Oh, The Places You’ll Go, When You Love to Climb Volcanoes

A photographer who can’t get enough of them set out to summit the tallest one on each continent.

The best day in elementary school was the one when we made volcanoes. We mounded clay into the shape of a conical mountain and carved out a little hole on top. In it, we nestled a little cup, where we mingled baking soda and dish soap plus a couple drops of red and yellow food coloring. Then we added some vinegar, and stood back with grins on our faces. The little mountain hissed, and the bubbly liquid streamed down the sides.

It was fun, but it doesn’t hold a candle to the real thing. Volcanoes can snuff out entire towns with rivers of lava, or blanket landscapes with ash. But that experiment shows why bigger active volcanoes are mesmerizing—awful and awesome in equal measure. When they loom over towns, volcanoes are existential threats, often quite beautiful before they become lethal; reminders that a placid surface can conceal churning and gurgling with the potential to literally change the face of the Earth.

Adrian Rohnfelder knows this fascination well. A photographer based in Germany, he has a virulent, incurable strain of a disease he calls the “firework virus.” Symptoms include a mix of wanderlust and keen curiosity that compels him to visit the tallest, farthest, most spectacular dormant or active volcanic peaks around the world—sometimes in the hope that he will be there when they spew.

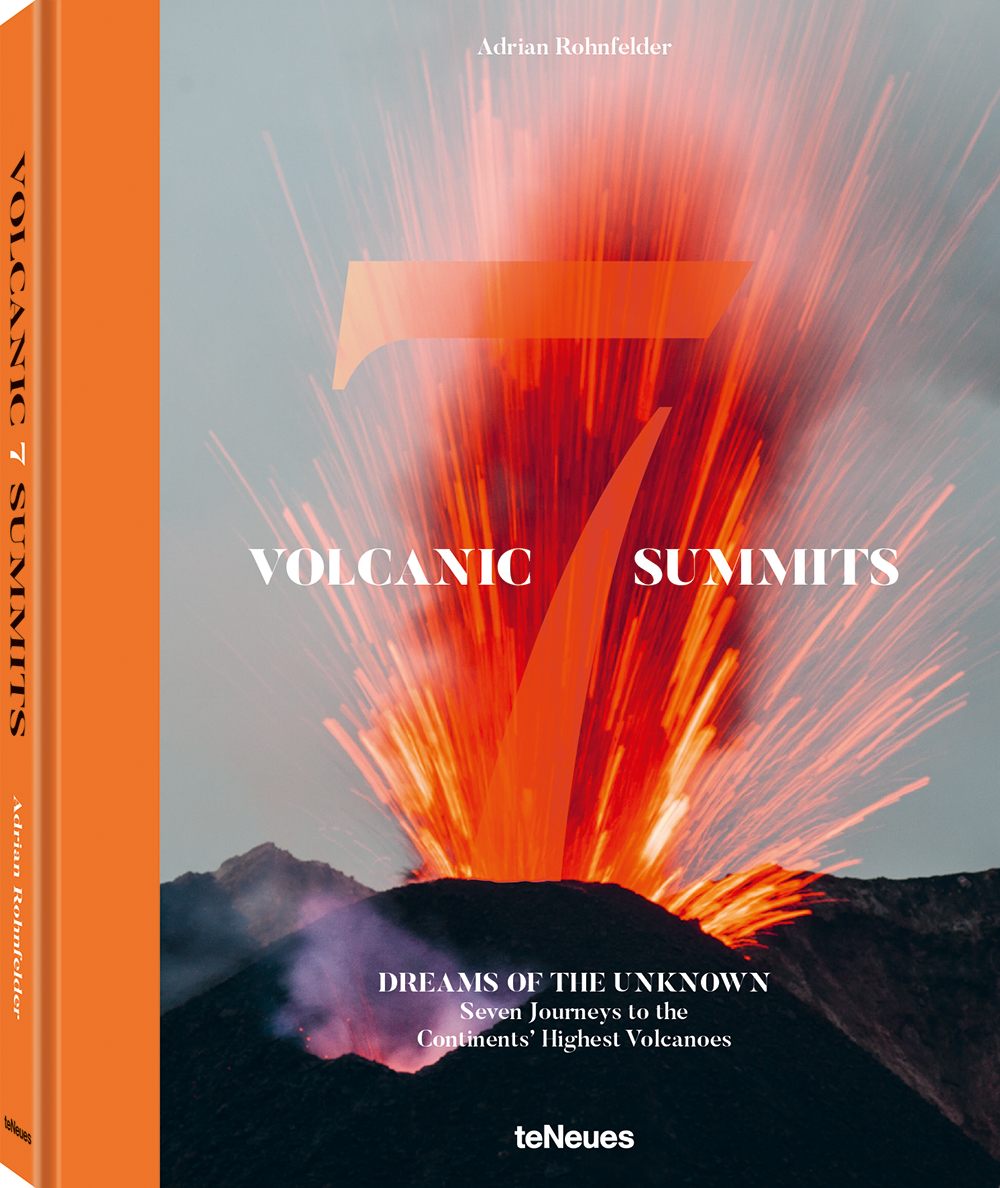

Rohnfelder has spent several years photographing these giants and chronicling the bumpy, chilly journeys to the top. His images are compiled in the new book Volcanic 7 Summits, published by teNeues.

Volcanoes do a lot more than blast plumes of gas into the sky or gush fountains of lava onto the landscape. Part monograph, part travelogue, Rohnfelder’s book takes readers to the icy swaths of Mount Sidley in Antarctica, and among the baobabs, deserts, and rainforests surrounding Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. From the salt lakes speckling the landscape around Ojos del Salado, in the Andes, to the snowy slopes of Mount Elbrus, in Russia’s Caucasus Mountains, to Mount Damavand in Iran, this book has a fair chance of infecting you with the “firework virus,” too.

Before you can photograph volcanoes, you have to climb them. All of Rohnfelder’s ascents were arduous, but some were particularly tough. “I really can’t stand cold and snow at all,” Rohnfelder says. “I prefer to be on the road where it is hot and dusty, and that will always remain my comfort zone.” While he used various modes of transit—cycling up Mount Kilimanjaro on an e-bike, for instance—he found that slow, steady steps were often best. Walking, he says, gives “the most time and peace for experiencing and photography.”

It’s not possible to visit every volcano on Earth—many are deep in the ocean—and depending on your appetite for frozen fingers and scorched lungs, you probably don’t want to visit all the ones on land, either. But Rohnfelder’s book taps into that elementary school fascination, and transports readers to stunning vantage points around the world where we can all appreciate the power below.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook