The Feminist Architect Who Tried to Liberate Kitchens From Houses

In the early 20th century, Alice Constance Austin dreamed of collective housekeeping.

Some of the women dreaming of a cooperative life at the Llano Del Rio socialist commune. (Photo: Walter Millsap and Meyer Elkins)

In most contemporary home design, the kitchen is designed to be a central gathering space for families to eat, cook, and socialize. At the turn of the 20th century, during the emergence of the first modern American suburbs, the middle-class kitchen transformed from a servant’s workplace hidden from view to a housewife’s domain—a transition further encouraged by the emerging advertising industry intent on selling newly mass-produced items like refrigerators and electricity.

But what if there was no open concept kitchen, or even a kitchen at all? For some people, that idea sounds ludicrous. For feminist architect Alice Constance Austin, it was revolutionary.

Alice Constance Austin showing models to Llano del Rio colonists in 1916. (Photo: Public Domain)

Austin was a self-taught architect from California who is primarily known for her kitchen-less home designs for the Llano Del Rio socialist commune in the mid-1910s. In 1914, Los Angeles-area lawyer Job Harriman invited local residents (provided they were white, union-affiliated, and socialist) to join his utopian society of likeminded people in the Antelope Valley.

Austin was brought on in 1915 to help design the living quarters for 900 new residents, combining Harriman’s socialist ideas with her own feminist ones to build her vision for a town without housework.

A kitchen in use, c1897. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-90461)

To create the kitchenless house, Austin looked to technological developments in electricity, automation and railways for her designs. She didn’t envision a place where nobody cooked; instead, kitchens would become centralized (as would laundry), and treated as part of the larger infrastructure of the community. The houses would be arranged in rows, with paths in between for automobiles and pedestrians. In The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities, urban historian and architecture professor Dolores Hayden writes that Austin planned for food preparation that “would arrive from the central kitchens to be eaten in the dining patio” of each home she designed. Dirty dishes “were then to be returned to the central kitchen for washing by machine.” She drew up plans for houses with a living room at one end and bedrooms at the other, with a large dining patio in between. She also included built-in furniture in her plans for each dwelling’s rooms, to reduce hours spent dusting and sweeping.

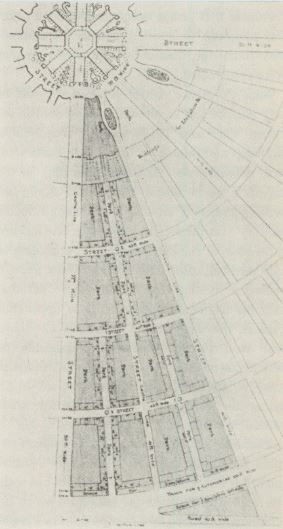

One of Austin’s plans for the commune, c. 1916. (Photo: Public Domain)

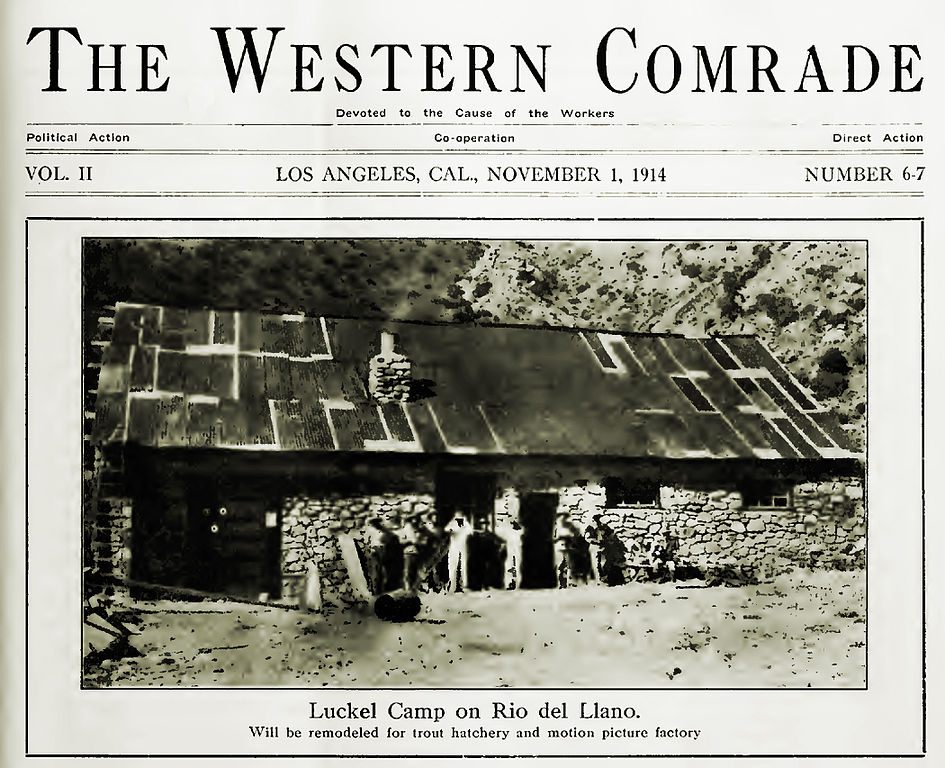

Hayden writes that Austin’s plans relied heavily on an “underground network of [rail] tunnels” that could shuttle deliveries from the center of the city to the residential areas. Surrounding each house were shrubs, trees, and flowers, because, as she wrote in the community’s Western Comrade newspaper (owned by Harriman) in October 1916, the socialist city “should be beautiful.”

A 1914 issue of The Western Comrade, “devoted to the cause of the workers”, reporting on Llano del Rio. (Photo: Public Domain)

It was a vast vision—and it wasn’t hers alone. In exporting these household tasks from the domestic space of the home, Austin hoped to eliminate “the thankless and unending drudgery of an inconceivably stupid and inefficient system,” as she later wrote in her 1935 book, The Next Step—How to Plan for Beauty, Comfort, and Peace with Great Savings Effected by the Reduction of Waste. Images of a kitchenless future were already part of feminism and popular culture at the time. Edward Bellamy published a popular science fiction novel called Looking Backwards in 1888, which envisioned America in the year 2000 as a socialist utopia with public kitchens and rapid delivery services. Ten years later, feminist activist and author Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote Women and Economics, connecting the fight for women’s rights to the issue of domestic liberation for middle-class white women. In Women and Economics, she wrote:

“Take the kitchens out of the houses, and you leave rooms which are open to any form of arrangement and extension; and the occupancy of them does not mean ‘housekeeping.’ In such living, personal character and taste would flower as never before… The individual will learn to feel himself an integral part of the social structure, in close, direct, permanent connection with the needs and uses of society.”

By the time Austin was working on the Llano Del Rio plans, community kitchens and cooperative housework projects were popping up around the country, promoted by radical feminists as an effective cure for housewife fatigue. Austin took these ideas of empowerment through outsourcing a step further than other feminist activists, imagining a complete redesign of private and public spaces in the name of furthering equality for women.

Members of Llano del Rio outside a machine shop in the colony, 1914. (Photo: Public Domain)

Ultimately, the kitchenless house was never built. In Utopianism and Radicalism in a Reforming America, Francis Robert Shor writes that, due to a lack of capital and water, as well as American involvement in the First World War in 1917, the Llano Del Rio commune had all but disappeared in California by 1918. Austin’s dream of a kitchenless socialist city died with it, but she continued to write and speak about the possibilities of the design into the 1920s and 1930s, focusing on technology and the role it would play in eliminating housework for every citizen.

The ruins of Llano del Rio in California. (Photo: Konrad Summers/CC BY-SA 2.0)

While Austin’s design for the kitchenless house was not the first of its kind, Hayden writes in the academic journal Signs in 1978 that Austin was the first architect to envision an end to domestic drudgery on such a large scale, and the first to expand the idea outside the confines of an individual dwelling and into an entire community. Maybe, as feminism moves firmly to mainstream pop culture in 21rst century America, we may yet see it show up in home design.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook