A Dead, Decomposing Whale Once Toured the United Kingdom

The Tay Whale brought together science, spectacle, and hucksterism in the quest to turn a buck.

In the winter of 1883, the Scottish city of Dundee was a good place for an enterprising showman, a frustrating place for a comparative anatomist, and a truly terrible place for a wayward humpback whale. That season, and for months after, a deep-pocketed oil merchant hauled a massive cetacean carcass across the United Kingdom and charged bystanders for an up-close glimpse, while a curious scientist named John Struthers did his best to tune out the crowds, the cameras, and the tooting band, and learn something.

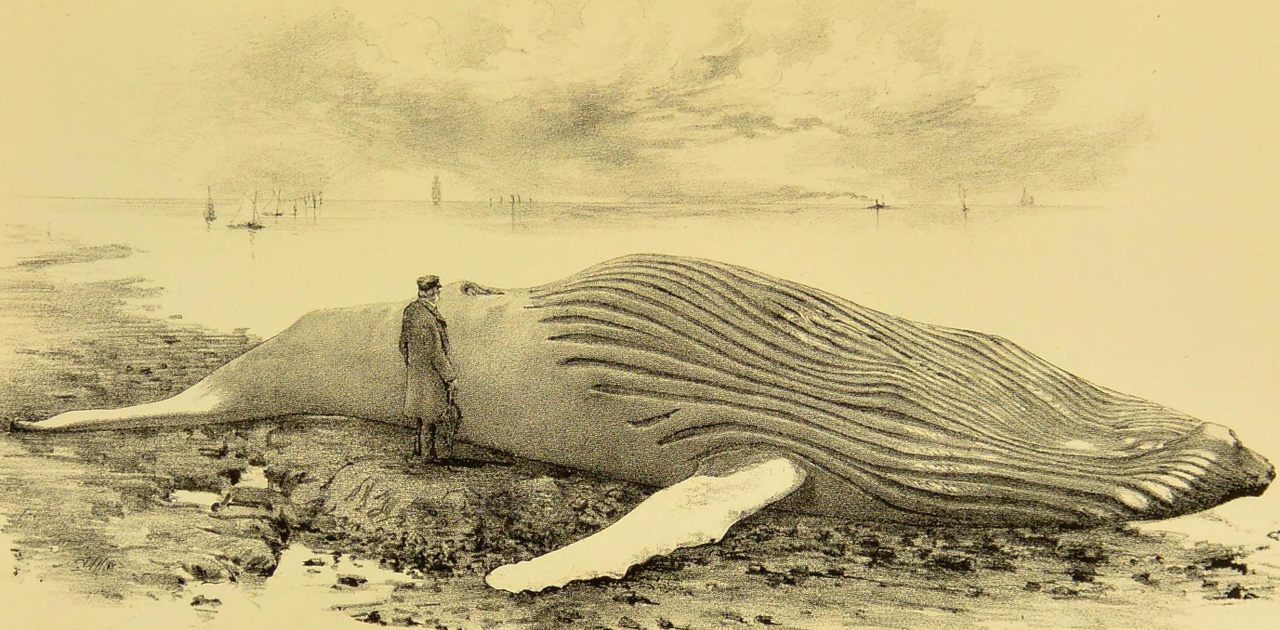

In December of that year, some local folks caught sight of a spout or fin in waters where they didn’t expect to, in the Firth of Tay, the estuary where Dundee sits. It was unusual to see a humpback so near the coast, and locals suspected it may have been enticed by a particularly large shoal of European sprat, a fish in the same family as herring. (Though humpbacks have a mouth full of baleen, most often associated with a diet of krill, they also feast on small fish.) The young whale had little chance of getting out alive. Whalers who cruised Arctic waters frequently wintered in Dundee, and at the time the city “was the premier whaling town of the British Empire,” said Mike Sedakat, curator of botany and zoology at The McManus in Dundee, where the whale’s bones would eventually come to rest and are still on display today, in a video produced by the museum. “So, unfortunately, this was very bad timing on this whale’s part.”

The sighting sent excitement rippling through town. “Many of the townsfolk knew about whales but had never seen one, and many came to watch it leaping out of the water, including adults who skived off of work and children who skived school,” writes Sedakat in an email. “After a few days, the whalers, both professional and amateur, decided to catch the whale.”

“On 31 December, the quarry was finally struck by several harpoons,” according to M.J. Williams, a consultant physician at the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, in a blow-by-blow account published in the Scottish Medical Journal more than a century later. Though the whale was hit by “a four-foot-long iron, two marley spikes and several nuts and bolts,” it ultimately snapped the harpoon line and swam free. But the whalers were “convinced mortal injury had been done.” A week later, they were proved right.

A group of fishermen approached what they believed to be a capsized ship, only to discover that it was the carcass of the whale that got away, Williams writes, still “bristling with the Dundonians’ hardware.” They towed it to shore in the town of Stonehaven, in Aberdeenshire. “The local pubs made a lot of profit from visitors who wished to see the whale and have a pint afterward,” Sedakat says. Soon, John Struthers sped over to take a look. A surgeon, comparative anatomist, and Darwin devotee, Struthers had set out to open a zoology museum at the University of Aberdeen, stocked with specimens that would illustrate Darwin’s theories.

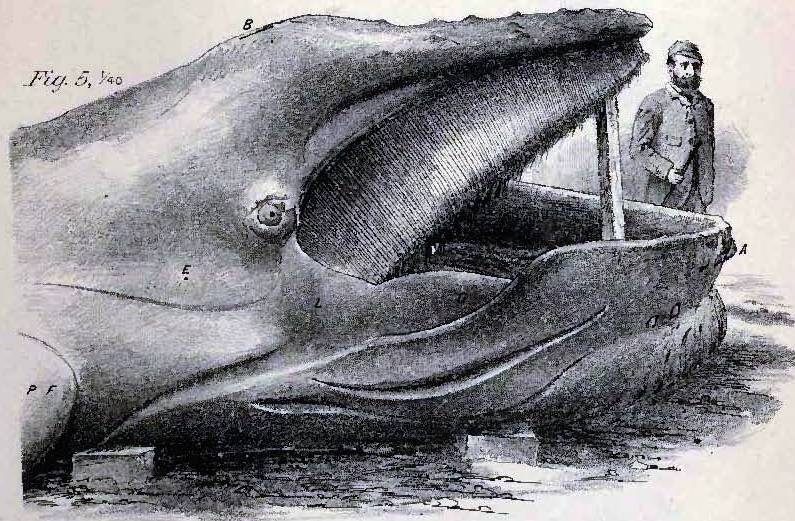

Struthers measured the whale, but he wasn’t permitted to cart it back to his lab. The fate of the 45-foot, 29-ton cetacean was decided at auction, where a local oil merchant named John Woods—“Greasy Johnny”—paid £226 (about $34,000 today). It came to be known as the Tay Whale, for the body of water it into which it had strayed. Twenty horses hauled the carcass half a mile to Woods’s scrap yard, Williams writes. It took 26 hours.

Almost immediately, Woods went into the souvenir business. He commissioned commemorative photographs of the whale, Williams writes, “whereby the dull surroundings of the yard were replaced by a scenic view of the Silvery Tay, with rail bridge and a sunset on imaginary hills.” And he began charging for views. On a single Sunday afternoon, 12,000 visitors paid to gawk. In a town of 200,000, some 50,000 turned out to see the whale. “Enthusiastic visitors even jumped on the whale’s back and did somersaults on it!” Sedakat says.

The exhibit inspired a poem by William McGonagall—a writer the Scottish Poetry Library has ruthlessly (and hilariously) derided for “his unwitting butchery of the art form,” laden with “erratic scansion, wince-inducing rhymes, and naif treatment of weighty subject matter.” McGonagall’s giddy “The Famous Tay Whale” ends:

Then hurrah! for the mighty monster whale,

Which has got 17 feet 4 inches from tip to tip of a tail!

Which can be seen for a sixpence or a shilling,

That is to say, if the people all are willing.

Though he had been outbid for possession of the whale, Struthers, the anatomist, still wanted a crack at it. Woods wasn’t keen to lose his cash cow, but he was willing to play along. The two cut a deal: Struthers could dissect the whale as long as Woods could invite the paying public to watch. The procedure would boast the “added attraction of background music by the band of the 1st Forfarshire Rifle Volunteers,” Williams writes.

Woods also needed Struthers to help salvage what was left of the decaying creature. Dead things smell terrible, and even in the Scottish winter the whale was decomposing fast. The creature “has not been looking quite his best since he was brought to terra firma,” the Aberdeen Journal reported on January 26, 1884, and with each passing day, the whale “became less attractive to the eyes, and especially to the noses, of its visitors.” Because so much of the carcass had rotted away, the paper added, it was getting harder to even tell what it was: Many were disappointed to discover after paying their entry fee that the whale’s “only recognizable feature was his tail.”

On a stormy day at the end of January, Struthers set to work—surrounded by a crowd and accompanied by a band playing tunes that were anything but solemn. He was dressed to the nines, in a top hat and tailcoat, according to Stuart Waterston, a plastic surgeon who coauthored an article about Struthers’s anatomical exploits. Struthers opened the animal “with a massive incision from umbilicus to anus,” Williams wrote, working through skin, blubber, and viscera before removing its heart. (He would go on to use the organ in lectures, the Aberdeen Weekly reported, to show the creature’s anatomy and speculate about how well-oxygenated blood helped the whale stay underwater for long stretches of time.) As Struthers worked, the decomposed “viscera and muscles … poured out in a messy pulp” up to his knees, Williams writes. The sprinkling of sawdust, meant to absorb the gore and the stink, wasn’t up to the task. “To anyone with a dainty nose,” the Aberdeen Journal reported, “it would be almost, if not quite, intolerable.”

After the dissection, Woods hatched a plan to extend the afterlife of his money-making scheme. He had the carcass embalmed, stretched over a wooden “backbone,” and stuffed back into some semblance of its original shape. He took the show on the road, carting it to Glasgow, Manchester, Newcastle, Edinburgh, and farther, the Glasgow Herald reported in 1884. The tour finally wound down in steamy August—seven months after the whale was killed—and Struthers dissected what was left of the body, including the head.

In one of the dissections, Sedakat says, Struthers stumbled across something surprising and sad: an unconscious human man inside the whale’s remains. “One of the audience recognized him as a homeless man from Fife, a district across from Dundee, who used to sneak on the ferry,” Sedakat says. “It is thought that he was looking for a warm place to spend the night and went inside the whale’s mouth whilst it was on a train carriage [traveling between cities]. Unfortunately he could not be revived, even with shocks from galvanic batteries and gunfire.”

There was at least one more stop on the whale’s postmortem journey: “Several lorry loads of the flesh and bones were then packed up and consigned to Aberdeen University,” the Herald stated, where Struthers would prepare an articulated skeleton.

But whale skeletons can’t go on display right away: They’ve got to be stripped of any lingering flesh—a task that can involve compost and hungry beetles—and degreased to remove the oil that suffuses their bones. The entire process is a slog. By May 1887, nearly three years later, Struthers predicted that they still had a ways to go. “The smell is still strong in those of them which remained so long in the body during the time it travelled, the contact with the blubber having both discolored them and apparently made them more full of oil,” he was quoted as saying in the Aberdeen Journal. “I believe it will take the sunshine and wind of the whole summer before they are sweet enough to be placed in a museum without offense to the visitors.”

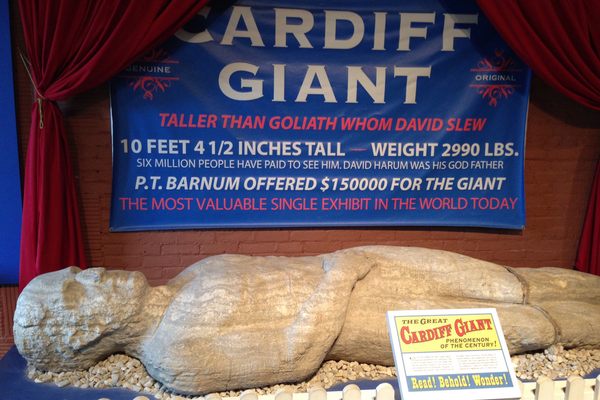

The whole performance—the auction, the attraction, the dissection, the tour—were in keeping with a kind of rogue showmanship that was in vogue at the time. Other hucksters had lured paying visitors with the promise of something natural-seeming, wondrous, and unfamiliar. There was the mediocre statue billed as the Cardiff Giant, excavated in New York in the 1860s and touted as a petrified man—evidence that biblical giants once roamed the Earth. P.T. Barnum, not one to let such a moment pass him by, commissioned his own copy of the hoax, and already had a history with the so-called FeeJee Mermaid, a sharp-toothed, taloned, scaly creature that is part carp, part papier-mâché, and zero percent mermaid. That little pastiche of a creature eventually wound up in the collection of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. “It speaks to early museums and early collecting practices, which are a mix of scientific natural history and the spectacle,” said Diana DiPaolo Loren, a curator at the museum, in a university video. “And this clearly is the spectacle.” Unlike those examples, the Tay Whale was real flesh, blood, and blubber—but it shared with those other examples the 19th- and 20th-century impulse to merge science, entertainment, and creative license to turn a buck.

“The inhabitants had mixed views” about the famously killed whale, Sedakat says. “Many condemned the carnage inflicted on such a magnificent animal.” The writer of the 1884 Aberdeen Journal article about the whale did chew over whether it could have been an attraction and still be left to its watery life. “He might have taken kindly to the beautiful estuary which forms the mouth of the river, and paid it periodic visits—and surely that would have been honour enough to Dundee,” the writer mused.

But presented with an opportunity to make a buck, the writer ultimately concluded, who could say no? When life gives you a whale—in this case, less “given” than “taken,” with great sweat and expense—you make the most of it. The same impulse nearly drove the humpback and other whales to extinction, and threatened many other species. “The purpose of converting [the whale] into as much money as possible was one of the most natural that could be entertained,” the reporter wrote. That sense that the money-making instinct is “natural” and something to be celebrated is what sent the creature on its long, stinking, sad journey across a country—even as it fell to pieces before viewers’ eyes.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook