What Happened to ‘The Most Liberated Woman in America’?

Barbara Williamson co-founded one of the most famous radical sex experiments of the 1970s. Then she got wild.

(All illustrations: Michael Tunk)

I am standing in the living room of a wood-paneled modular house out in the Nevada desert. Alongside me is Barbara Williamson, once called “the most liberated woman in America”; and slinking toward us, across the grayed-out carpeting, is a large, muscular, wild animal.

Now 78, Barbara had driven me here in a massive red pickup. The plan was to make tea and have a good talk in her office (just past the meditation room). But first, she wanted to introduce me to someone.

“Are you ready?” she asked.

Sure.

I followed Barbara through the kitchen.

“Peggy Sue,” she called out gently. “Are you awake? Peggy Sue…”

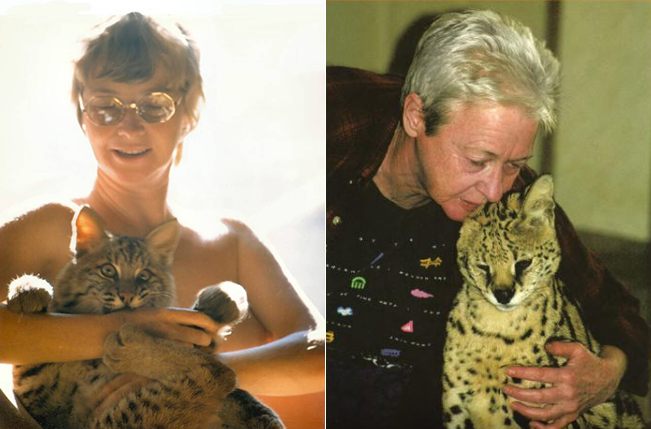

We turned the corner into the living room, and that’s when I saw her. Her eyes are huge and almond-shaped, her ears point upwards (a signature of the breed), and her paws are striking in their size. Peggy Sue is a Siberian lynx, over 60 pounds, with powerful legs and sharp, two-inch-long canine teeth. She has not been de-clawed. I’d been aware of this fact, but only in this moment does it truly register: Barbara shares her home with what is, more or less, a small tiger.

“I wanted the wildness,” Barbara says. “I have a streak in me that just has a lot of wild desires, and it makes me feel really good to be accepted by a wild animal—I don’t know for what reasons. Back to the old motto: ‘If it feels good, do it!’

Barbara, with her close-cut, bright-white hair and fuchsia lipstick, in light blue jeans and an ’80s-graphic parachute jacket, strokes the thick fur on the animal’s back and invites me to do the same. As we stand closer, each of us stroking Peggy Sue’s flanks, Barbara tells me they sleep together in the bed at night, sometimes curled up around one another.

Nearer now, the lynx looks a little raggedy, her skin a little loose, her long tail capped with two strange clumps of fur. She recently turned 20 years old—that’s how long ago Barbara retired to the small desert town of Fallon, Nevada, with her husband John. Out here on their 10-acre plot, the two created a spontaneous, guerilla-style sanctuary for “big cats”. Gradually, though, the creatures died of old age: three cougars, four bobcats, two tigers, two Barbary lions, a serval, two lynxes—and finally, three years and one month ago (Barbara keeps count), John himself. And now Barbara lives alone, with a single exotic animal, elderly herself, as her closest companion.

The lynx butts its head up against my legs.

“That’s a love gesture,” Barbara says.

The enormous cat does it again—two, three, four more times. I can feel the size and weight of her skull as she pushes me.

I’m aware that the affection she gives she can take away in a second.

How to Be Free

Barbara Williamson has built multiple sanctuaries around her wild desires.

She and her husband created perhaps the most legendary (and notorious) of the 1970s lifestyle experiments, the nexus of primal behavior and bourgeois America: the Sandstone Foundation for Community Systems Research. Founded in 1969, hidden high up in Los Angeles’s Topanga Canyon, Sandstone Retreat (as everyone called it) was a nudist community that promoted personal freedom through open marriage and group-sex parties. During its seven-year run, it attracted about 500 members and 8,000 visitors, was featured across national media, played a central role in a bestselling book by Gay Talese, and became cultural shorthand for both the promise and peril of the Sexual Revolution. And always, at the core of this alternate universe, were the Williamsons.

Marriage in America has clearly been shifting shape in the decades since the ’70s: “polyamory” has developed into a movement, gay couples across the country can now legally wed, and an unprecedented number of women have chosen to remain single into their 30s and beyond. But there was no visible movement, no pushback against the mainstream, when Barbara was growing up.

Barbara Cramer was born in 1939 on a farm near Chamois, Missouri, to parents who were utterly indifferent. “My abuse came in the form of neglect,” she says. In her memoir Free Love and the Sexual Revolution: Finding Yourself by Removing Sexual Boundaries, self-published last year, Barbara writes of her childhood:

There was never any hugging or touching or kisses. I’m sure I wasn’t even rocked as a baby…I never thought of my house as a home. It was just a silent, cold building where I slept. When I lay in bed at night, my brain churned with questions: Who am I? Why am I here? Why doesn’t anyone talk to me, touch me, or love me? Why am I so unlovable and alone?

She grew up isolated from urban life and culture—with the exception of one film that she watched in 1958, at the age of 18, at the local movie house, Auntie Mame. The film stars Rosalind Russell as an eccentric grand dame who rescues her nephew from a life of convention. At one point, Auntie Mame (Russell) shouts out from the top of a sweeping staircase: “Live—that’s the message! Yes, live! Life is a banquet, and most poor suckers are starving to death!”

It was burned into young Barbara’s memory.

Barbara with Doug and John. (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Williamson)

Barbara didn’t want the unexamined life of her parents (and everyone she knew in Missouri). She didn’t have any particular interest in getting married or having children—she wanted pleasure! Besides, she couldn’t imagine life as the appendage of a man. “I saw them as selfish, aggressive, narcissistic, arrogant, and unfeeling,” she writes. “Why in the world would I want a dolt like that hanging around and contaminating my environment? No thanks. I would make it on my own.” After graduating from high school, she took the money she’d saved from working at the local dance hall and, in lieu of college, soon made her way out to Los Angeles to find a job.

She managed to land work at New York Life Insurance, and discovered that she had a natural talent for sales. By the age of 22, in the early ’60s, she was earning in the high five figures. (“Word was out: Don’t fuck with Barbara Cramer!”) A self-described Meg Ryan type, she owned a slick new Ford convertible, rented a house with a pool, and spent many of her weekends water-skiing with girlfriends and their revolving roster of dates. She had no desire to choose a mate.

Until she met John Williamson. He was a prospective client (at the time, the former Lockheed Martin engineer was managing a small electronics firm in the Valley), but Barbara quickly realized their relationship would run deeper than that. He spoke in a thoughtful, melodic voice, and he was the first man she’d ever met who was a talented listener. Their first date, at the Hollywood Hills Hotel, transformed into a spontaneous weekend in San Francisco, packed with long conversations about what they wanted for themselves (John was also uninterested in a conventional life), and culminated in “simultaneous orgasm.” Within days, Barbara moved in; within a month, they were married—to make things easier on Barbara (after all, the sexual revolution hadn’t happened yet, and living in sin brought social shame).

Barbara and John’s passport photos, c. 1969. (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Williamson)

But they didn’t plan on playing out some Middle American fantasy of “husband and wife.” They could be frank with each other about anything—and that’s just what they did. Over the coming years, the two began wondering aloud what their ideal lifestyle might look like, free from social constraint. Both came from very little (John had grown up in a dirt-floor cabin in Alabama swampland) and transformed themselves into high-earning young professionals—but now they questioned their values. What if, in lieu of brand-name clothes, they just went naked? What if, instead of indulging in possessive relationships, they allowed each other to have sexual experiences with other people whenever either of them felt the urge? As long as they remained honest, they agreed, it wouldn’t have to affect their love for one another. On the contrary, they decided, the key to staying together was to take the pressure off their marriage in this way. “We felt it was impossible for one man and one woman to fulfill all of each other’s needs.” It also helped that John embraced Barbara’s new awareness of her bisexuality.

By the late ’60s, they began inviting open-minded friends and couples to join them at their house on L.A.’s Mulholland Drive for evening sessions of group nudity and partner-swapping. A few of their guests even moved in. The counterculture movement had begun to take shape, especially on the West Coast, and with it came the idea of communal living—in slightly gross, hippie conditions, sometimes without electricity or running water, crashing in sleeping bags, the inhabitants wearing Goodwill clothes and depending on handouts and the occasional panhandling. But the Williamsons had worked hard to become solidly middle-class, and now nearing 30 and 40 respectively (i.e. pretty much “dead” to the hippie generation), they decided to invite into their circle only similarly driven, “upscale” people who shared “America’s traditional values”—with less traditional views, of course, about marriage and sex. About 10 people gathered in the living room nearly every night, sipping wine in the nude, massaging one another, occasionally retiring to one of the bedrooms for sex with a friend’s partner while the group consoled the un-coupled spouses. For newcomers, the first night could be hard, stirring up complicated emotions.

But as their Mulholland Drive experiment carried on, Barbara and John grew bored with its limitations: so many of their guests would simply come to swing and then immediately return to their daily lives, otherwise unchanged. They wanted to build something more radical and transformative.

“What if we started a commune,” Barbara writes, “a grown-up one built with comfort and ease in mind where everything was beautiful and well- kept, with a big, luxurious home that would comfortably hold as many guests as we wanted to join us. We envisioned lovely furniture, soft lighting, beautifully manicured lawns, well-tended grounds, and a clean, well-stocked kitchen with all the amenities of a perfect civilization.” They could live in total honesty and open sexuality, free from jealousy. And they would do it with enough material comforts to make even Rosalind Russell feel at home.

Californication

In 1968, John sold his share in his corporation, and he and Barbara used that money (over $1 million today) as the down payment for their “perfect civilization,” their New Sexual Utopia. They soon found the ideal property: 15 secluded acres way up a winding dirt road in Topanga Canyon, close to Malibu and just far enough from the city. (The Monkees had tried to purchase the place, but the deal fell through.) With a multi-bedroom main house, two guest cottages, and a separate structure that contained an Olympic-size swimming pool, this was the bourgeois free-love compound they’d been dreaming of.

The couple set about engineering the right mood. Barbara decorated the 60-foot-long living room on the main floor with plush carpeting, velvet sofas, a crystal chandelier, giant ferns, and floor-to-ceiling curtains—everything in natural tones, everything designed to feel good on naked skin, and only the most flattering lighting. In the large basement, complete with massive fireplace, they covered the floor with a collection of mattresses and waterbeds. They christened this space the “ballroom”—you know, for balling. And in the final stroke in their return to nature, the Williamsons removed all the doors, converting the bathroom on the main level into a kind of thoroughfare. “There was no backstage at Sandstone,” Barbara writes. “Whatever anyone did was done openly in front of everyone else. I always felt that constant exposure made it virtually impossible to be dishonest.”

By October of 1969, they were ready for their first party. That evening, as people began trickling in, Barbara says she and John were anxious: “We took all our clothes off, went down there, holding onto one another, and just watched.” But they’d miscalculated: Unsure of how to attract guests, they’d encouraged a friend to invite “the Playboy bunch”—some of the folks who usually populated Hugh Hefner’s parties—and the results were far from what the Williamsons had envisioned.

Sandstone Retreat. (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Williamson)

It’s not hard to imagine what happened next. The men, used to swinging at the Playboy Mansion, worked their way through the women at an impressive pace. “It was as if it was fine for the women to be abused by the guys,” Barbara says. “I saw this one woman—she never got up all night! She must have been fucked by 10 guys. And I thought, ‘This is really an abuse of beauty. This crowd does not share our values whatsoever.’” Sandstone was not meant to be some trendy “fuck club.”

So they called a do-over, and spent time strategizing: how to attract a crowd that did share their values? They ran ads for membership in the Los Angeles Free Press and rented an office in Westwood where they could meet with any couples that might apply (a way to keep “freaks” from knocking on their door). These interviews often closed with a critical question: “So, just how much do you love one another?” Some had met only days before; others had been married for 20 years—what mattered was how close they were, how committed to the relationship, and how ready to test it. Those people made the best Sandstone material: they created more of a balance, temperamentally, as well as a balance between the sexes. (In keeping with its friendliness to the middle class, sex at Sandstone seems to have remained all about the heteros, with a handful of bisexual women in the mix but no men openly interested in men.) Most importantly, the Williamsons thought, they had to keep the place from becoming a den for randy single guys. There was also a less high-minded qualification for joining the nudist, group-sex community: preference went to people who were in good physical shape. (Ironically, this left John Williamson himself as one of the only members with a potbelly.)

They ultimately developed a core group of about a dozen live-in members who managed the community full-time, in the nude, opening the doors to vetted visitors six days a week, with ballroom sex parties every Friday and Saturday. This inner crew was comprised of a fluctuating collection of one-on-one marriages and ménages-à-trois. As far as the part-timers, who eventually numbered about 500, they included people from a whole range of backgrounds—nurses, executives, professors, actors, musicians, artists, a pair of young Mormons, even a judge—and most of them mingled wearing nothing more than their eyeglasses or charm bracelets. Barbara writes of the power of nudity:

Once you took off your clothes and got real, everyone knew who you were and loved you for it. You were no longer hiding behind a layer of expensive clothing that showed the world how wealthy and hip you were. No low-slung, hip-riding bell bottoms and tie-dyed T-shirts proclaimed your disdain of the establishment. No military or law-enforcement uniforms declared your allegiance. No thousand-dollar Armani suits or five-hundred-dollar calfskin attaché cases advertised your status as a high-powered banker or attorney. When you shed your public persona and stand naked with a group of other naked people, incredible lightness washes over you. All pretense and game-playing are gone.

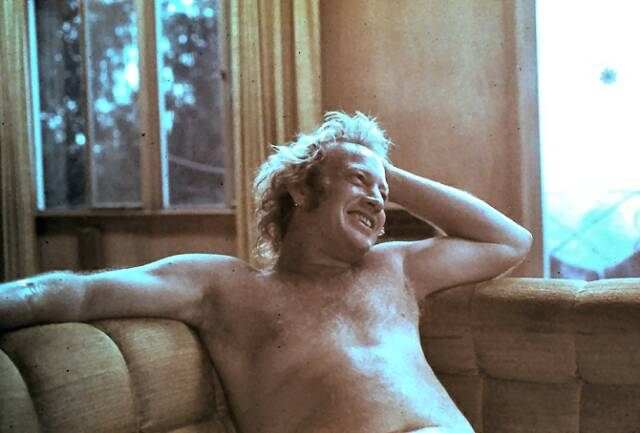

Overseeing it all, setting the tone, were the Williamsons, themselves naked at all times (save when it was their turn to go shopping for groceries). To many, Barbara was the boss, drawing up lists of chores and serving as a no-nonsense bouncer on party nights; while John was the unlikely sex guru, a big ape with curls of child-blonde hair and a soft, instantly intimate demeanor that made you want to lean in closer when he spoke, dragging on a cigarette between trippy conversational riffs.

John Williamson in 1972, during the filming of the Sandstone movie. (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Williamson)

Sandstone was intended as a “therapeutic environment,” promoting (in John’s words) “honesty, sharing, and freedom from bullshit.” They were also promoting open sexuality—“but in a very relaxed, low-key sort of way.” Anyone aggressive, competitive, or sexually pushy was immediately asked to leave. The Williamsons liked to reference the “Gestalt prayer” by Fritz Perls, a founder of Gestalt therapy:

I do my thing and you do your thing.

I am not in this world to live up to your expectations,

and you are not in this world to live up to mine.

You are you and I am I,

and if by chance we find each other, it’s beautiful.

If not, it can’t be helped.

If only it were that easy. Martin Zitter, who became the retreat’s press liason, remembers grappling with “a sense of separation or loss” from his wife Meg as each witnessed the other experimenting in the ballroom. It was challenging to be confronted with your partner having sex with another person—Barbara herself says that the pain of those possessive feelings toward her own husband never completely went away—but it was intended to be difficult. The goal was to separate the idea of sexual exclusivity from love, and tearing off that Band-Aid hurt.

In a surprise to their partners, the women proved more resilient than the men. Jonathan Dana and his then-wife Bunny co-directed a 1975 documentary called Sandstone, living on the grounds, in full participation, in order to do so. (A Dartmouth grad who’d married at 23, Jonathan was taking time off from earning a business masters when he began his foray into filmmaking.) “The people you thought would have the easy time might have the harder time: guys bringing their wives and then discovering that they can’t handle their wives being there,” he says, “The women were ready to break out—and they had a support network from the other women there. The guys were kind of by themselves; they were still male-competitive—but the women would find themselves in demand and very nurtured.” Or in Barbara’s words: “Most of the women took to Sandstone like a duck to water!”

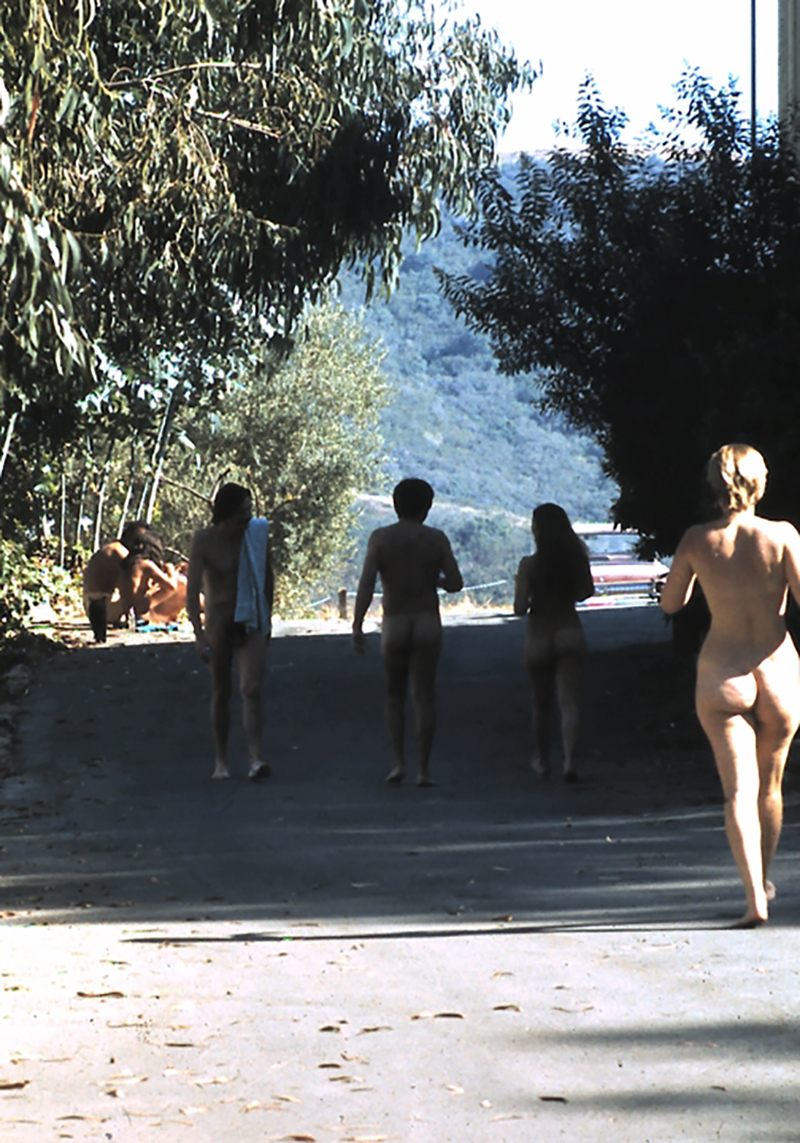

On the grounds of Sandstone. (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Williamson)

Though Sandstone was not the only space in late-’60s and ’70s America dedicated to sexual freedom—the West Coast was dotted with “free love” communes and cults—it was the cushiest and most middle-class-relatable. The scene, captured in the Danas’ doc, is striking for its banality as much as its graphic sex. Sipping red wine and dining on an elaborate buffet, members and guests—ranging from their 20s to 50s, most of them in the nude—talk about home renovations, going shopping with their mother-in-law, favorite vegetable dishes, and studying for summer school. (The Danas also documented where the evening goes from there, with everyone descending into the red-light “ballroom,” piling onto the mattresses, a tangle of bodies.)

Sandstone was also the most self-promoting of the California communes. Barbara says that she and John occasionally made the trip down to UCLA to give guest lectures on sexuality and human psychology. Sammy Davis Jr. and Bobby Darin to Berry Gordy and Peter Lawford attended Sandstone’s parties. The community was covered by Rolling Stone (with the headline “Sensuality Comes to the Suburbs”), the Los Angeles Times (“Sandstone is not a ‘sex club’ or wife-swapping fraternity”), Penthouse (“sexual hang-ups are treated by permissive therapy or orgy”), and Regis Philbin’s morning talk show. And in what would ultimately become Sandstone’s major claim to fame, journalist Gay Talese spent months there as research for a book about sex in America. He spoke about the experience in interviews with Esquire, New York magazine, and The Tonight Show. “There’s a lot of touching and hugging and friendly kissing and the greatest feeling of camaraderie I’ve ever experienced!” he told Johnny Carson. “If you want to have sex, you simply take your chosen partner by the hand and lead them into the ballroom and have sex! It’s that simple.”

Radical honesty and open marriage had infiltrated Middle America, and Sandstone was at the center of the national conversation. In a screen moment that must have seemed prophetic, the Sandstone movie lands on an image of John Williamson naked on the lawn, his blonde hair backlit by the sun. “Five years from now,” he says, “it’ll be an entirely different world.”

‘A Sense of Wonder’

Or not.

In 1980, Talese published his book, Thy Neighbor’s Wife, with Sandstone as its centerpiece, and it became an instant bestseller (it earned $4 million before publication). But by that point, the place had been shuttered for half a decade.

Attracting members to the radical commune had always been a challenge—you were required to register under your legal name, which scared off those who only wanted to attend the occasional party anonymously—and the Williamsons felt obligated to keep dues low, at $240 per year. (“Much to our disgust,” Barbara writes, “everything is about money.”) Besides, Barbara and John, loners at heart, had gradually gotten burned out on constant community; after hosting thousands of visitors, they wanted some quiet. At the same time, a battle with the local zoning board, hostile to their sex-obsessed nudist neighbors, was draining their resources, and the bad vibes began to chase members away. Compounding the real-world problems plaguing their utopia, large swaths of Topanga were then declared national parkland, seriously reducing its resale value. To make a long, awkward story short, the Williamsons took off with what little money they had left, and a few members managed to keep Sandstone open for just another 18 months until it shuttered for good in 1975.

Even without the money-and-real-estate drama, the group-sex community would have shuttered for good with the horrific spread of AIDS in the early ’80s. And in a broader sense, the mood of the country had shifted, as a wave of divorces gave way to a generation of latchkey kids, unimpressed by their ex-hippie parents’ behavior (see: Family Ties’ Alex P. Keaton). Ronald Reagan was twice elected president on the strength of his return to “family” values. Sexual exploration, especially among married heteros, retreated behind closed doors. Communities dedicated to “free love” seemed hopelessly passé. And for the hundreds of thousands of readers of Thy Neighbor’s Wife, the story of Sandstone was that of the ’70s’ ultimate failed experiment.

Activities at Sandstone. (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Williamson)

It’s 11a.m. in New York City when I wake up Gay Talese. I’ve cold-called him on his ground line and to my amazement, being of another generation (he’s 84), he actually picks up the phone. At first, confused, he calls me by another woman’s name. He was up until five this morning, finalizing the text of a new book and dealing with a gaffe he’d made about women in journalism during a recent university appearance. Conscious of the clock, I ask him about the Williamsons.

“That was in a time when group sex and consensual adultery were kind of a new thing,” he says. “The big mission of John and Barbara Williamson was to try to make people feel that extramarital sex didn’t reflect a bad marriage—that you could have a central relationship and satellite relationships and not harm your partner.”

This ran counter to Talese’s entire upbringing—as a Catholic altar boy in the ’40s in Ocean City, New Jersey, and a college student in the ’50s. “When I had my first girlfriend, whatever sex we had was in a car, and you wouldn’t risk going to a motel. All that was so different”—he means Sandstone, and that entire era—“I wrote about it with a sense of wonder.” From massage parlors and X-rated theaters to pornography and swing clubs, Talese reported on the evolution of American sexual mores, in the role of “participating observer.” The book, while a great success, left him described in the press as a sort of pervert and nearly derailed his now 57-year-long marriage—something he’s discussed openly.

Like the Taleses, the Williamsons stayed together. I mention how counterintuitive I find it that a couple that founded a free-love commune would eventually retire to a tiny town, just the two of them, no longer that concerned about seeking out new partners. “You can’t do as easily at age 50 what you can at age 40,” Talese says. “That’s true of almost everybody. You get worn out—like you’re Michael Jordan one year, and then you’re not.”

At this point, he goes off track. “Why don’t you write a book?”

I tell him that I have written a book, published recently.

“But you didn’t answer my question: Why don’t you write a follow-up on this today? Why not?”

It’s a legitimate idea, if a little obvious in a media culture that, at this point, has picked over sex and sexuality seemingly from every angle. But my thoughts are cut short by his next question:

“How old are you—28?”

I’m well into my 30s.

“Are you married?”

No, but I have a partner.

“Woman partner or man partner?”

Man partner.

“Does he allow you to have sex outside of the relationship?”

That’s not something we’ve been doing…

“Oh, so you’re back in the 1950s. You’re not anything like the people I wrote about in this book, are you?”

I guess not. I mean, I’m liberal, but—

“I’m not chiding you!” He’s losing patience. “I’m just trying to get where you’re coming from.” He asks again: “Does your partner allow you to have sex outside of the relationship?”

That’s not something we’ve discussed.

“Well, then you can’t write this book.” He’s disappointed. “You’d have to be someone who could do that.”

The conversation ends shortly after that.

Coming Back to Earth

More than writing the next installment in the saga of Sex in America—which apparently would require the author to repeatedly take her clothes off—right now I’m curious about a narrower question: What happens after founding a radical, nudist, group-sex commune in the culture-shifting ’70s? When your life-transformative experimental utopia comes to an end, how do you continue with the rest of your life? Do you compartmentalize it, see it as one of a series of personal projects that weren’t built to last? Or does the experience color everything that comes afterward?

In other words, what is Sandstone’s legacy?

Most of the members, it seems, dissolved back into some semblance of mainstream life. Martin Zitter went on to work for Merrill Lynch. In 1988 he married a Japanese model and has been with her ever since; the two live together in Pasadena. “I went from being kind-of a beatnik, to kind-of a sex maniac, to being a stock broker.” But he still fantasizes about what they made happen in Topanga almost half a century ago. “I look at it like I look at the space program: We had a foot on the moon, and we had every ability to keep that foot there and make that place home and hospitable—and then we just stopped going.” If he had $10 million with which to build a splendid new property, he says, he’d do it again—create a new, more decadent Sandstone.

For filmmaker Jonathan Dana, his documentary was given an X-rating and released on the eve of Sandstone’s closing. It screened in theaters for 18 months, bringing in $1 million. But Dana himself never fully extricated himself from the Sandstone experience. “Afterward,” he says, “it was a strange transition. To go shopping for two people instead of 12, to be dealing in the regular world, where things we’d gotten accustomed to as normal were off the table—even just to go out to a party to meet people, it was a whole different thing. It was difficult.” To this day, when he’s alone in his house, he often goes naked. “Nothing about the theory of it—that’s just something I started doing there that stayed with me.”

He also left Sandstone with his relationship radically transformed. Shortly after filming ended, he and his wife moved in with another L.A. couple and entered a “group marriage.” It lasted a year before his wife decided she’d had enough—and then it became a “triad” that endured for nearly another decade. (When they published the memoir Beyond Open Marriage in 1979, the three of them appeared on The Phil Donahue Show.) “When we were in the flower of that day, so to speak, it was fashionable to be in an open relationship or a Sandstone-type environment,” he says. “That was an interesting time! The fact that there were three of us, going to parties—people thought we were kind of cool.” But sometime in the early ‘80s, the lifestyle went out of fashion. “The times moved on. And you could literally see the smoke on people’s asses as they ran away from us.” It was one thing to flaunt convention in a supportive, bohemian environment; it was another thing to face complete social rejection.

For his generation, catering to your libido had become less pressing—the Michael Jordans of the situation found their skills waning—and people were turning to material concerns, like the desire to “cocoon in a big fancy house.” “There’s always a regression to the mean,” Dana says. Since that triad dissolved, he hasn’t made another attempt at polyamory.

For Barbara and John, the catalyzing duo, their situation after Sandstone was more extreme. Beyond their undervalued property, they had very few possessions—and even fewer clothes, thanks to several years of nudism. They were like a pair of nuns ousted from the convent, ill-equipped to re-enter society. They’d kept a motor home on top of the hillside at Sandstone, and they now drove it north, to a piece of land they’d optioned across from Glacier National Park, in Montana. There they parked their home and stayed a while, recovering from the years of hosting, going back to their nights on Mulholland Drive.

Poolside at Sandstone. (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Williamson)

Uncertain of their future and in need of some kind of safety net, they decided to head all the way to John’s home state of Alabama—to Mobile, where he had a brother. This was of little help—John’s family ties proved thin. They realized, to their shared horror, that they could not simply step back into their previous life as high-earning professionals. They would not only have to rejoin the mainstream, but start over at a much lower rung on the corporate ladder. While this proved difficult for John—engineers in their 50s were not in demand—Barbara, ever resilient, was able to return to insurance sales. But it was awful:

…I was soon (and once again) sitting behind a desk dressed in a business suit and pantyhose. Ugh! Pantyhose! How I hated them. I was forced to buy a few outfits at Goodwill and other thrift stores, and I had to grit my teeth each morning when I put them on. It was unnatural, and I hated every minute I spent dressed in the working woman’s uniform!

They found themselves in a trailer park, subsisting almost entirely on bologna sandwiches on Wonder Bread, dreaming of the elaborate meals they were served at Sandstone. Every weeknight, Barbara would return to their trailer, peel off her uniform, and make the same dinner in a kitchen packed with large Southern cockroaches. One such evening, a “biblical vision” came to her—“of John and I, blissfully naked, relaxed on a soft bed of grass in the Garden of Eden, and then suddenly and violently cast into hell.”

To make matters worse, she was often far too tired for sex.

Eventually, after a few years of living in misery—and a few moves into marginally better housing—Barbara saved up enough money for them to return to California in 1983. This time, they headed not to Los Angeles but to San Jose, where she soon opened her own insurance company. They rented a house with a hot tub, and quickly discovered that a slew of 20-something women, high on the myth of Sandstone, were eager to come over and party on the weekends. “So it became all these girls and me and John!” Barbara says. The Williamsons might have been booted out of their experimental-lifestyle Eden, but they managed to sustain themselves with a swinging paradise of their own.

The Wild Cats

All of this brings us back to the 60-pound Siberian lynx.

Over the next 10 years, Barbara, then in her 50s, worked to make their retirement possible. She and John wanted to leave California, with its noise and trendiness and materialism, and buy a plot of land where they wouldn’t have to worry about their finances again. And so they headed to Fallon, Nevada, a town populated by retirees and young military (there’s a naval air station nearby), with a main street, 15 minutes from their house, defined by thrift stores, small casinos, and at least one combination-steakhouse-and-casino.

But in the middle of executing their plan, the urge struck to form another, markedly different commune, a new Eden: a sanctuary for massive, exotic cats.

Shortly after relocating to Fallon, John learned of a collection of “big cats” that were set for euthanization—they’d been seized by local authorities because of their owner’s negligence. If he wanted to intervene, he had 30 days in which to prove that he could house the animals himself. And so, while Barbara was still closing up shop in San Jose, he managed to build a large, fenced-in outdoor area behind their new house, complete with homemade kennels, for the three cougars, one lion, and one tiger. Over the course of the next several years, they went on adopting until they had a total of 14 cats.

Through the tigers and cougars and lions and lynxes, the Williamsons seemed to be resuming the project they’d begun decades earlier with a collection of humans. Of John and the cougars, Barbara says, “They were just on the same wavelength; they understood each other by looking into each others’ eyes. It was a perfect relationship.” She also remembers how John, on his first meeting with their male Bengal tiger, opened the animal’s mouth and stuck his entire head inside—then stepped back, patted the tiger’s shoulder, and walked away. The lynx Peggy Sue and a serval named Streaker were given free rein of their house, rough-housing with John during the day and piling into the couple’s bed at night. When they used the hot tub they installed between John’s office and the animals’ kennels, they’d allow their lion to roam free and play her favorite game: she loved to stand on the humans’ heads with her front leg, shoving them under the water.

They called Tiger Touch a “research facility”—but, as with Sandstone, it’s unclear what kind of specific scientific research was ever done here. In the ’70s, the Williamsons certainly launched a grand social experiment—but they were never scientists, never recorded data with any kind of methodology at all, nothing beyond the anecdotal.

In spite of John’s attempts at crafting mission statements and social-theory papers (his writings are tough to get through), the Williamsons were never great at articulating themselves, more in tune with the experiential than the verbal. For her memoir, Barbara hired a ghost writer, Nancy Bacon—the author of, among other titles, the ’70s tell-all Stars in My Eyes…Stars in My Bed. She used it to try to establish their legacy: rather than long-haired Haight-Ashbury types dropping out, she and John were a married professional couple redefining what marriage could be for the middle class—and in a well-appointed canyon estate. “We were really architects of change,” she says. “Change agents!” But there was a limit to what they were able to accomplish. There had been a financial barrier to sustaining their utopia—and Barbara admits to a more intimate, sexual hurdle as well: Her personal dream had been to form a triad with John and another woman, and that never panned out. Even at Sandstone, she says, “the women—at the end of the day, they all wanted their own man.” What, ultimately, is more essential to our nature: carnal freedom, or territoriality?

At one point, cruising in her red pickup, Barbara drives us past the spot where John is buried, not far from their house, in a “green” cemetery called the Gardens. She tells me about his final years: a series of strokes and seizures caused him to lose his memory in chunks as well as his ability to drive or even to think clearly. After a half-century-long relationship between two fiercely independent individuals, Barbara became John’s caretaker. She’d been caring for him for so long that, shortly before he passed away, he said to her, “I’m just slowing you down, aren’t I?” He was in and out of hospitals, until he was finally diagnosed with lung cancer. In the end, she felt a sense of relief when he died—it had been hard to watch such a free man decline so sharply. He’s buried here in a basket made of seaweed, his place marked by a rock engraved with his name; free from chemical embalming, his remains will eventually return to nature. A stone with Barbara’s name has been placed alongside his plot. “All it’s missing is a number.”

About 500 miles away, in Los Angeles, the former Sandstone property is now in the hands of a local real-estate family who, having given up on selling the place, have allowed the premises to fall into disrepair. The pool burned down a long time ago.

Creatures of Instinct

In her kitchen in Fallon, Barbara places a kettle on the range while Peggy Sue grows increasingly impatient with me. Barbara asks me to choose from the boxes of tea in the open cupboard—“Lemon ginger? Green? Chamomile?”—as the lynx has rounded the corner from the living room and is now trailing me from one counter to the next. She is making a sound that’s unmistakable, even to someone who has never before spent time with an exotic cat. A deep, low, insistent growl.

Barbara boils the water, and I move to stand by her side. The lynx follows me there too—stalks me, really—her growl stronger now, her teeth visible, her lips inches from my thighs.

And this is when I experience it: a real, primal-level terror. It’s a very distinct, rare feeling—while I’ve never had to prove myself on a battlefield, I’m fairly brave for a 108-pound woman. So I make myself breathe slowly, steadily, thinking that a raised heartbeat, added to the adrenaline coursing through my body, would be the worst message I could send to the large, fanged animal. My hearing changes, as if I’ve just gone underwater or into a tunnel.

“She’s acting different,” Barbara says. She wonders aloud if perhaps the cat is feeling possessive of her.

Barbara with a young lynx and a serval (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Williamson)

Barbara shoos the lynx away, but the animal does not listen. She shoos her again; again, no response. I think of how she had told me over the phone, lightheartedly, that the cat “doesn’t listen to me anymore”; how a friend who’s a Vietnam vet no longer visits her for fear of the cat; how the cat, since the disappearance of the house’s alpha male (John) has become far more temperamental. To make things worse, Barbara is mostly unfazed by the situation, and I suddenly understand that we are not the same, me and this woman. That even though she is nearing 80, the level of risk she is willing to live with is higher than that of almost anyone I know.

Then Barbara says, in a voice that’s flat and slow: “Go into the office and close the door.”

She distracts the cat just long enough for me to follow her orders.

When we eventually decide to exit the house, the relief of the outdoors only feet away, Barbara is quick to shut the sturdy metal gate behind us. (Peggy Sue is already trying to nudge it open.) I look back through the screen and, for the first time since my arrival, I see the lynx head-on. The size of her eyes is striking and alien. She looks magnificent, like an animal out of ancient times, from an ancient place. A creature of instinct.

When Barbara returns from dinner, this is the face that will greet her. She will not think of the power of the animal’s jaws, or the size of its teeth; she will step right inside. It’s been a very long time since Barbara Williamson was not the master of her own house.

Update, 6/8: An earlier version of this story incorrectly noted Jonathan Dana’s alma mater. It is Dartmouth, not Harvard.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook