The Quest to Preserve Syria’s Cassette Tape Era

Keeping sounds, stories, and cultural memory alive through years of conflict.

Mark Gergis has had what he calls an “obsessive” love of music since he was a child. Born to an Iraqi father and American mother, Gergis grew up in Oakland, California, listening to Iraqi music at home or at family weddings in Detroit, Michigan, where a lot of his family is based. Eventually he took a broader interest in Arabic music as a whole, but there wasn’t much of the genre in the American market in the 1990s. So Gergis had just one option to feed his growing obsession. He had to travel.

Gergis had come of age during the time of the Gulf War (1990–1991), so he was aware of how negatively Iraq—and indeed the entire Arabic-speaking world—was perceived in the United States. “You really had to read between the lines and even ignore friend calls to not go because they thought it would be dangerous,” he says. Gergis had been researching Syrian music, so that’s where he settled for his first trip, in 1997. It was a step that opened up an entire world to him, one that began from personal research and curiosity, but would result in the creation of a public archive to preserve a special part of Syrian cultural history.

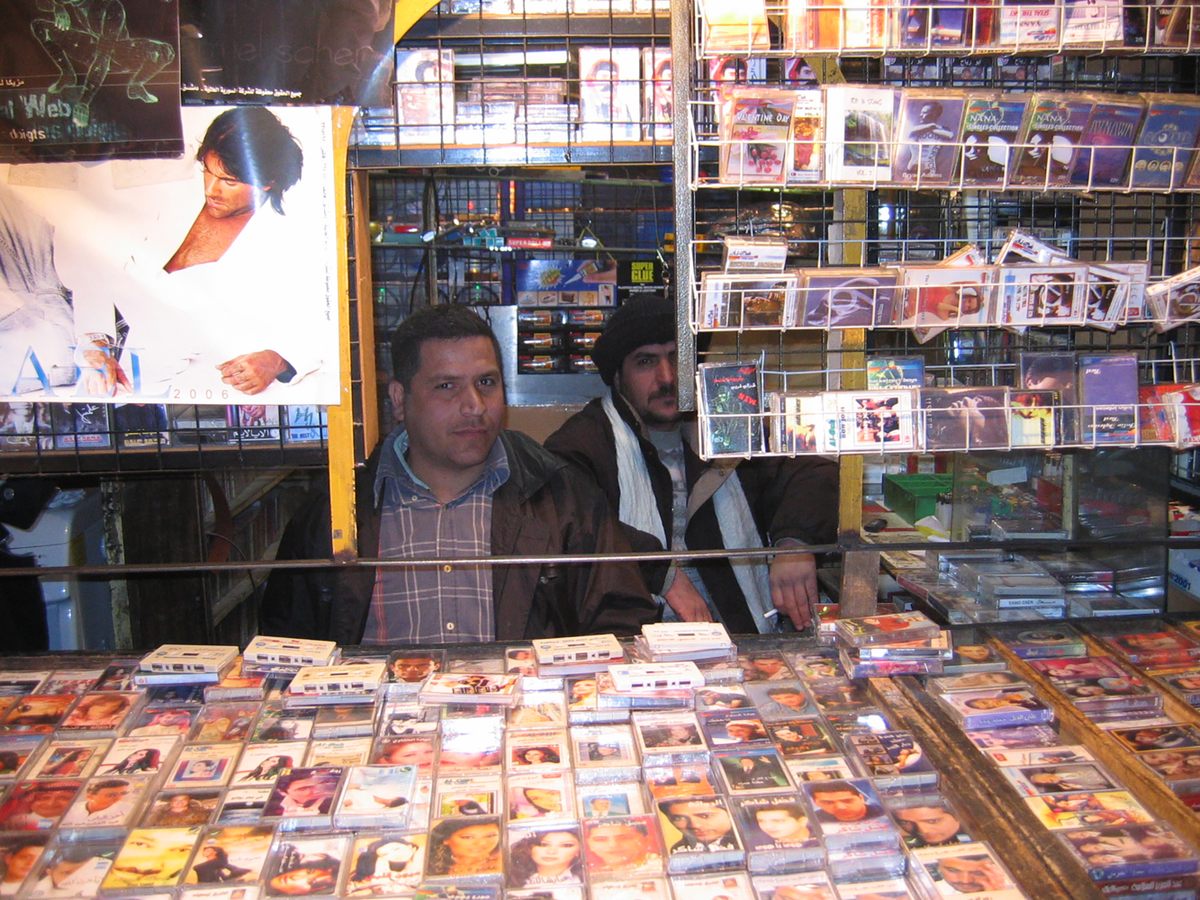

“In my travels, I bring a radio and a cassette deck,” Gergis says. While in Syria, he bought as many cassette tapes as he could, and eventually fell in love with the country. “There was music everywhere,” he explains. “On the streets, in cassette kiosks, and shops.” He continued to travel to Syria and by the end of the decade he had amassed a large collection of cassettes. Gergis was building a diverse collection of recordings of live concerts, studio albums, classical and children’s music, and even cassettes from artists from around the region, such as Iraqi folk singer Mona Al Abdullah. But he also had a specific focus on regional shaabi and dabke folk music, performed by Syrian artists such as Sulaiman Al-Shaar and Nermin Ibrahim.

Gergis’ last trip to Syria was in 2010, just before the outbreak of the civil war. He watched from the United States as the lives of the contacts and friends he made in Syria were completely upended. “It was really heartbreaking for me as an outsider who loved the country and loved the music to watch the dislocation and the trauma,” he says. Gergis wanted to do something to give back to the country that had given him so much.

By 2010, Gergis had amassed between 500 to 600 cassettes of music from Syria and around the region. As the primary recording format for at least four decades, the cassettes in the collection represented a huge part of contemporary and classical Syrian musical history. In 2017, while based in London, Gergis began digitizing his collection and by the next year his passion turned into what is today the Syrian Cassette Archives, an initiative to preserve and share the sounds and stories of Syria’s vibrant cassette era, from the 1970s to the 2000s. Along with his cofounder, Yamen Mekdad, a Syrian producer, music researcher, and DJ also based in London, the website currently displays 103 fully digitized cassettes, with many more to come from Gergis’s own collection and from contributors and collaborators. The archive includes interviews with musicians and producers from the era, many of whom have never spoken about their work on any platform. It is more than just about the music, but also the stories and culture it created.

According to the archive’s website, the cassette medium transformed the country’s musical landscape when it was introduced in the 1970s by providing an accessible platform for many musicians to record and distribute their works in ways they couldn’t before. Mekdad says that the cassette democratized music production and distribution, not just in the Middle East, but across the Global South. “Prior to the cassette, people had to make it to a certain level in their careers as serious artists in order to go to recording studios,” he says. Musicians who mainly performed at weddings or village festivals were suddenly able to just press record during their performances. The recordings helped boost their visibility and expand their reach into neighboring areas and even other countries: Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, Libya, and more. With time, Mekdad says, “People gained the skill sets and experiences, and a lot of the cassette shops that opened in those villages started to become places where musicians would record and sell their tapes.” Syria eventually became a hub for the entire regional market.

When the civil war began in 2011, these musical networks began to be disrupted by destruction and displacement. According to the UN Refugee Agency, nearly seven million Syrians have been forced to flee their home country since the start of the war, with just as many internally displaced. Many creators and producers in Syria fled. Mekdad, who was born and raised in Damascus, left for London at the end of that same year. According to him, production of cassette tapes in Syria isn’t happening much anymore, though the tradition continues through people’s personal archives and collections—and memories.

As Ammar Azzouz, an architect and lecturer in heritage studies at Essex University and research associate at Oxford University, puts it, the landscape and cultural heritage of a place tends to be forgotten in times of war and conflict. Azzouz’s research focuses on the tangible and intangible destruction and reconstruction of ideas of home during and after such traumatic events. He says that initiatives such as the Syrian Cassette Archives allows for a different narrative of Syria to be told, one that isn’t rooted in just destruction. “It’s a story of dance, music, hope, and love,” he says. “When you listen to these songs, they tell you different stories and have a way of taking you back in time.”

In an essay in Items in the spring, Azzouz writes that “little has been done by news media, academics, and journalists to describe Syria as a welcoming and hospitable land where different communities once found refuge.” The Syrian Cassette Archives reflects the diverse cultures that once formed the culture, from Lebanon’s Tony Hannah to Iraq;s Ghezlan to Egypt’s Saleh Abdel Hai. The tapes have become an alternative way of remembering what Syria was and could be again.

Reconstructing memory and deciding what should be preserved—and how—is critical in times of conflict. “It’s an urgent matter to unearth these kinds of personal and professional histories and stories that haven’t been discussed,” says Gergis. “We hope that we can help preserve the memory and stem the cultural amnesia that can happen in the diaspora and even within the country as displacement continues.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook