The First Global Urban Planning Conference Was Mostly About Manure

The threat was real. And stinky.

Electric streetcars eventually began to replace horse-drawn cars in the early 20th century. (Photo: Brown Brothers/Public Domain)

Electric streetcars eventually began to replace horse-drawn cars in the early 20th century. (Photo: Brown Brothers/Public Domain)

The sticking point at the world’s first international urban planning conference was a load of crap.

When delegates from around the globe gathered in 1898 to hammer out a solution to one of the greatest problems facing their cities, whose consequences they could no longer ignore, they weren’t talking about infrastructure challenges, a shortage of resources, or even crime.

The problem was horses. And their copious poop.

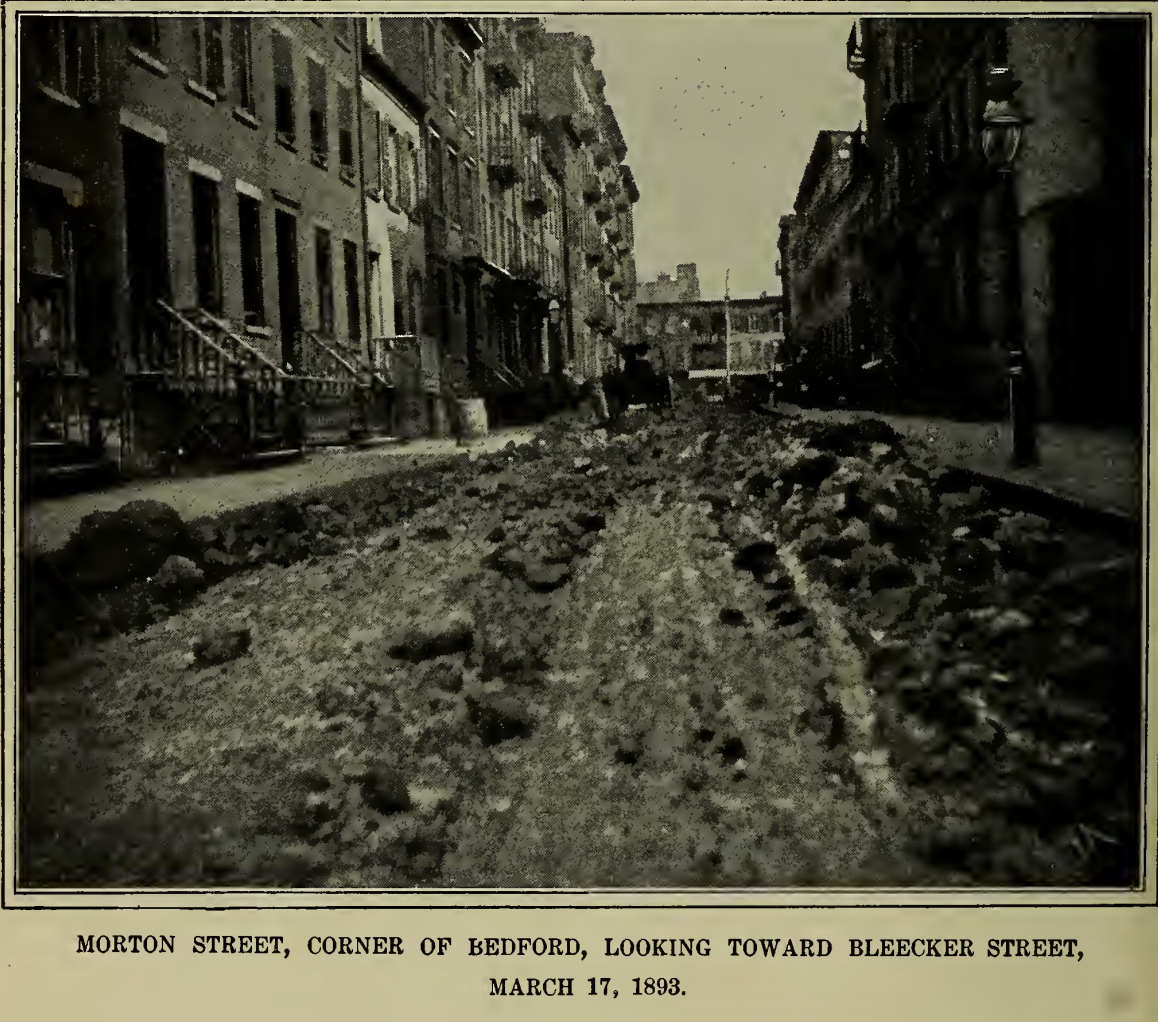

A view of a muddy and manure-covered New York City street in 1893, found in an 1898 book about street cleaning. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

A view of a muddy and manure-covered New York City street in 1893, found in an 1898 book about street cleaning. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

The manure issue had become particularly acute as horse populations swelled in rapidly growing urban centers. It was considered such a looming threat to cities that an 1894 article in the Times of London estimated that within 50 years, dung piles would rise nine feet high.

A similarly concerning New York City prediction argued that by 1930 manure would reach third-story windows. Moreover, 19th-century New York was already unsettlingly unsanitary, with whole swathes of the city dominated by “a loathsome train of dependent nuisances” like slaughterhouses, facilities for fat melting and gut-cleaning, and “manure heaps in summer” that stretched across entire blocks.

But after three days of brainstorming and debate that went nowhere, attendees of the conference, frustrated and resigned, called it quits on what had been planned as a 10-day affair. Participants had hoped to hammer out a solution to the horse problem and its smelly attendant consequences, but instead, seeing no way out of the morass, they disbanded and went home.

Horses were once vital to the operation of trams, like this one in London from the end of the 19th century. (Photo: Oxyman/Public Domain)

Horses were once vital to the operation of trams, like this one in London from the end of the 19th century. (Photo: Oxyman/Public Domain) After all, how could they come up with a substitute for an animal that had served humans for thousands of years? Horses were essential to the transportation of people and cargo, as well as a source of prestige and power for militaries.

But crammed together in such tight spaces—the human density of New York City rose over the 19th century from just below 40,000 people per square mile to above 90,000—the beasts became less of an object of convenience and more of a debilitating nuisance.

The crowded Mulberry Street in New York City around 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZC4-4637)

The crowded Mulberry Street in New York City around 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZC4-4637)

At its peak, New York had an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 equine inhabitants. Each of those horses produced anywhere from 15 to 30 pounds of manure per day, coupled with around a quart of urine that ended up either in their stables or anywhere along their street routes.

And as equestrian enthusiasts are well aware, horse poop begets flies. Lots of flies. One estimate cited in Access Magazine claimed that horse manure was the hatching ground for three billion flies daily throughout the United States, flies that spread disease rapidly through dense human populations.

A view of a street in Riverside, California, with horse droppings littering the roadway. (Photo: CC Pierce/Public Domain)

A view of a street in Riverside, California, with horse droppings littering the roadway. (Photo: CC Pierce/Public Domain)By the end of the 19th century, once-vacant lots around New York City housed manure piles that stretched dozens of feet—often between 40 and 60—into the sky. The problem of horse manure had quite literally become larger than life.

And the problem comprised more than just excrement. When a horse, worked to the bone, plopped over dead, the city then had a rotting carcass to address, not to mention the flies and road congestion that accompanied it.

According to Raymond A. Mohl’s book The Making of Urban America, by 1866 the city’s long Broadway had become littered with “dead horses and vehicular entanglements,” and in 1880 alone, New York City removed around 15,000 horse carcasses from its streets. As late as 1912, Chicago carted away nearly 10,000 carcasses.

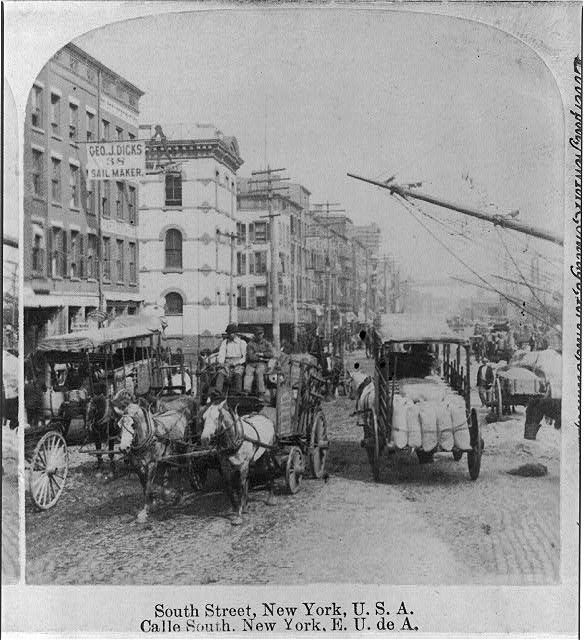

A view of New York City’s South Street crowded with horses and carriages. (Photo: Library of Congress/Public Domain)

A view of New York City’s South Street crowded with horses and carriages. (Photo: Library of Congress/Public Domain)

Some respite came in the late 1880s and 1890s with the introduction of the cable car and electric trolley car to American cities, but it wasn’t until the private automobile became available in the early 20th century that horses began to be phased out of daily life. As prices for hay, oats, and land rose, and fears of horse pollution became more urgent, the masses began to adopt the fledgling technology.

By 1912, the number of cars on New York City’s roads had surpassed the number of horses. Buyers found cars to be cheaper to own and operate and much more efficient—not to mention more sanitary. The once-essential horse came under fire from magazines like Harper’s Weekly and Scientific American, which praised the automobile for its economic sustainability and ability to reduce traffic.

And so, by some miracle, the problem that had plagued planners and had sent them into a panic began to disappear. Had they known at the first international planning conference that their most pressing challenge would essentially resolve itself in years to come, perhaps they wouldn’t have wasted so much effort arguing about waste.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook