The Hidden Rules of the Puritan Fashion Police

Slashed sleeves, frizzed hair, or a gold hatband could land you in court.

In 1676, Hannah Lyman was in trouble. She was among three dozen or so young women who had been summoned to court: They had flouted the laws of the colony of Connecticut by wearing silken hoods. Among these “overdressed” women, Lyman was, apparently, the most rebellious and strong-willed. She appeared in court wearing the very silk hood that she had been indicted for donning.

The judge was, predictably, not very happy. He accused her of “wearing silk in a flaunting manner, in an offensive way, not only before but when she stood presented” at court. She and the other young women were fined for their offensive sartorial choices.

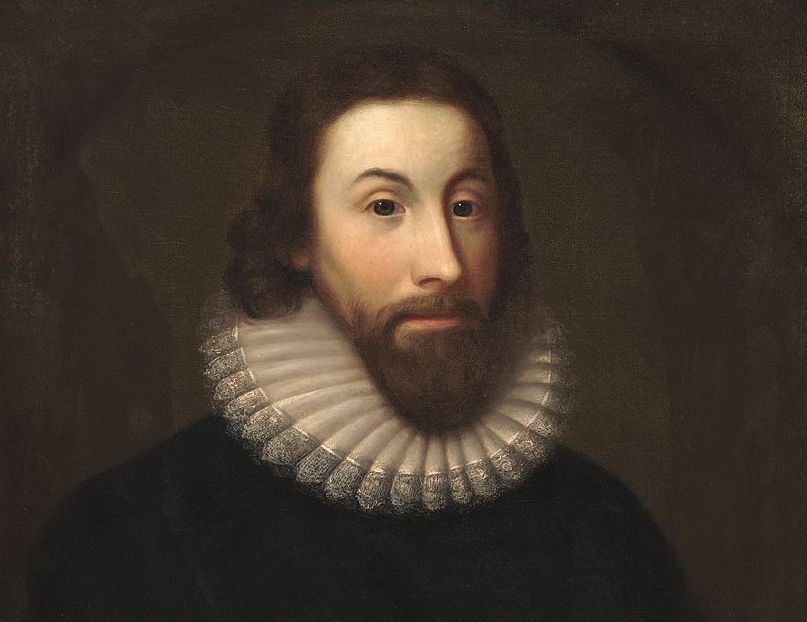

New England’s Puritan colonies had many laws restricting how citizens—particularly women—could dress. “Sumptuary laws” like these weren’t unique to that time or place; they had governed personal behavior as far back as ancient Rome. Usually sumptuary laws were enacted to control behavior in order to distinguish the high classes from the lower ones, though sometimes they were intended to keep wealthy-enough people from squandering all these resources on fashionable indulgences. Pirates’ dramatic and colorful style of dressing was, for instance, a deliberate and brazen violation of these laws.

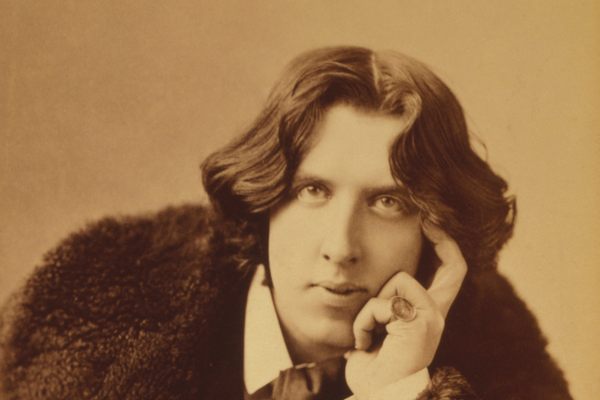

But Puritans, being Puritan, gave sumptuary laws a particularly moral cast. Dressing in a simple manner meant avoiding the sins of pride, greed, and envy, especially for women. In The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne make this point explicitly when he described the scarlet “A” that Hester Prynne wore on the breast of her gown, made “in fine red cloth, surrounded with an elaborate embroidery and fantastic flourishes of gold thread.” This letter, Hawthorne writes, “was of a splendor in accordance with the taste of the age, but greatly beyond what was allowed by the sumptuary regulations of the colony.”

The Massachusetts Bay Colony passed its first law limiting the excesses of dress in 1634, when it prohibited citizens from wearing “new fashions, or long hair, or anything of the like nature.” That meant no silver or gold hatbands, girdles, or belts, and no cloth woven with gold thread or lace. It was also forbidden to create clothes with more than two slashes in the sleeves (a style meant to reveal one’s rich and fancy undergarments). Anyone who wore such items would have to forfeit them if caught.

For decades the colony continued to refine these laws. In 1639, the colony instituted a stricter law against lace and forbade clothes with short sleeves. In the 1650s, the law became more class-conscious. Only those who had more than 200 pounds to their estates were allowed to wear gold and silver buttons and knee points, or great boots, silk hoods, or silk scarves. Exempt from the rule were magistrates and public officers, their wives and children, as well as militia officers or soldiers, and anyone else whose with advanced education or employment, or “whose estate have been considerable, though now decayed.” In 1679, the colony also started worrying about hair, since “there is manifest pride openly appearing among us by some women wearing borders of hair, and their cutting, curling, and immodest laying out of their hair.”

Massachusetts and Connecticut were not the only colonies to pass such laws. In New Jersey, by 1670, it was illegal for a woman to “betray into matrimony any of His Majesty’s male subjects, by scents, paints, cosmetics, washes, artificial teeth, false hair, Spanish wool, iron stays, hoops, high-heeled shoes, or bolstered hips.” And if they did? The marriage would be “null and void.” Oh, and they would be punished exactly as if they had been convicted of witchcraft or sorcery.

Eventually, even Puritan New England relaxed, kind of, about the way its people were allowed to dress. Although the laws remained on the books, they weren’t always enforced with vigor. This is in part because the punishments didn’t provide much deterrent. Six years after Hannah Lyman flouted the court with her silk hood, another magistrate went after a different group of women for the same offense. But that second time, no one else in the community was interested in indicting them. Law or no law, Puritan women were going to indulge in sinful extravagance, at least every once in awhile.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook