The Amateur Radio Obsessives Who Send Messages from the Ends of the Earth

Bob Allphin’s DXpedition’s Main Operating tent on Peter I Island, Antarctica, with six 1 kilowatt stations. (Photo: Peter I DXpedition Archives)

In 1993, Bob Allphin and a team of 11 other men took a boat to remote Howland Island, an uninhabited slip of coral that is officially part of a group called United States Minor Outlying Islands located in the Pacific Ocean.

It’s not a place where tourists tend to gather, save a very specific breed. “If that rings a bell,” says Allphin, “It’s because that’s the island Amelia Earhart was looking for when she ran out of gas and disappeared.”

The trip was going according to plan, but as the week progressed, the waves offshore grew larger and larger.

Powerless, the small gathering could only watch as the whitecapped water separated them from their main vessel. With ample supplies visible off shore, they ran out of water.

“And there’s no worse feeling because you’re on an island where the temperature is 120 and you’re thirsty as hell,” says Allphin.

The dozen tourists combed the beach for upturned seashells filled with rainwater and strained that through a t-shirt into a bucket, adding iodine pills. This was the stew they planned to subsist on when they had a breakthrough—the crew was able to get water ashore. Still, they wound up stranded on the island an extra seven days.

Antennas set up on Niue, a tiny island in the South Pacific Ocean, and location of one of Don Beattie’s DXpeditions (Photo: Hilary Claytonsmith)

Perhaps the most shocking thing is that this group risked their lives for a passion that is esoteric even by esoteric tourism standards—they weren’t out at the remote island for Amelia Earhart. They were there to make contact with as many amateur radio operators from all over the world as possible.

According to the American Radio Relay League, which is the national membership association for amateur radio operators in the U.S., there are around 3 million operators worldwide. Amateur radio (which is also known as ham radio, and its users as hams) is, simply put, non-commercial use of radio frequencies to communicate. Amateur radio operators typically apply for a license from their country’s governing body—in the U.S. there are three levels of licenses with ascending privileges, which are earned by taking written tests. Operators assemble their own small stations, including transceivers and antenna. Once setup, some are content just to talk with fellow Hams, reveling in the thrill of chatting with a stranger several states or oceans away. There are some who like to bounce radio waves off the moon. There is “contesting”, where operators compete to contact the most people within a short amount of time. There’s DXing, an obsession with contacting those stations farthest away from the operator. And there’s DXpeditions, where intrepid hams travel to far flung places with little to no operators and set up stations so their global community can knock a new location off their list.

DXpeditioning has existed in some form since the early 20th century. Today, such trips take various shapes. There are small ones where operators fly in and out; some even stay in hotels or at spots maintained by fellow hams where equipment is at the ready. Then there are the big operations—treks to often uninhabited, remote outposts that take months of planning, teams of up to twenty people, and hundreds of thousands of dollars. Multiple flights are taken, boats chartered, shipping containers filled with tons of equipment, tents erected. Many of these trips are determined by Club Log, an online application that allows operators to upload confirmed radio contacts and pinpoint the least contacted places in the world, which make up the “Most Wanted”.

Operating one of the radio stations on Rodrigues in Mauritius. (Photo: Hilary Claytonsmith)

The top ten locations on that list are the Holy Grail of DXpedition sites. Journeying to those spots is what 71-year-old Georgia-based Allphin—who is retired from his job at a mutual fund—specializes in. Allphin has been on about 40 DXpeditions, 11 of them to Most Wanted locales. (DXpeditions reshuffle the top ten list, accounting for Allphin’s unintuitive count.)

There are a few reasons places land on the Most Wanted list.

“It’s either political, or it’s a government agency that’s trying to protect the wildlife, or it’s so doggone hard to get there you can’t afford it,” says Allphin.

North Korea, which hasn’t been worked in over a decade, is number one on the Most Wanted list. (Polish radio amateur Dom Grzyb recently announced that he was inching closer to gaining approval to operate in the country.)

DXpeditioning does involve some of the romantic trappings of exploration—desolate snowscapes, tropical beaches, rough sea journeys, and wild animals. It also involves a lot of red tape, physical labor, and planning—and all for the love of racking up amateur radio contacts. If this sounds like fun, you might be a DXpeditioner.

Here are some things to consider: Negotiating access to hotspots like Bhutan, which restricts tourism, or Navassa Island in the Caribbean, which is overseen by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, can take years. It took Allphin’s team over a decade to get permission to set foot on Navassa, which they visited in January. Because you often pack in all your supplies, including radio equipment, there are customs authorities to grapple with and taxes (or trying to avoid taxes). There are other expenses to consider, from helicopter rides to paying for the oversight of Fish and Wildlife employees.

Bob Allphin’s DXpedition group to Antarctica. (Photo: Peter I DXpedition Archives)

Allphin has embarked on trips with price tags surpassing half a million dollars. In order to defray costs, many expeditions set up donation pages and organizations such as the Northern California DXpedition Foundation and the Yasme Foundation mete out grants.

Now that you’ve planned and executed your often many legged journey, the sweating begins.

Upon arrival, you must erect your “radio city”, as Allphin calls it, where you will live for several weeks, sleeping and working in 24-hour shifts in order to make as many contacts as possible.

It can take two to three days to set up all the antennas and other equipment, according to Don Beattie, an amateur radio operator in the UK who has been on about 20 DXpeditions.

“And for many people, they come from halfway around the world so they’re jetlagged and in some cases they’ve had a particularly rough sea passage in the last couple of days,” says Beattie. “They arrive in less than tip top shape, so you have to be a little careful on how hard you drive the team to set up.”

And then of course, there are the vagaries of your destination.Salt air can be tough on equipment and Beattie has heard stories of operators showering with their antenna every 24 hours to scrub away salt. Allphin packed a cattle prod for his trip to Heard Island in the Antarctic, which he shared with elephant seals that can reach 16 feet and weigh over two tons. (He didn’t have to use it.)

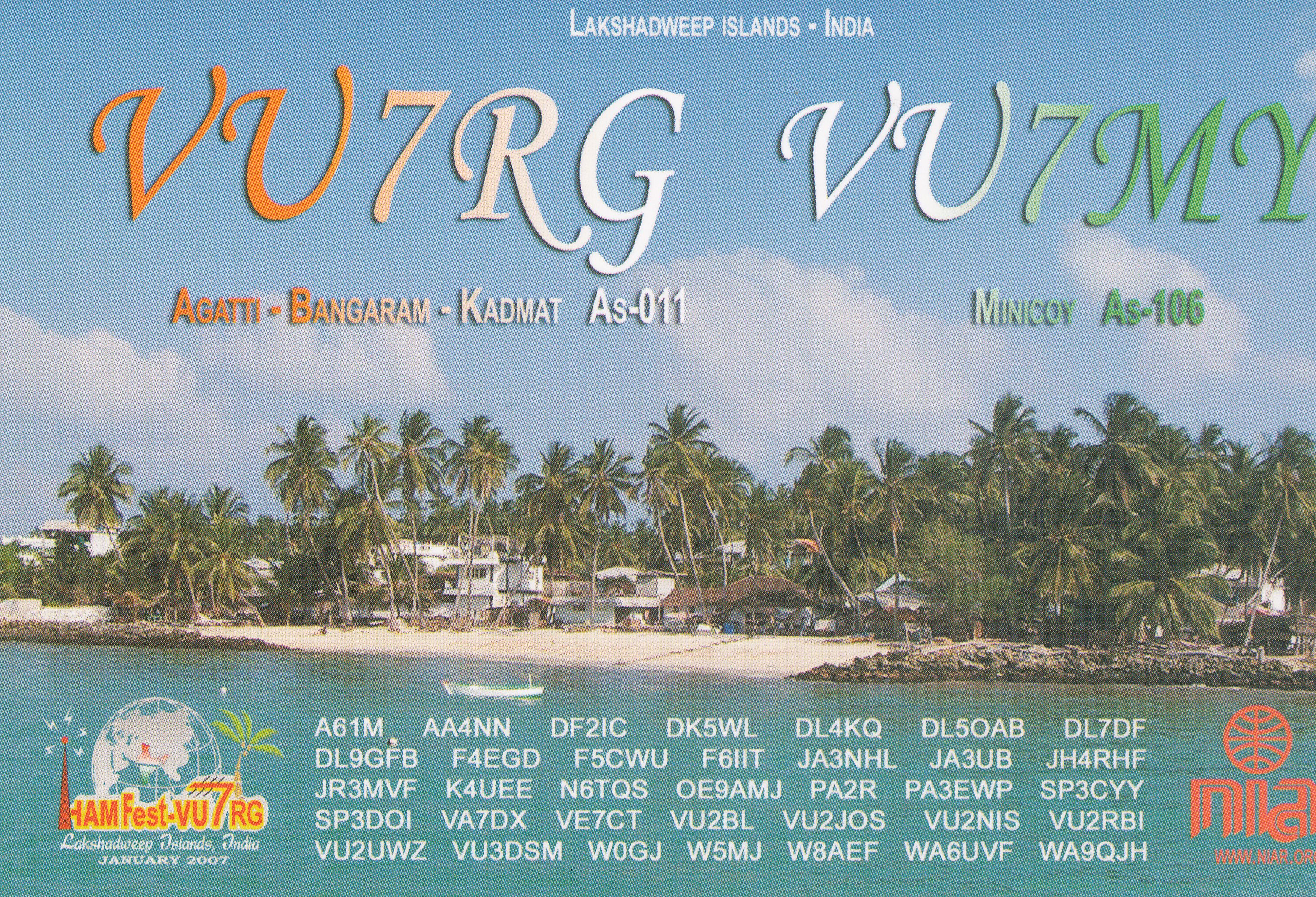

A QSL card from Bob Allphin’s DXpedition to Lakshadweep Islands in India. (Photo: Bob Allphin)

Once the radio city has risen, it’s time to start making contacts. DXpedtioners get the word out ahead of time via amateur radio organizations, expedition websites, and by taking out ads in niche magazines. The number of people trying to make contact with, say, Lakshadweep, an island in the Laccadive Sea off the coast of India, is not small. Such trips can result in well over 100,000 contacts. Allphin participated in a trip where 195,000 contacts were made. The result of thousands of people calling at the same time is a “pileup”—something DXpeditioners speak about with awe.

“When you tune across it, it just sounds like white noise,” says Beattie. “You can’t hear any speech, all you can hear is this incredible buzz as you tune across the frequencies. And knowing how to distill that down to the one call sign quickly and get a contact confirmed and then move on to the next one—that is one of the big skills.”

There’s no chitchat on a DXpedition—hams call the expedition and state their call sign, a series of letters and numbers that is essentially their radio name. (“Some of it is Morse [code], it’s not all talky talky,” says Beattie.) The team member that answers repeats this back to them, along with a “signal report”—usually the number “59”—meaning everything has come in loud and clear, and the transaction ends.

“That’s a big thrill, and frankly, I think it’s one of the motivations that a lot of DXers would say is primary,” says Allphin. “They are tested to the limit in those pileups.”

Once contact is made, it is commemorated with a “QSL card”, a postcard made specially for the trip and sent via post. (Coordinating the sending of the postcards represents yet another logistical project.)

Bob Allphin on St George Island. (Photo: Peter I DXpedition Archives)

DXpeditioning is not without its risks. In 1982, two German hams on a trip to Amboyna Cay in the South China Sea were killed when occupying forces attacked their ship.

DXpeditioner Charles “Rusty” Epps had his own brush with death in 1974 on a trek to the Palmyra Atoll in the Pacific Ocean.

“All that is, is a pile of busted coral and seashells that the tides and waves have stacked up on a reef,” recalls Epps.

While they were there another boat, carrying a man and woman, lodged itself on the reef. Epps and his team paddled out in dinghies and helped pull them ashore.

“We knew they were strange and would not have wanted to stay with them,” says Epps. “But we were leaving the next morning anyway.”

Not long after the DXpeditioners took off, a yacht arrived bearing an adventurous and wealthy couple from San Diego, Malcolm and Eleanor Graham. subsequently vanished. The couple that Epps helped rescue, Buck Duane Wlkaer and his girlfriend Stephanie Stearns. later surfaced on the stolen yacht. Eleanor’s bones were discovered in 1981; Malcolm’s was never found. Walker was convicted of killing Eleanor; Stearns, who was represented by Vincent Bugliosi, the attorney that prosecuted serial killer Charles Manson, was acquitted. The saga was turned into a TV movie and chronicled in a book by Bugliosi.

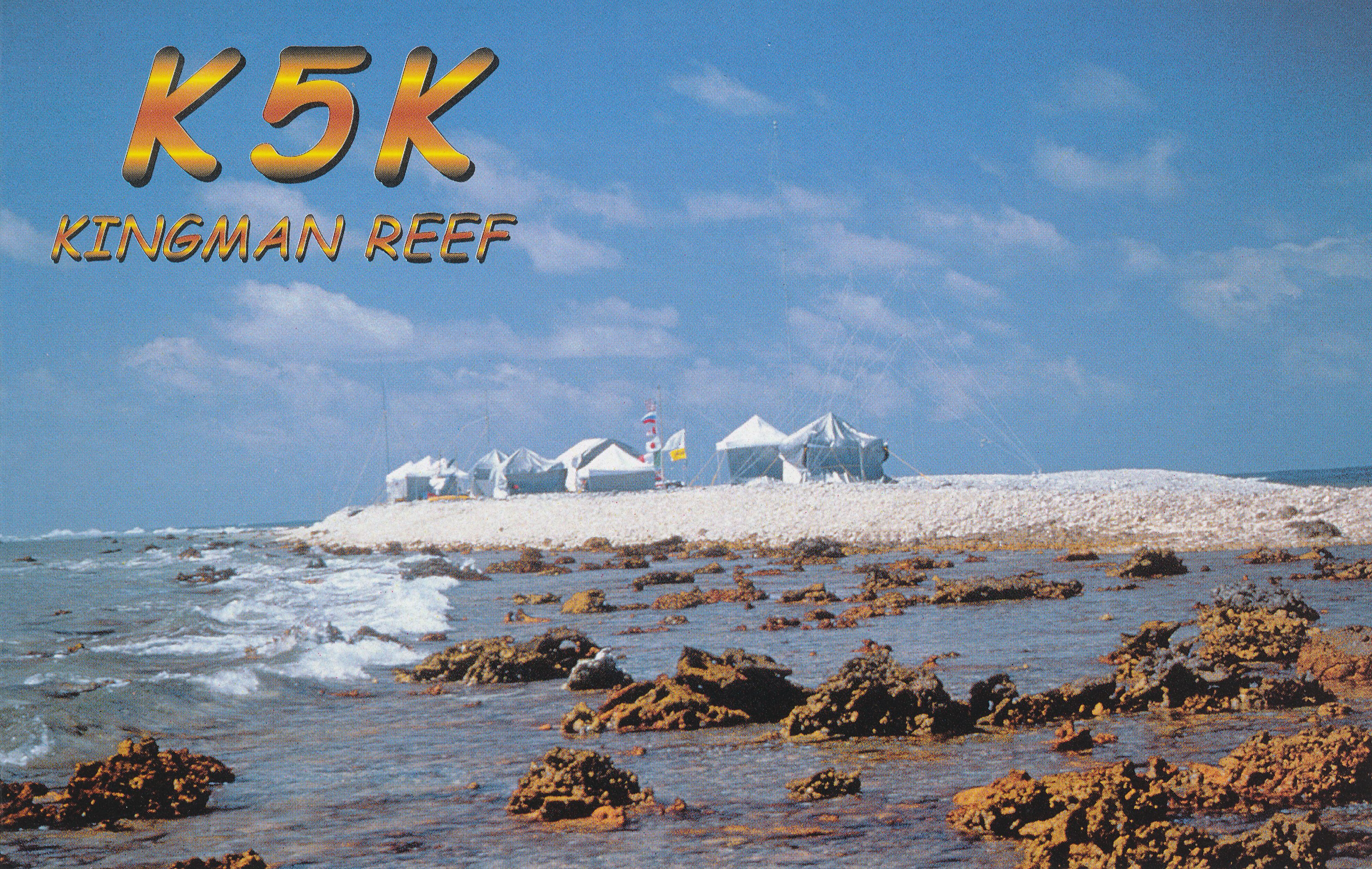

A QSL card from a trip to an uninhabited reef in the Pacific, Kingman Reef. (Photo: Bob Allphin)

“It became so clear that had we stayed, we could have been the ones murdered,” says Epps.

Most risks run by DXpeditioners are not so dramatic—in addition to the time he had to hunt and gather water on Howland Island, Allphin recalled his second sketchiest moment as that of being forced to leap from the shore of an Antarctic island into a Zodiac boat.

“It was an ugly, ugly place,” says Allphin. “There were about five million penguins there and the penguin poo was very deep. It was raining and we were stuck in that stuff.”

As he prepared to jump, his mind was on a nearby leopard seal, a predator that looks a little bit like Voldemort.

“The worst case scenario that was going through everybody’s mind was, ‘I miss the boat, I end up in the water and I have to contend with this leopard seal,’” says Allphin. (He made it.)

Leopard seals, arduous journeys, bureaucracy and occasional mayhem have hardly deterred hardcore hams from their quests.

“It’s a cocktail of things, I think, really,” says Beattie. “First of all, it’s the challenge of doing it. Why do you climb Everest? Because it’s there. Why do we do this? Because it’s fun doing all the planning, it’s a hell of a lot of fun getting there, and it’s a hell of lot of fun when you get there.”

Penguin poo nonwithstanding, Allphin, who earned his amateur radio license when he was 14, says he will next turn his attention to destinations in the Pacific. “Amateur radio is pretty much the greatest hobby in the entire world,” he says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook