything she needs to make it on her own. This cycle of growth and division continues ad infinitum, until that formerly empty-looking petri dish (or lung, or piece of raw chicken) is splotched with colonies.

If this sounds a bit like an assembly line, scientists used to think so, too. “Ten years ago, we were all taught that the daughters were identical,” says Chao. “But what people have found recently is that’s not the case.” Instead, bacteria mothers divide unevenly on purpose in order to give half of their kids a head start.

A happy E. coli family. (Photo: Geralt/Pixabay)

Like most things knocking around this dangerous universe, bacteria accumulate wear and tear. Damages from sunlight, motion, and just plain living build up in a mother bacterium’s molecules, slowing her down. When it comes time for her to double and divide, though, she duplicates all this old cellular equipment, creating a fresh set that works like new.

At this point, the mother bacterium could split the old and new gear 50/50, dividing it into two identical daughters, Chao says. But instead, she takes sides just a little bit. Chao and his team found that your average mother bacterium gives one of her daughters 52 percent good stuff and 48 percent old stuff, leaving the other with 48 percent good stuff and 52 percent old stuff.

This amounts to playing favorites on a micro-scale. “The daughter that gets less damage gets a fresher start in life,” Chao says—it’s more likely to survive and divide a bunch, producing a longer, stronger, virtually immortal lineage. The one that gets more damage is effectively born older, and thus will die out a little faster, paying the price for her sister’s good luck.

An E. coli mother cell, dividing into two almost-identical daughters. (Image: CDC/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Evolutionarily, this “works like portfolio diversification,” Chao says. The fair and balanced bacterium mom who parcels out everything equally may, metaphorically, sleep better at night—but the savvy bacterium mom who spreads out her investments asymmetrically will end up with more grandchildren overall, a winning Darwinian strategy.

Chao’s lab, which last published on this phenomenon in 2011, is currently working on tracing asymmetrical damage distribution through more generations, as well as figuring out the mechanism that drives it. Mother bacteria “can either take the damage and put it in one daughter,” he explains, or “take the undamaged molecules and give it to the other daughter.” The second strategy is easier, he adds, but he’s not yet sure which is really going on.

As if this weren’t enough, Chao adds that this system of aging control is just a less advanced version of what, say, humans do. Sexual reproduction essentially eliminates the need to give new generations (molecular) damage at all, by making sure that all the stuff they’re made of is brand new. “The reason that our parents age is that they kept all the damage and protected us, the children,” he says. “Your mother’s aging is the price she paid to give you a fresh start.”

Happy Friday, you multicellular collection of ever-increasing damage. Now go call your mom.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook