So You’ve Been Banned From America. What’s Next?

Where are you headed? (Photo: Nick Harris/Flickr)

Imagine that you’re an American, leading, for all intents and purposes, a relatively successful American life. You have a decent job, good friends, more than enough money to get by. But then, for one reason or another, you have to leave the country, forever.

Maybe you committed a crime of passion, and you’re determined not to go to jail. Maybe you engaged in a principled act of protest, à la Snowden, that’s now threatening your freedom. Maybe the political climate has drastically changed and all of sudden it’s clear that if you stay here, you’ll be confined because of your ethnicity, your religion, or your political beliefs. Whatever the reason, you need to get out of town, and you can’t come back.

So where do you go?

Answering this question is an exercise in escapist fantasy and mundane realism. There’s no one right answer, because there are a number of factors to weigh. How long will your money last? Will you be able to get a job? Do you want to live somewhere English-speaking? Does climate matter? How about food and scenery? Will you go stir crazy if the country is too small and you can’t cross borders? Ultimately, this is the challenge: Imagine starting an entirely new life somewhere. Then imagine you could never come back home.

The first obvious answer is that you’d want to go some place pleasant and easy to live, like Costa Rica, the Netherlands or a Scandinavian country—pick your favorite. And, depending on your reason for leaving, that may be possible. Roman Polanski, after all, spent three decades in France. (This would require some advance planning, though: Polanski had lived in France for a number of years before he fled his sentencing in the U.S., and had become a naturalized citizen there.)

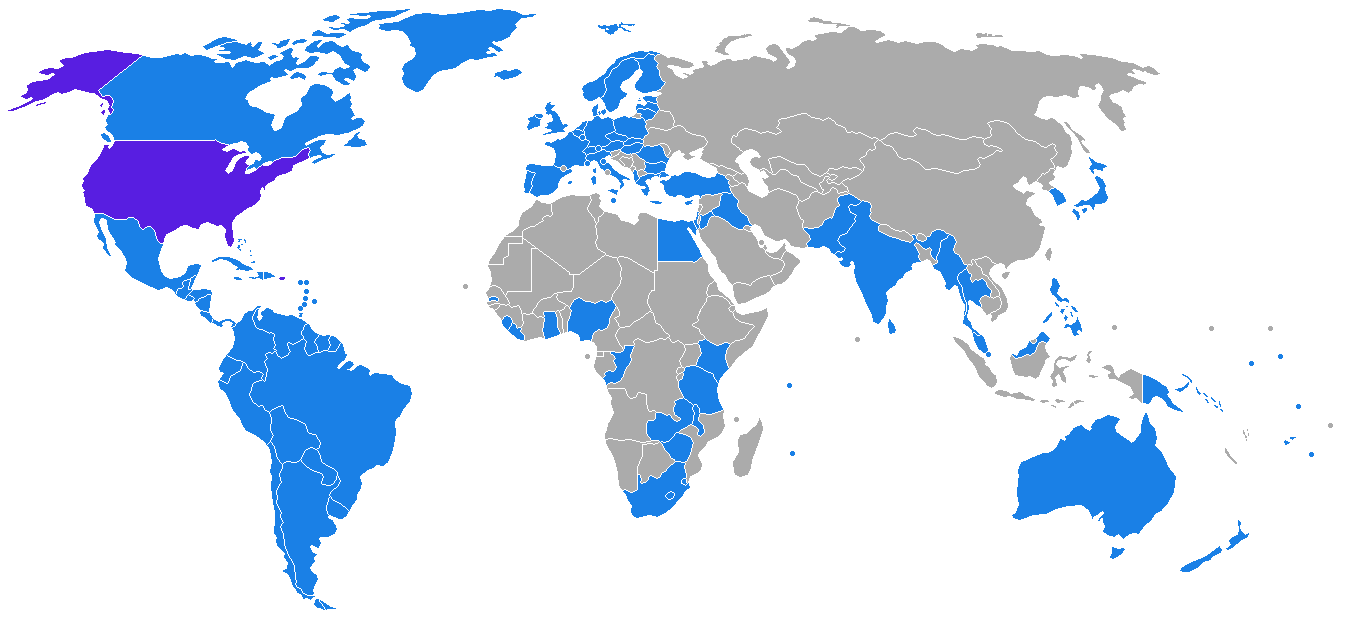

But if you were worried about the U.S. government tracking you down, for whatever reason, or your newly adopted country sending you back, you’d need to pick a country without an extradition treaty with the U.S. Then, your options become more limited.

Any place in blue is off-limits, since it has an extradition treaty with the U.S. (Image: CRGreathouse/Wikimedia)

It’s easiest to think about this in terms of regions, to start out with. South America is out (although Venezuela could work for political refugees). Almost all of Europe would be off-limits: a few small countries in the Balkans would be options, as well as Belarus and Ukraine.

Most African countries, on the other hand, do not have extradition treaties with the U.S. You could move to Morocco, from which it’s relatively easy to access the rest of the continent. A number of West African countries, from Burkina Faso to the Ivory Coast and Senegal, would theoretically be safe, although the ones without extradition treaties are all French-speaking. Central and East Africa also have a number of candidates, but it might be wise to steer clear of too much political turmoil. (Although, again, depending on your reason for escape—what type of crime you’ve committed—maybe violence and political instability are up your alley.)

A better choice might be the southern part of the continent: In Namibia, for instance, English is the official language, and there are beaches, beautiful natural parks, giant red sand dunes and German-style beer. Also, any money you’ve managed to bring with you will likely last a lot longer than in pricey Europe.

In Namibia, you could also hang out with ostriches (Photo: Greg Willis/Flickr)

If you’re not worried about money—maybe your life savings are more substantial than most Americans’, maybe you pulled off an amazing heist—a handful of countries in the Middle East could work. Syria, right now, is probably not a good place to start a new life. But places like Qatar and Oman have very high standards of living…and very attractive tax policies.

You could also definitely go to Russia, a number of sprawling Central Asian countries or China. The weather isn’t great, and language would be a problem. But if it’s important that you have a big swath of the world to move around in, these might be good options.

Then there’s Southeast Asia. It’s more or less on the other side of the world from the U.S., which may, in this case, count as an advantage. Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam) seems like a pretty decent choice for a fleeing locale: there’s good food, a fair number of English speakers, and plenty of room to explore. Plus, it’s cheap enough to live there that you wouldn’t immediately have to worry about running out of cash.

In selecting a country, you might also need to consider how you’ll get there to begin with. It might be helpful to pick a country where a large enough bribe will work to get you across the border to begin with. And, come to think of it, depending on your situation, living in a country with some corruption might be an advantage in the long-term, too, since your position will always be somewhat shaky, legally.

There are ways to make this thought experiment even trickier: maybe you’re leaving the country for religious reasons, but there’s been a sharp turn in U.S. foreign policy, and you need to live somewhere without a history of discrimination against those of your religion. Or maybe you’ve just escaped from prison, and your funds are really limited. Though in the United States (and many other non-volatile countries), citizens generally don’t need to think about what the best choice for starting a life elsewhere would be, unless it’s by choice. Which is ultimately a huge privilege—and probably one worth hanging onto.

Russia seems to be working ok for Snowden (Photo: Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook