The Dramatically Different World of ’70s Dating Ads

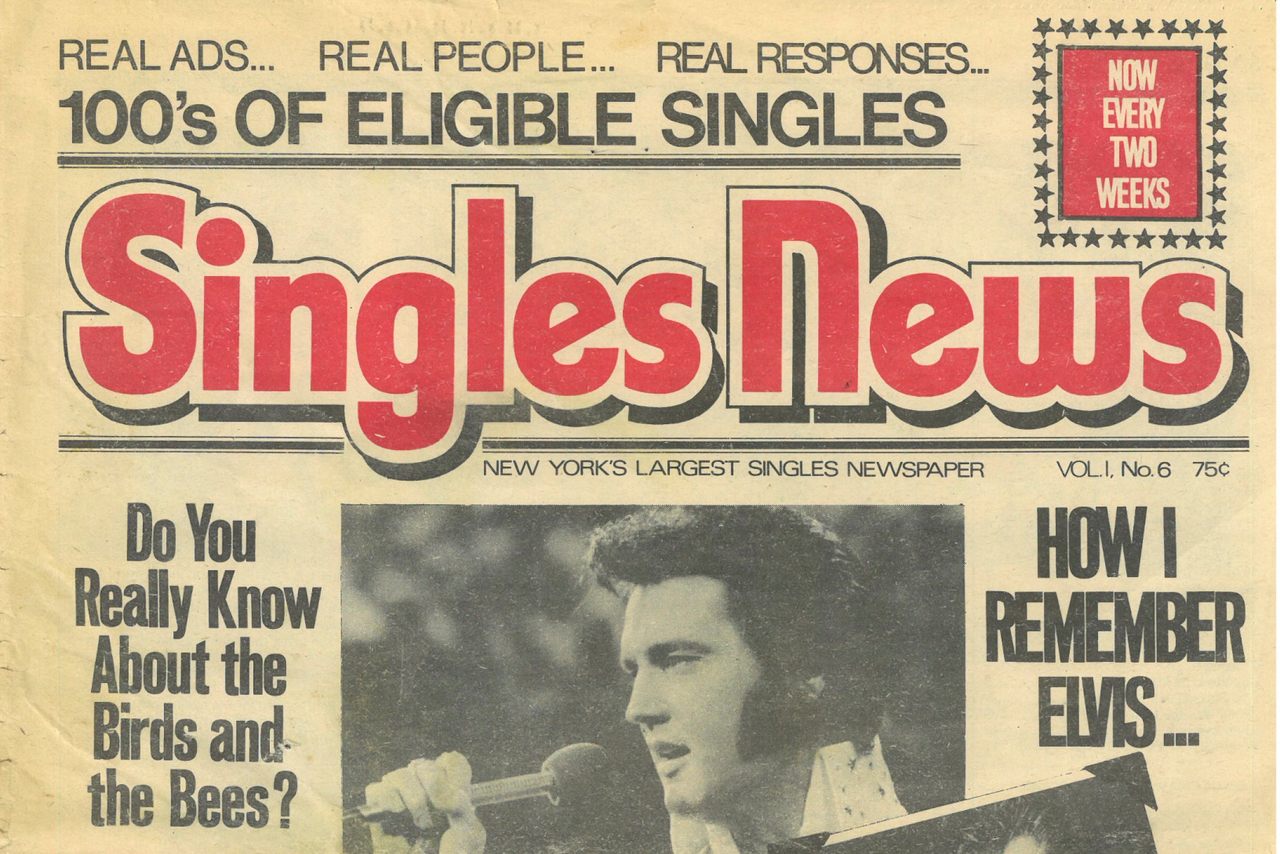

Before Tinder, there was “Singles News.”

The year was 1975, and a 31-year-old Marilyn J. Appleberg had been headhunted from a job in publishing to become the editor of a publication that would soon be known as Singles News. It was her first day, and she wore suede pants and a ribbed turtleneck. She walked in and was introduced to the owners of the small press that put out the paper, all men. One of them came up to her, she recalls, put out his hand, and said, “Per-‘suede’ me.” Now nearly 74 and still quite glamorous, Appleberg says, “I was extremely … curvaceous, so there were assumptions made. And then I turned out to be a romantic.”

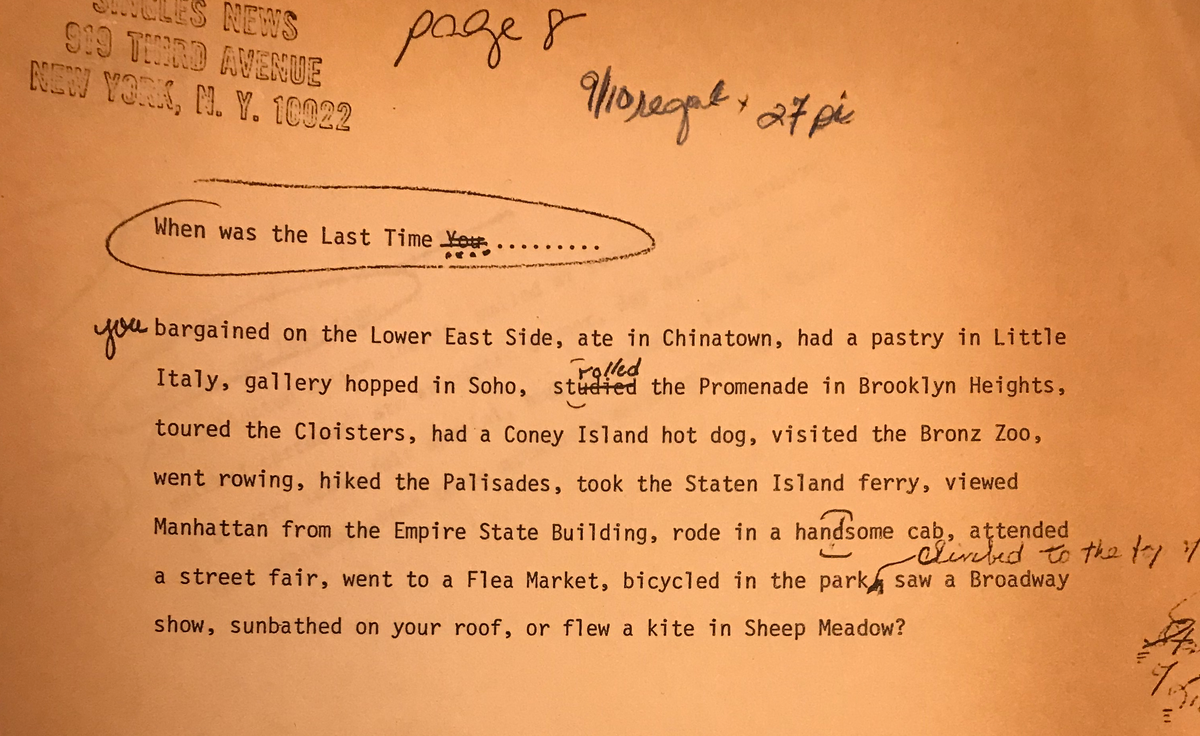

For the next three years, Appleberg edited the paper alone, under the intentionally gender-ambiguous moniker “MJ Appleberg.” Her résumé from the period, kept in a locker in the East Village co-op she has lived in since 1969, describes her as “responsible for editorial concept of pioneer monthly Singles News, geared to the interests of unmarried New Yorkers.” Appleberg found contributors, wrote much of the content herself, supervised the graphic design, oversaw sales, distribution, typesetting, photo sources, printers, and more. Thinking back on it today, she laughs, “I wonder how much they were paying me for that.” All this she did alone in an office building on 3rd Avenue and East 55th Street. The masthead on old copies lists just a P.O. Box, “in case someone wanted to sue.”

In the first half of the 20th century, you might marry your childhood sweetheart, the child of your father’s business partner, or a nice boy or girl you met at church or synagogue. Now, more than a fifth of couples meets online. In the meantime, after the pill “liberated” women in 1960, dating had evolved. By the 1970s, couples were meeting at singles bars or discos—or by putting personal ads in physical, printed papers. (That spirit of optimism and belief in serendipity similarly suffuses online dating. At least at first.)

But before Singles News launched in New York, the options for romantic personal ads in the city were limited, Appleberg says. “The Village Voice had kind of a kinky and or bohemian feeling, the New York Review of Books was more intellectual, bookish, so I think there was this idea, that we would be somewhere in between.” One German-Israeli-American “executive” in his early 50s sought a woman who was “lively, buxom, flexible, non-intellectual.” That was their target audience.

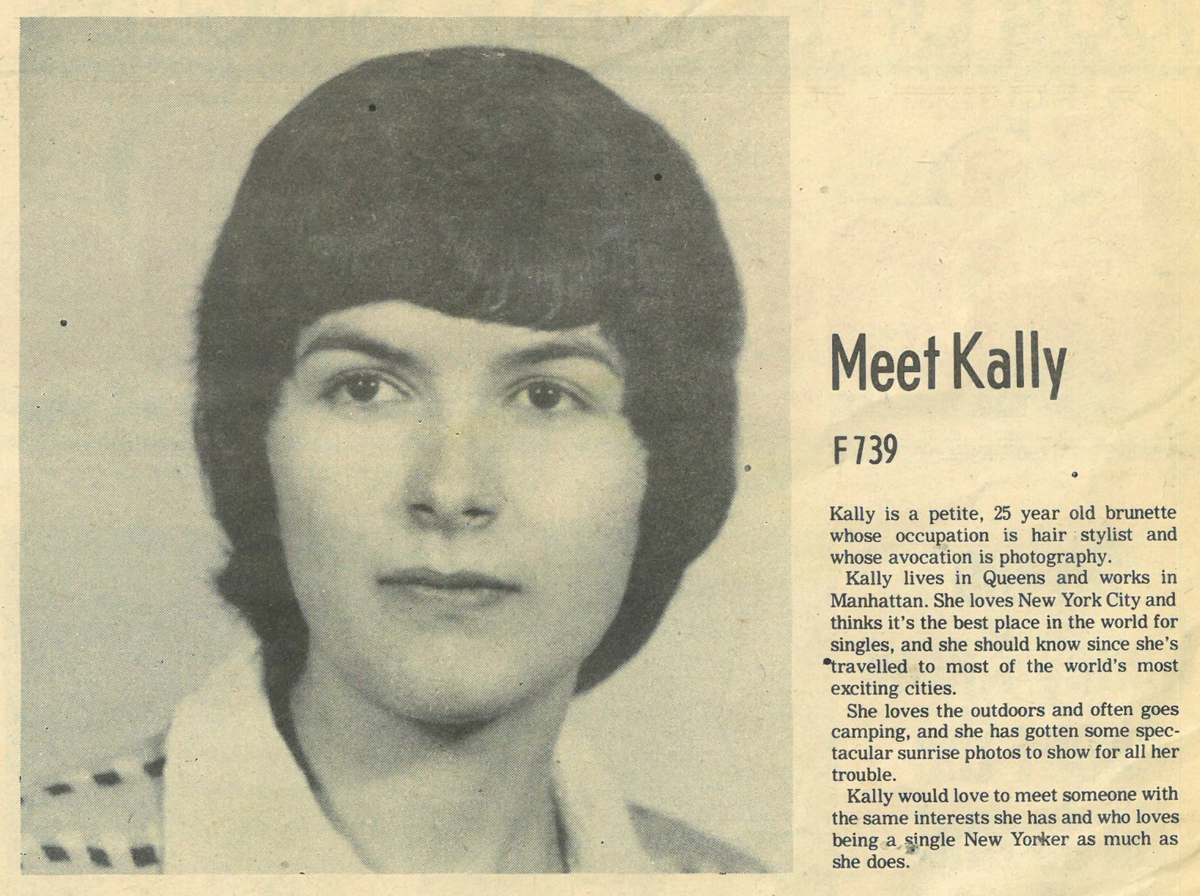

Singles News was the first, and largest, “singles newspaper” in the city, and promised “real ads… real people… real responses…” from “100’s of eligible singles.” A fresh romantic life could be yours for just 75 cents a copy. Across the country, comparable publications sprung up like mushrooms, eager to capitalize on a wave of singles and divorcees looking for love in a time of increased sexual openness. One such of these copycats on the West Coast, the Singles News Register, was the subject of a 1977 psychology journal article, “Courtship American Style: Newspaper Ads,” which attempted a deep dive on what it called “a fascinating new development in the field of courtship and marriage.” Coastal differences and similar names aside, the two papers were remarkably alike, and provide a revealing window into heterosexual dating at the time.

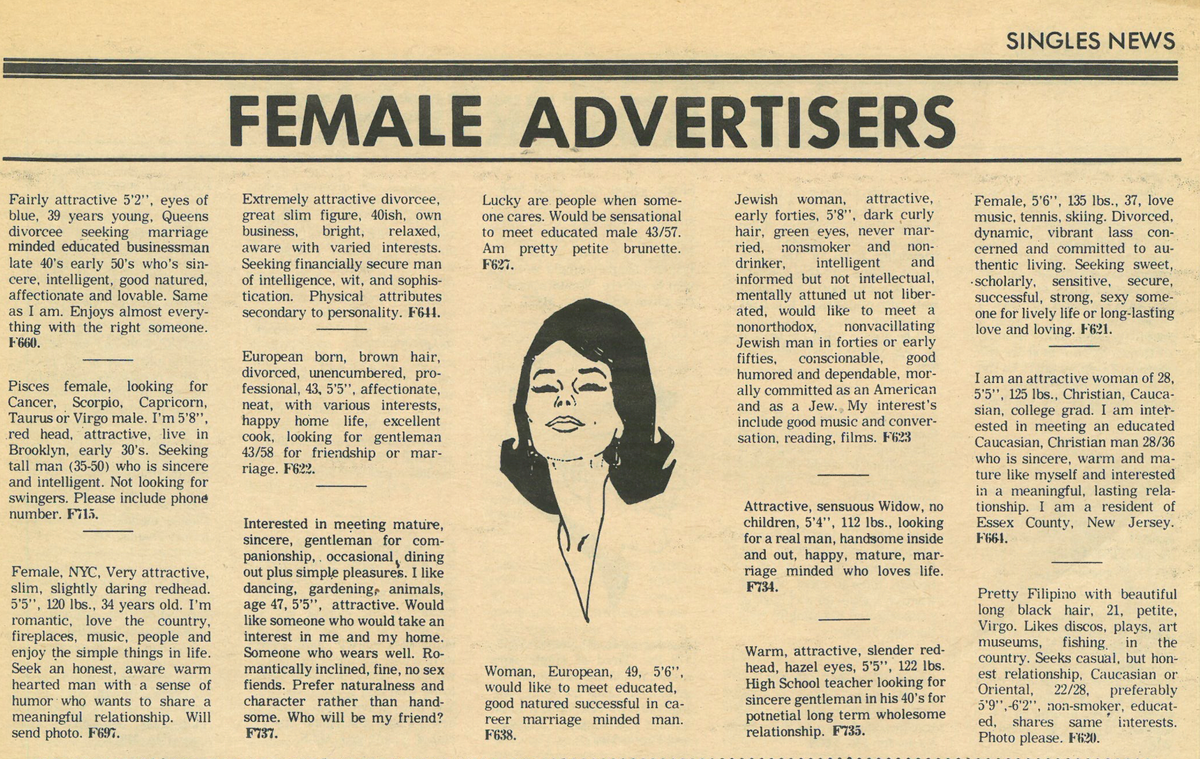

Shortly before the release of the first issue, Appleberg placed two “dummy ads” in the Village Voice to get a sense of who her customers were likely to be. The text of each was similar, though one claimed to be from a woman in her 20s, the other in her 40s. “There were about 25 or 30 responses to the 40s ad,” she says, “but there were over 200 to the 20s one, including doctors, lawyers, and several from prison.” In her paper, men’s ads skewed a little older, women’s slightly younger. Many of the seekers were divorced, and looking for an alternative to the carousel of what the authors of “Courtship American Style” call “the tedious and meaningless … round of bars and singles’ clubs.” One ad says the writer is looking for “a little fun and excitement and a lot of deep down feeling but not wedding bliss (I’ve gone that route).”

“The ads in this paper read a little like the ask-bid columns of the New York Stock Exchange,” wrote those authors, Catherine Cameron, Stuart Oskamp, and William Sparks. “Potential partners seek to strike bargains which maximize their rewards in the exchange of assets.” Positive descriptors about appearance abound. Men are good-looking, handsome, and sophisticated. Women are attractive, very attractive, or extremely attractive. Women stress those physical attributes, while men speak of status, occupation, or financial security. Cameron, Oskamp, and Sparks remark, drily, “The overwhelmingly positive content of the ads is especially clear if one considers the likely nature of information which was not presented.”

Well, hope springs eternal. One man searched for a “mature Twiggy-type woman who is also unpretentious,” while another wanted an “Angie Dickinson type.” Women were usually less specific: someone “warm, self-confident, with it,” though taller men were preferred. (Correspondingly, the men seem to have fudged a little—many listed their height as at least one inch above the average.).

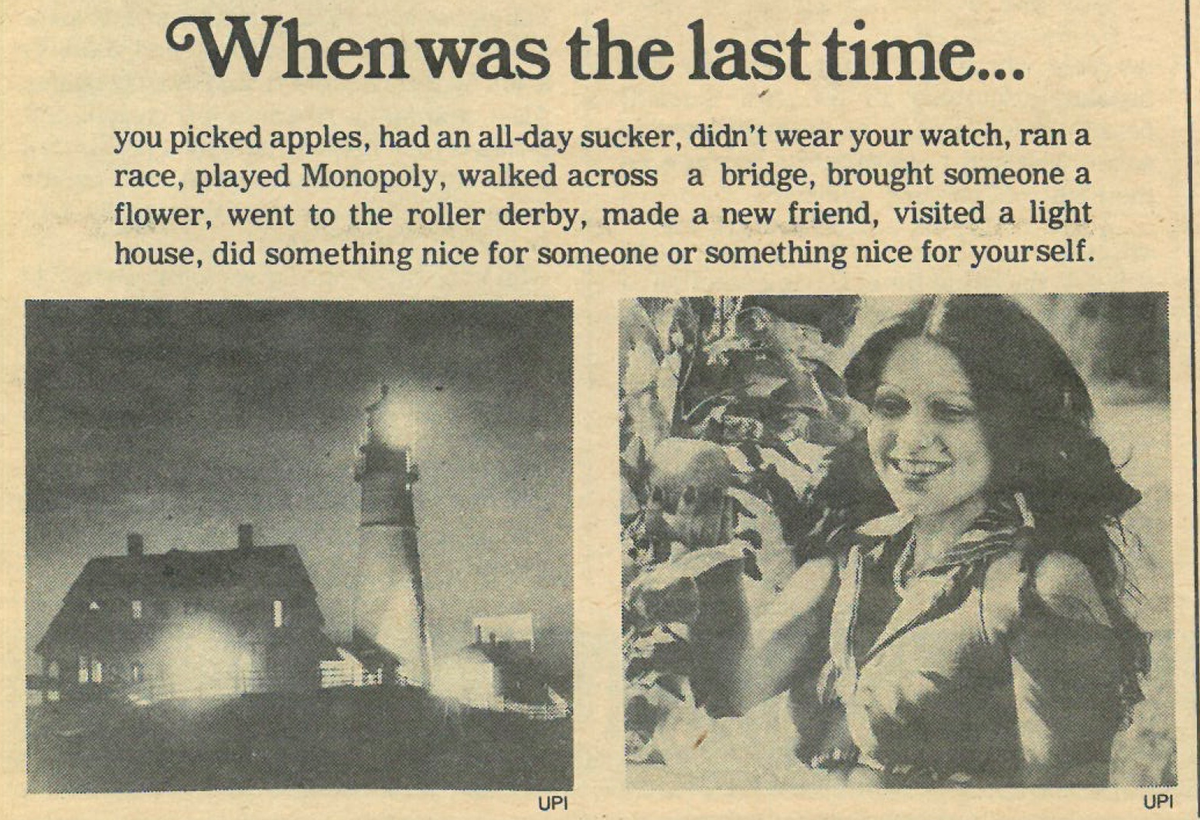

The paper, Appleberg says, was fashioned after an English singles magazine. Her bosses “didn’t care anything about editorial content, it was all about the ads and the money they were going to make from them.” Indeed, if they’d been able to run the paper without any articles at all, she’s certain they would have. Instead, the paper offered dating advice that is a relic of a time before the internet, when people were advised, to maximize the potential for romance on a Staten Island ferry ride, to “Check a daily paper to find out what time the sun will set on the day you want to go—that’s the most exquisite time for boating with a date.” Another article proposes “[getting] yourself a small fondue set, if you don’t already have one,” leaning heavily into the spirit of the decade.

Throughout those years, and for most of her life, Appleberg has been a prolific dater. Though she is agnostic about how she found those dates, she never placed an ad in the paper. “It seems like the dark ages compared to how people meet now,” she says. “Everyone was liberated, but not quite like now. The pill really changed things.”

At every party, she says, at least one joint was floating around. “You never knew where the drug came from, whose lips were on that before you, you never even thought about that stuff. In a strange way, it was a very innocent decade of time,” she says. “Once you were on birth control, you thought there was nothing to worry about. People having unprotected sex, things that I did when I was in Europe … ”

Her dating life from that period found its way into the paper. A bad boyfriend, who gave her a Dandie Dinmont terrier as a Christmas present, is immortalized in print. “If your lover wants to buy you a pet, opt for a bathrobe instead—it will hardly become a bone of contention if and when your relationship winds down and out.” The man didn’t stick, but the dog, Elizabeth, did. She’s now on Nick, her fourth companion of the breed, who caterwauls with joy as he hears her climbing the stairs. Her enduring love of vintage clothing—a 1950s navy-and-red checked coat, for example—appears in the paper, as well, when she recommends second-hand clothing stores as a dating idea. In each biweekly paper, Appleberg wrote a column called “When was the last time,” which asked readers to think back to when they last picked apples, or didn’t wear a watch, or visited a lighthouse.

The paper never made quite enough money, despite Appleberg’s best efforts. “I was a looker in those days, and sometimes I intentionally used it with newsstand operators,” she says, “to get them to put the paper forward.” In 1977, it folded, and she went to work for Moviegoer, an early movie listings paper owned by the same company.

Appleberg went on to write a series of travel books. Despite proposals from nine separate men, she says, she never married or had children, and has no regrets about a life spent traveling, collecting vintage clothing, and dabbling in real estate. (Though she does regret passing on an additional apartment in her building when it was listed at $125,000—it’s now worth $940,000.) One of her books, Romantic New York, built on her experience at the paper—and in life.

Although she says she hasn’t had a date in a while, many of her recent beaux have been much younger. “I’m too old for the old guys,” she says. She has no intention of slowing down, but she finds the idea of online dating “terrifying” and unromantic. She bemoans that beautiful women now might go unnoticed on the streets of New York, as everyone is nose-deep in an electronic world (though many women in the city probably disagree). So, today, when people ask her whether she would like to meet someone, she knows what she wants. It happened to her in Paris, Venice, and “everywhere I ever went.”

“I want someone to fall in love with me as I’m crossing the street. I’ll do the rest. I’m willing to do all the rest.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook