The Bloody Histories and Remaining Relics of 5 Violent Feuds

Things get heated.

In honor of Rivals Week this week, here are five relics of the bloodiest family feuds in the Atlas.

Tewksbury vs. Graham - Flying V Cabin of John Tewksbury

PHOENIX, ARIZONA

The Flying V Cabin of John Tewksbury, Sr. (Photo: Marine 69-71 / Wikipedia)

The Flying V Cabin of John Tewksbury, Sr. (Photo: Marine 69-71 / Wikipedia)There was very little pleasant about the Pleasant Valley War. The Tewksbury-Graham family feud started like so many others before it. Two neighbors, friends at first, slowly fell into a dispute. It was family patriarch John Tewksbury Sr., who lived in the above cabin, who invited his friend Tom Graham out to Arizona to begin ranching. Soon however, even the vast expanse of the Southwest began to feel cramped. Both families started accusing the other of stealing horses and cattle. The accusations soon turned to arrest warrants.

In 1885 a Basque sheepherder working for the Tewksbury family was killed by a member of the Graham clan and suddenly the entire valley exploded. For the next three years it was all out war involving multiple other ranchers, hired hands, and the investors of both rancher families. A group of cowboys called the “Hashknife outfit” got involved. They were known as the ”thievinist, fightinest bunch of cowboys” in the U.S. People were beheaded, ranches were burned to the ground, an assassin was hired, and lynchings, murders, and shootouts became commonplace. The feud played like a super-cut of spaghetti Westerns climaxes.

The war lasted six years and had the largest death toll of any family feud in US history. By the end of the battle nearly every male in both families, save a single remaining Tewksbury son, was dead.

The Regulators vs. Moderators - Centennial Marker

SHELBYVILLE, TEXAS

In 1839 when Texas was still its own Republic, on its border with Louisiana, in a lawless patch of land, all hell broke loose. In Shelby County, a small memorial marker tells the tale.

Running along the western edge of Louisiana and eastern edge of Texas was a strip of land that no country claimed. Known as the No Man’s Land of Louisiana, for fifteen years from 1806 to 1821 it was outside the legal jurisdiction of any country due to a disagreement over the borders of the Louisiana Purchase. Criminals, political refugees, swindlers, deserters, and exiles of all stripes flocked to the no man’s land. In 1821 the border was settled but the land was still lawless.

The “Regulators” formed to regulate these illegal activities. The “Moderators” did not care to be regulated and sought to moderate the Regulators into an early grave. It was such a mess that president of the Republic of Texas Sam Houston thought that perhaps it would be best to just to stay out of it and let the area descend into all out warfare. As he put it ”I think it advisable to declare Shelby County, Tenaha, and Terrapin Neck free and independent governments, and let them fight it out.” Ultimately the two sides were forced to disband but by the end of the Regulator-Moderator War over 40 people had been killed.

Three years after the supposed settlement of the war, a moderator invited a number regulators to his daughter’s wedding as a peace offering. He had poisoned the wedding punch which sickened 60 and killed 10. The poisoner was lynched. So much for the truce.

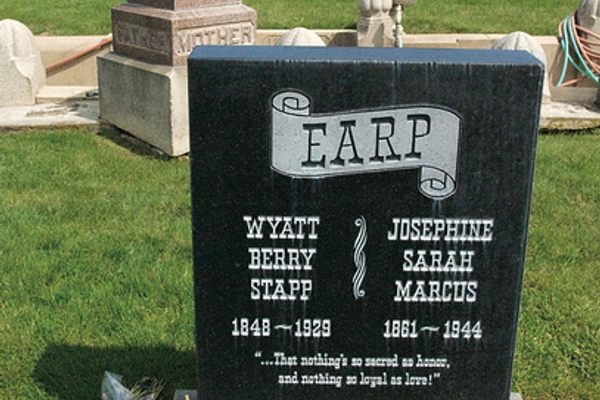

Wyatt Earp & Doc Holiday vs. Cowboys - Graves of Earp and Holiday

COLMA, CALIFORNIA & GLENWOOD SPRINGS, COLORADO

Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday took part in what is perhaps the most famous feud-driven gunfight of all time, the infamous Gunfight at O.K. Corral.

Despite it’s fame, the fight only lasted a total of 30 seconds and did not in fact take place in the O.K. Corral but instead on the side of a photographic studio about six doors down. However, within that 30 seconds nearly 30 shots were fired by gunmen as close as six feet away from each other. The feud that produced the famous gunfight was extremely complex, but can largely be boiled down to the Earp family and Doc Holiday vs. all cowboys. Following the gunfight, which left cowboys Tom McLaury, Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton dead, the feud simmered on, and the Earp brothers were attacked a few days later, with one maimed and the other killed.

Despite being such towering figures in Western mythology and both having been involved in numerous gunfights and disputes, they both died peacefully. Doc Holliday died of tuberculosis in a Glenwood Springs sanitarium and Earp died at the age of 81 with his wife Josie Marcus at his side. They also remained friends throughout their lives. Earp had this to say about Holliday:

“Doc was a dentist not a lawman or an assassin, whom necessity had made a gambler; a gentleman whom disease had made a frontier vagabond; a philosopher whom life had made a caustic wit; a long lean ash-blond fellow nearly dead with consumption, and at the same time the most skillful gambler and the nerviest, speediest, deadliest man with a six-gun that I ever knew.”

Capone vs. Moran - St. Valentine’s Day Massacre Wall

LAS VEGAS, NEVADA

Mob Museum (Photo: Atlas Obscura / Rachel James.)

Mob Museum (Photo: Atlas Obscura / Rachel James.)The snare that brought the bloody feud between two Chicago mobster titans to a head turned out to be quite simple. Step one: Invite the North Side Gang out in their Valentine’s Day best. Step two: Line them up against a wall like sitting ducks. Step three: Pull the trigger and hold it down.

The 1929 massacre of seven members of the North Side Gang horrified the nation with its brutality and careful execution. Bugs Moran of the North Side Gang and Al Capone of the South Side Italians had been trying to bump each other off for years, fighting over turf, dog tracks, and hooch, and the community was in constant fear of getting caught in the crossfire. It seemed both men were untouchable, but a failed assassination attempt by Bugs on a Capone mobster named Jack “Machine Gun” McGurn proved to be a fatal mistake, one that in retrospect seems obvious—if you shoot at someone named “Machine Gun” you’d better make sure he’s dead.

The details are disputed by historians and gangster enthusiasts, but the essential story is that seven men, dressed to the nines, entered the warehouse to do some business. The next thing they knew, a police car had appeared and two coppers had pulled their weapons and told the gangsters to face the brick wall, with their hands up. The men, thinking this was a routine shakedown by the fuzz, did as they were told and turned their backs to the gunmen, hands in the air. Like fish in a barrel, a sizable chunk of the North Side gang was then mowed down by four (some say five) gunmen when the “police” opened fire, and were joined by their plain-clothed co-conspirators. After slaughtering their enemies in an extravagant volley of bullets, the “police” walked their fellow gunmen out to the stolen patrol car at gunpoint, leaving gawking citizens with the impression that two crooks had just been taken off of the streets by the boys in blue, completely unaware of the carnage left behind.

What appeared to be a seamless plan went off without a hitch, except for one thing – Bugs was not among the men now piled in a bloody heap at the foot of the brick wall. Running late, Bugs had seen the police car and turned back, assuming a sting was going down. The lookout who had given the go-ahead had confused one of Bugs’ men, Albert Weinshank, for the mob boss, who shared a similar build. Today the wall itself can be seen in the Mob Museum in Las Vegas, Nevada

Joe Gallo vs. The Colombo Family - Site of Joe Gallo’s 1950 Headquarters

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

Gallo HQ (Photo: Unknown / Wikipedia)

Gallo HQ (Photo: Unknown / Wikipedia)When the docks are full of opportunities to make a buck, why let one mob boss reap all the riches?

This was the question asked by a group of Gallo brothers and local thugs working for Brooklyn’s waterfront crime circuit in the 1960’s. As the Gallo brothers ambitions grew, they tried to strike out on their own to terrible effect. It was in his house in Red Hook, Brooklyn that Joe Gallo lived with his pet lion and a stockpile of arms, and it was from here that he lead his brothers in an all-out war against mobster Joe Profaci.

After working for Profaci’s rackets for several years, Gallo’s gang elected to kidnap his sister to show they were serious about breaking away from his influence to start their own extortion operation. This was the first of many plans by the brazen Gallo lot which backfired. To retaliate for the kidnapping of his sister, Profaci’s thugs attempted to strangle Larry Gallo and Joseph Magnasco of the Gallo gang was shot and killed in the encounter. The next year saw 12 more casualties, dozens more attempted assassinations and well over 100 arrests in the first open gang war in Brooklyn since the famous 1931 Castellammarese War.

The war ground to a halt in 1961 when Joe Gallo was convicted of conspiracy and extortion. After his release, he was gunned down in a Little Italy restaurant while celebrating his 43rd birthday. Though the local Catholic church refused to perform an official service, Gallo was laid to rest in Green-wood cemetery. A sort of mafia folk hero, Bob Dylan’s song “Joey” was inspired by Joseph Gallo’s death. ”I never considered him a gangster. I always considered him some kind of hero…An underdog fighting against the elements,” Dylan once said of him.

In 1975, while trying to replace a sewer line, a cave-in killed a city worker and forced the city to demolish 33 buildings, including Joe Gallo’s old haunt. Today, what remains on the site is simply the memory of a young, ruthless and ultimately foolhardy mafioso.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook